A History of the World in 100 Objects (57 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

For medieval Christians the only hope of escaping the torments of hell lay in the redeeming blood that Christ had shed. So, at the very centre of the reliquary is Christ, showing us his wounds, and just below him is one of the long, needle-like thorns that caused that holy blood to flow.

Ista est una spinea corone Domini nostri Ihesu Christi

, reads the enamel label: ‘This is a thorn from the crown of our lord Jesus Christ’.

The Roman Catholic Bishop of Leeds, the Right Reverend Arthur Roche, emphasizes its significance:

It certainly becomes a focus for the reflection on deeper things as to the cost of suffering. Especially when you think that if that thorn is authentic, then it was actually piercing the head of Christ during the course of his suffering and his crucifixion, and in some sense connects our suffering on this earth to his suffering for us; the focus gives us a strength to endure the things that we are presently going through.

It is impossible to exaggerate how powerfully this object would affect any believer kneeling in front of it. The blood drawn by this worthless thorn will save immortal souls, and so nothing earthly can be too precious for it, neither the sapphire it stands on, nor the rock crystal that protects it, nor the rubies and the pearls that frame it. This is a sermon in gold and jewels, an aid to intense contemplation and a source of the deepest comfort.

There is no way now of proving that this was a thorn that actually pierced the head of Christ, but we can say with confidence that it is a type of buckthorn that still grows around Jerusalem. The first mention of the Crown of Thorns as a relic is in Jerusalem around 400. It was later taken from the Holy Land to Constantinople, the Christian capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, where it was kept and venerated for centuries. But shortly after 1200 the impecunious emperor pawned the crown to the Venetians for a mammoth sum. This shocked his cousin, the crusader king of France, Louis IX, but it also gave him an opportunity. He paid off the emperor’s debt and redeemed the relic. So, although Louis as a crusader failed to conquer the Holy Land, the site of Christ’s suffering, he did acquire the Crown of Thorns. So great was its power in medieval people’s eyes that through it Louis was linked directly to Christ himself. To house his incomparable relic Louis built not just a reliquary, but a whole church. He called it his Holy Chapel – the Sainte-Chapelle.

The stained-glass windows of the Sainte-Chapelle leave us in no doubt that Paris and the kingdom of France are to be permanently transformed by the arrival of the Crown of Thorns. Louis, who became St Louis when canonized in 1297, is shown paired with Solomon; the Sainte-Chapelle is his temple and Paris has become Jerusalem. When the crown arrived, it was described as being on deposit with the king of France until the Day of Judgement, when Christ would return to collect it and the kingdom of France would become the kingdom of Heaven. When this chapel was completed and dedicated in 1248, the archbishop proclaimed: ‘Just as the Lord Jesus Christ chose the Holy Land for the display of the mysteries of his redemption, so he has specially chosen our France for the more devoted veneration of the triumph of his Passion.’ The Crown of Thorns has played a long and fascinating part in the international politics of piety – it allowed St Louis to claim for France a unique status among the kingdoms of Europe, and every French ruler since St Louis has wanted to follow his example.

The historian Sister Benedicta Ward sees this as something more than a religious quest:

To have a relic particularly connected with the passion of Christ was the best thing you could have. But there were also relics of the saints, particularly the martyrs. I think they provoked a lot of envy, especially the French collections. The rivalry in England was intense: ‘We want to have a better relic than they have because we are a better nation than they are.’ They are subject to all kinds of external influences. Like everything else it can be part of commerce. Politics, commerce, exchange – this is certainly all round the relics.

In the complex economy of political influence, a thorn from the crown became the ultimate French royal gift. In the late fourteenth century one came into the possession of a powerful French prince, Jean, duc de Berry, and we can be absolutely confident that the reliquary in the British Museum belonged to him. It has his coat of arms enamelled on to it, and it also sums up many of his preoccupations: he commissioned some of the greatest religious art of the period and he was a passionate collector of relics. He had what were claimed to be the marriage ring of the Virgin, a cup used at the wedding at Cana, a fragment of the Burning Bush and a complete body of one of the holy innocents, the children murdered by Herod. He was also an enthusiastic builder of castles, and so, appropriately, the base of our reliquary is a castle made out of solid gold. This Holy Thorn Reliquary is certainly one of the supreme achievements of medieval European metalwork, but sadly there is no way of knowing if it was the greatest artefact in Jean de Berry’s collection. The bulk of his goldsmiths’ work was broken up and melted down within months of his death, when the English occupied Paris after the Battle of Agincourt in 1415. The survival of this reliquary means that he must have given it away before he died.

We are not sure who he gave it to, but by 1544 it was in the treasury of the Habsburg emperors in Vienna, and from there its secularization begins – the gold, enamel and jewels becoming far more valuable and interesting than the humble thorn that they house. In the 1860s it was sent for restoration to a dishonest antique dealer, who, instead of carrying out the repairs, created a forgery which he sent back in its place to the imperial treasury, keeping the original himself. Eventually the genuine reliquary was bought by the head of the Vienna branch of the Rothschild bank, and donated to the British Museum by Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild in 1898 as part of the Waddesdon Bequest, which now occupies the whole of a small gallery at the Museum.

You could almost say the Holy Thorn Reliquary is itself a single-object museum, if an incomparably lavish one – one exhibit mounted on sapphire, displayed behind rock crystal and labelled on enamel. But its purpose is the same as that of any museum: to provide a worthy setting for a great thing. We can’t know exactly how visitors approach objects on display in the British Museum, but many still use the Holy Thorn Reliquary for its original devotional purpose of contemplation and prayer.

