A History of the World in 100 Objects (63 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

Inca tyranny is at our gate … If we yield to the Inca, we shall be obliged to give up our former freedom, our best land, our most beautiful women and girls, our customs, our laws … We shall become for all time this tyrant’s vassals and servitors.

The Inca hold on many of its provinces was fragile. Continuous rebellions tell of potential weakness, which turned out to be crucial when Pizarro returned to conquer Peru in 1532. Some of the local elites immediately seized the opportunity to ally with the incomers and throw off the Inca yoke.

As well as being joined by a growing number of rebels, the Spanish had swords, armour and guns, none of which the Incas possessed – and crucially they also had horses. The Inca had never before seen men on the backs of animals, nor had they seen the speed and agility with which this combination of man and beast could move. The Inca llamas must have suddenly looked hopelessly delicate and slow. It was all over fairly quickly – a mere couple of hundred Spaniards massacred the Inca army, captured their emperor, installed a puppet ruler and seized and melted down their gold treasures. Our little llama is one of the rare survivors.

The Spanish had come to Peru lured by tales of enormous quantities of gold. But they discovered instead the richest silver mines in the world and began to mint the coins that would power the world’s first global currency. The Inca measured the wealth of their empire in llamas. The Spanish would measure theirs, as we shall see in

Chapter 80

, in silver pieces of eight.

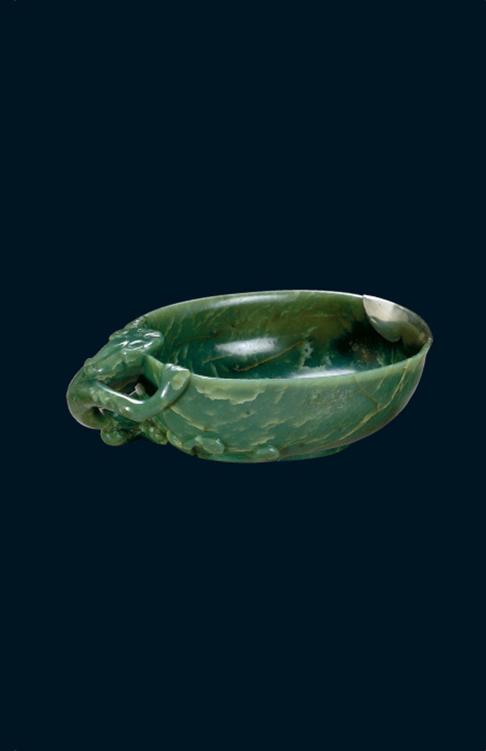

Jade Dragon Cup

AD

1417–1449

We’ll lead you to the stately tent of war,

Where you shall hear the Scythian Tamburlaine

Threatening the world with high astounding terms,

And scourging kingdoms with his conquering sword.

In these words Christopher Marlowe fixed for ever the European image of Tamburlaine, still a legendary force in Elizabethan England. A couple of hundred years earlier, by 1400, the real Tamerlane had become the ruler of all the Mongol lands except China. The heart of his empire was the region we now know as the ‘stans’ – Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan. That huge area in central Asia has always had a fluctuating history, where empires build, crumble and fade – until another empire rises and the cycle begins again. It is a region that has inevitably had two faces – one looking towards China in the east and the other towards Turkey and Iran in the west. Samarkand, Tamerlane’s capital, was a major city on the great Silk Road that linked these two worlds. Much of this complex cultural and religious history is embodied in this small jade cup, which belonged to Tamerlane’s astronomer grandson, Ulugh Beg.

The surface of the Moon is dimpled with hundreds of craters. For the Moon-watcher they add interest and texture, but their names also provide another kind of pleasure: they form a kind of dictionary of great scientists. There are craters honouring Halley, Galileo and Copernicus and many more astronomers – and among them is Ulugh Beg, who lived in central Asia at the start of the fifteenth century. Ulugh Beg built a great observatory in Samarkand, in modern Uzbekistan, and compiled a famous catalogue of just under a thousand stars, which became a standard work of reference in both Asia and Europe, and was translated into Latin in Oxford in the seventeenth century – it was this which earned him the honour of that crater on the Moon. He was also briefly the ruler of one of the world’s great powers – the Timurid Empire, which at its height ruled not only central Asia, but also Iran and Afghanistan, as well as parts of Iraq, Pakistan and India. The Timurid Empire had been founded by the redoubtable Tamerlane in the years around 1400. The name of his grandson, the astronomer prince Ulugh Beg, is incised on the cup pictured here.

The Uzbek writer Hamid Ismailov says:

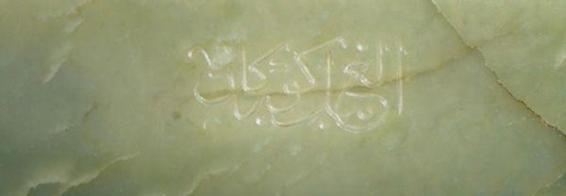

It is extremely exciting that this object belonged to Ulugh Beg, because I can see here in Arabic

Ulugh Beg Kuragan

and imagine that it served Ulugh Beg while he was looking at the stars. It’s magnificent.

Ulugh Beg’s cup is oval, just over 6 centimetres (2½ inches) high and 20 centimetres (7 inches) long – more a small bowl than a cup – and made from a superbly grained olive-green jade with natural cloud-like markings drifting across the glossy stone. It is very beautiful, but jade was valued in central Asia not just for its beauty, but also for its powers of protection: jade would keep you safe against lightning and earthquakes and – especially important in a cup – against poison. Poison placed in a jade cup, so it was said, would result in the vessel splitting. The owner of this cup could drink without fear.

The cup’s handle is a splendid Chinese dragon. It has its back feet firmly planted on the underside of the bowl, while its mouth and webbed front feet cling to the edge at the top. It peeps over the rim of the bowl, so you can put your finger through the space left by its curving body. It’s a sensuous, intimate experience.

The style of the handle may be Chinese, but the inscription – Ulugh Beg Kuragan – carved into the cup is in Arabic script. Kuragan is a title that literally means ‘royal son-in-law’, but it was used by Tamerlane and later by Ulugh Beg. They had both married princesses of the house of Genghis Khan, and by calling themselves sons-in-law they declared themselves the heirs to the universal sovereignty of Genghis Khan’s Mongol Empire.

The Arabic inscription reading ‘Ulugh Beg Kuragan’

A later repair carries a Turkish inscription: ‘There is no limit to the beneficence of God ‘

So, the cup was probably made in Samarkand, with a handle showing connections east to China, and an inscription looking west to the Islamic world. The Arabic inscription reminds us that this new Timurid Empire created by Tamerlane was energetically Muslim. This is the time of the building of the great mosques of Bukhara and Samarkand, Tashkent and Herat, conceived and executed on a monumental scale, a central Asian equivalent of the European Renaissance.

From about 1410 Ulugh Beg governed Samarkand for his father, and there he built the observatory in which he revised and corrected the astronomical computations of the ancient Greek Ptolemy – the same fusion of Classical Greek and Arab scholarship that we saw in the medieval Hebrew Astrolabe (see

Chapter 62

). But this central Asian Renaissance prince didn’t take after his military, empire-building grandfather Tamerlane. The historian Beatrice Forbes Manz sums him up:

He was a very poor commander and probably not a great governor in certain ways. He was, however, an excellent cultural patron, famous especially for his patronage of mathematics and astronomy. These were his real passions, much more I think than government or military campaigning. He also had a passion for jade, so it’s not surprising to find that cup in his possession, and he had a fairly high-living court, looser morally than his father’s. Ulugh Beg was pious, he knew the Qur’an by heart, but he, like many rulers, took a certain amount of licence. So there was a lot of drinking, for instance, at his court.

An envoy from Ming China who visited Samarkand around 1415 was taken aback at the free-wheeling manners of the Timurid capital, which still smacked of the easy-going informality of a semi-nomadic society. It was an odd city, designed to accommodate both modern buildings and traditional tents, the yurts that the Timurids had brought with them from the steppes. For the rarefied Chinese visitor, Samarkand was the Wild West:

They have no principles or propriety. When inferiors meet superiors, they come forward, shake hands, and that is all! When women go out, they ride horses and mules. If they meet someone on the road, they chat, laugh and fool around with no sense of shame. Moreover they utter lewd words when conversing. The men are even more despicable.

Perhaps it is not surprising that the Timurid Empire, bound together only by personal loyalties, didn’t survive long. It was run by people more at home on the steppes than in a government office. There was no established habit of orderly central power and barely any working bureaucracy. The death of every ruler brought chaos. Ulugh Beg’s father had struggled to rebuild the Timurid Empire, but after his death in 1447 Ulugh Beg would reign for only two years before he lost control. He tried hard to use the reputation of Tamerlane to bolster his authority, burying his illustrious grandfather under a monument made of rare black jade, inscribed in Arabic for all to see: ‘When I rise, the world will tremble’. He must have longed for the return of a power that he knew he himself could never match. The earth was unlikely to tremble at Ulugh Beg. Hamid Ismailov sees a poetic, metaphorical meaning in his green jade cup:

The symbolism of this cup is seen throughout the whole region as a sort of destiny of a person. When we say ‘the cup is filled’, so destiny is fulfilled. And so, for example, Babur, who was a great poet as well as the nephew of Ulugh Beg, says in one of his poems that troops of sadness are countless, and the only way to deal with them is bringing thicker wine and keeping a cup as a shield. That is the symbolism of the cup – it’s a shield, a metaphysical shield against the troops of sadness.

But it was a shield that failed, and towards the end of his life, the troops of sadness came crowding in on Ulugh Beg. His two-year rule of the empire was as disastrous as it was brief. Very unmetaphorical troops invaded Samarkand, and in 1449 he was defeated and captured by his own eldest son, handed over to a slave and decapitated. But Ulugh Beg was not forgotten. His great-nephew Babur, who became the first Mughal emperor of India, honoured him by interring his remains in the black jade monument alongside those of the great Tamerlane.

By that time the Timurid Empire was over. Once again central Asia fragmented and became the theatre of competing influences, among them the great new power in the West, the Ottoman Empire. That later development, too, is recorded in our cup. At some point, presumably long after Ulugh Beg’s death, the precious jade cup must have been dropped, because it is badly cracked at one end. But the crack has been covered up by a repair in silver, and on the silver is an inscription. It was probably engraved in the seventeenth or eighteenth century, 300 years after its owner’s execution. The inscription is in Ottoman Turkish, so the cup by then had probably found its way to Istanbul. It reads, ‘There is no limit to the beneficence of God’.