Solomon and the Queen of Sheba in the central diamond of a window in the Sainte-Chapelle

The veneration of the Crown of Thorns itself remains very much alive. Napoleon decided that it should be housed permanently in Notre-Dame, and there, on the first Friday of every month, the whole Crown of Thorns, from which our one thorn was taken more than 600 years ago, is still shown to crowds of faithful worshippers.

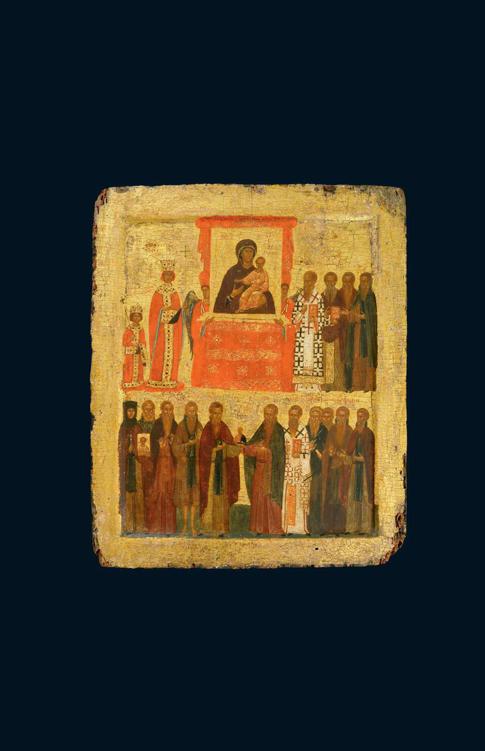

Icon of the Triumph of Orthodoxy

AD

1350–1400

What does a great empire do when faced with imminent invasion and destruction? It can rearm at home and seek allies abroad; but more cunningly it can revisit its history to forge a myth that will unite the people and carry them through to victory, a myth that will demonstrate to everyone that their country has been specially chosen by history to uphold justice and righteousness. It is what the French did in 1914 and the British in 1940. In such circumstances, history reimagined can be a very powerful weapon. When the Christian Byzantine Empire faced obliteration at the hands of the Ottoman Turks around 1400, it too turned to its past, found an event that proclaimed its unique and divinely ordained purpose, and turned it into a national myth. The Byzantines promoted their myth in the most public medium at their disposal: they established a new religious feast day and commissioned a religious icon to mark it.

For the Byzantine Empire it had never been more important to seek divine help. The successor to the Roman Empire, the defender of Orthodox Christianity, and for centuries the superpower of the Middle East, the empire had shrunk to a shadow of its former greatness. By 1370 it was no more than a minor state that extended barely beyond the walls of Constantinople, modern Istanbul. All its provinces had been lost, most of them conquered by the Muslim Ottoman Turks who now threatened the city on every side; even the survival of Orthodox Christianity itself seemed to be in question.

There was little hope of military help from further away. Two brave attempts from western Europe to send reinforcements had been catastrophically defeated in the Balkans. On several occasions the emperor himself travelled from Constantinople to the kingdoms of the West – even as far as London – to plead for money and soldiers, but to no avail. By 1370 it was clear that there was going to be no earthly salvation. Only God could help in a situation so desperate. These were the bleak circumstances in which the icon of the Triumph of Orthodoxy was painted. It shows the world of the Byzantine Empire not as it actually was, but as it needed to be if God was going to protect it.

‘

Icon’ is simply the Greek word for picture, and this picture is about 40 centimetres (16 inches) high, almost exactly the same shape as the screen of a laptop computer. It is painted on a wooden panel, the figures in black and red, the background shining gold. In the centre, at the top, we see two angels holding up a picture for veneration – the most famous of all Orthodox icons and one particularly connected to Constantinople. Known as the Hodegetria, it shows the Virgin Mary with the Christ Child in her arms. The Hodegetria is being venerated by a host of saints, by the head of the Orthodox Church – the Patriarch – and by the imperial family. Between them, they represent all Constantinople, temporal and spiritual. This icon is a picture about the use of a picture, and it is a celebration of the central role that icons play in the Orthodox Church.

This is how Diarmaid MacCulloch, Professor of the History of the Church at Oxford University, describes the function of an icon:

The icon is like a pair of spectacles which you put on to see heaven. You’re drawn through this picture into heaven because Orthodox Christianity believes very strongly that you and I can meet the godhead, that we can almost become like gods. It’s that extraordinary, frightening statement that Western Christianity is very shy of.

The painting of icons was primarily a spiritual rather than an artistic activity, and it was governed by strict guidelines. The particular artist is not important: the key is motivation and methodology. This is an aspect of icons that fascinates the American artist Bill Viola, who quotes from a medieval document:

This is a short text from the Middle Ages called

The Rules for the Icon Painter

.Number one, before starting work make the sign of the cross, pray in silence and pardon your enemies. Two, work with care on every detail of your icon as if you were working in front of the Lord himself. Three, during work, pray in order … Nine, never forget the joy of spreading icons in the world, the joy of the work of icon painting, the joy of giving the Saint the possibility to shine through his icon, the joy of being in union with a Saint whose face you are painting.

What exactly is the Triumph of Orthodoxy as shown in our painting? To find out we have to go back another 700 years. Given the centrality of icons in Orthodox worship and the fervour with which they are described, it comes as a shock to discover that for 150 years they were not only forbidden in Orthodox churches but actively sought out and smashed. Around the year 700, the Byzantine Empire nearly succumbed to the armies of a new faith, Islam. In striking distinction to Christianity, Islam forbade the use of religious images – and it was clearly an alarmingly successful faith. Had Christianity taken a wrong turn? Was it breaking the Second Commandment – the one that forbids the making of graven images? Was the state church on the wrong track? Was that why the military campaigns were going so badly? Suddenly, the use of images in church seemed to raise a huge and fundamental question, as Diarmaid MacCulloch explains: