A History of the World in 100 Objects (45 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

On the carving King Shield Jaguar and his wife are both magnificently dressed, their spectacular headdresses probably made of jade and shell mosaic and decorated with the shimmering green feathers of the quetzal bird. On top of the king’s headdress you can see the shrunken head of a past sacrificial victim, possibly a defeated enemy leader. On his breast he wears an ornament in the shape of the sun god, his sandals are of spotted jaguar pelt, and at his knees there are bands of jade. His wife has particularly elaborate necklaces and bracelets.

This image is one of three found in the temple, each one positioned above an entrance. Together they make it clear that the act of pulling thorns through the tongue was not just to make the Queen’s blood flow as an offering but was deliberately intended to create intense pain – pain which, after due ritual preparation, would send her into a visionary trance.

Sado-masochism, on the whole, receives a bad press. Most of us take quite a lot of trouble to avoid pain, and wilful ‘self-harm’ suggests an unstable psychological condition. But around the world there have always been believers who see self-inflicted pain as a route to transcendental experience. To the average twenty-first-century citizen, and certainly to me, this willed suffering has about it something deeply shocking.

For the queen to inflict such agony on herself was a great act of piety – it was her pain that summoned and propitiated the kingdom’s gods, and that ultimately made possible the king’s success. The psychotherapist and writer on women’s psychology, Dr Susie Orbach:

If you can create a feeling of pain in the body and you survive it, you can move into a state of, not quite ecstasy, but out-of-the-ordinariness, a sense that you can transcend, you can do something rather special.

What I find interesting about this image, which is quite startlingly horrific, is how visible the woman’s pain is. I think that, in the present day, we’ve come to hide our pain. We have jokes about our capacity for pain but we don’t really show it.

What we see here is something that women can understand and can reflect upon, although it’s very exaggerated; the kind of relation to self and to a husband that a woman often makes – or to her children. And it’s not that men are extracting them. It’s that women experience their sense of self by doing these things, by enacting them. They give them a sense of their own identity. And I’m sure that was true for her.

The next lintel in the series shows us the consequence of the queen’s self-mortification. The ritual blood-letting and the pain have combined to transform Lady K’abal Xook’s consciousness, and they enable her to see, rising from the offering bowl that holds her blood, a vision of a sacred serpent. From the mouth of the snake a warrior brandishing a spear appears – the founding ancestor of the Yaxchilan royal dynasty, establishing the king’s connection with his ancestors and therefore his right to rule.

For the Maya, blood-letting was an ancient tradition, and it marked

all the major points of Maya life – especially the path to royal and sacred power. In the sixteenth century, 800 years after this lintel was carved, and long after the Maya civilization had collapsed, the Spanish encountered similar blood-letting rites that still survived, as the first Catholic bishop of Yucatán reported:

They offered sacrifices of their own blood, sometimes cutting themselves around in pieces and they left them in this way as a sign. Sometimes they scarified certain parts of their bodies, at others they pierced their tongues in a slanting direction from side to side and passed bits of straw through the holes with horrible suffering; others slit the superfluous part of the virile member leaving it as they did their ears.

The unusual thing about our sculpture is that it shows a woman playing the principal role in the ritual. Lady K’abal Xook came from a powerful local lineage in Yaxchilan, and by taking her as a wife the king was allying two powerful families. This particular lintel is an extraordinary example of the kinds of rights and ceremonies that a queen would engage in. We don’t have a series like it from any other Maya city.

K’abal Xook’s husband, Shield Jaguar, had an immensely long reign for the age, but within a few decades of the deaths of the couple, all the great cities of the Maya were in chaos. On the later Maya monuments, warfare is the dominant image, and the last monuments date to around

AD

900. An ancient political system that had lasted for more than a thousand years had disintegrated, and a landscape where millions had lived seems to have become desolate. Why this should have happened remains unclear.

Environmental factors are a popular explanation – there is some evidence of a prolonged drought, and, given the density of the population, the decline in resources a drought would cause could well have been catastrophic. But the Maya people did not vanish. Mayan settlements continued in several areas, and a functioning Mayan society lasted right up to the Spanish Conquest. Today there are about six million Mayans, and their sense of heritage is strong. New roads now open up access to the formerly ‘lost’ cities – Yaxchilan, where our sculpture came from, used to be accessible only by light plane or a river trip across hundreds of miles, but since the 1990s it is just an hour’s boat ride from the nearest town and a big draw for tourists.

A vision of a sacred serpent and warrior ancestor rises from Lady K’abal Xook’s offering bowl

There was a Maya uprising as recently as 1994, when the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, as they called themselves, declared war on the Mexican state. Their independence movement profoundly shook modern Mexico. ‘We are in the new “Time of the Mayas”,’ a local play proclaimed, as statues of the Spanish conquistadors were toppled and beaten into rubble. Today, the Maya are using their past to renegotiate their identity and seeking to restore their monuments and their language to a central role in national life.

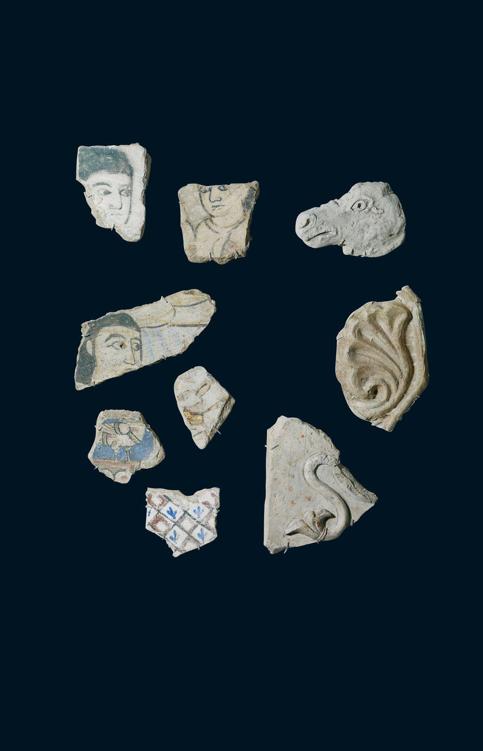

Harem Wall-painting Fragments

800–900

AD

The world of the

Arabian Nights

– the 1,001 tales supposedly told by the beautiful Scheherazade to stop the king from killing her – transports us to the Middle East of twelve centuries ago:

The girls sat around me, and when night came, five of them rose and set up a banquet with plenty of nuts and fragrant herbs. Then they brought the wine vessels and we sat to drink. With the girls sitting all around me, some singing, some playing the flute, the psalter, the lute, and all other musical instruments, while the bowls and cups went round, I was so happy that I forgot every sorrow in the world, saying to myself, ‘This is the life; alas, that it is fleeting.’ Then they said to me, ‘O our lord, choose from among us whomever you wish to spend this night with you.’

So Scheherazade entertains the king, with tantalizing tales which are always to be continued.

Today, we mostly know the

Arabian Nights

through the distorting filters of Hollywood and pantomime. They summon up a kaleidoscope of characters – Sinbad, Aladdin and the Thief of Baghdad; caliphs and sorcerers, viziers and merchants; and lots of girls, many of them slaves, but still talented and outspoken. We see all of them within the vast bustling landscapes of the great Muslim cities of the age: Baghdad at its height, of course, but also Cairo and, most importantly for these portraits, Samarra, the city that straddles the River Tigris north of Baghdad in modern Iraq.

Although we regard the

Arabian Nights

as exotic fiction, they tell us a lot about real life in the court of the Abbasid caliphs, the supreme rulers of the vast Islamic empire which in the eighth to tenth centuries stretched from central Asia to Spain. The historian Dr Robert Irwin has written a companion to the

Arabian Nights

and has traced its various historical connections:

Some of these stories do reflect the realities of Baghdad in the eighth and ninth centuries. The Abbasid caliphs employed a group of people known as Nudama – professional cup companions, whose job was to sit with the caliph as he ate and drank, and entertain him with edifying information, jokes, discussions of food and stories. So some of the stories in the

Arabian Nights

are part of the repertoire of these cup companions.It was a closed society. Few people ventured within its walls, and it’s been said that when a pious Muslim was summoned to see the caliph, he took with him his shroud – ordinary people rather feared what went on within the walls of the caliph’s palaces. I say ‘palaces’ advisedly, since the Abbasid caliphs seem to have had rather a disposable attitude towards them; once they had used one up they went and built another, and then abandoned it. So you get a succession of palaces, one after another in Baghdad, and then they moved to Samarra, where they did the same thing.

Most of the Abbasid palaces, both in Baghdad and in Samarra, are now in ruins. But some elements survive. At the British Museum we have a few fragments of painted plaster from the harem quarters of an Abbasid caliph, which take us back into the heart of the Islamic empire of the ninth century and show us the real counterparts of the girls from the

Arabian Nights

. For me, these fragments have more magic than any movie. They’re haunting glances across the centuries and could themselves inspire 1,001 stories.

The little portraits are probably all of women, although some may show boys. They are fragments of larger wall-paintings, and they link us directly to medieval Iraq. In Baghdad itself hardly anything architectural survives from this great age of glory around

AD

800, because the city was later destroyed by the Mongols. But luckily we can still get quite a good idea of what the Abbasid court looked like, because for almost sixty years its capital was moved seventy miles north to the brand new city of Samarra, and a lot of ancient Samarra survives.

At first sight these pictures are not very much to look at – they are really just scraps of paintings, and the largest is no bigger than a CD

disc. They are drawn fairly simply, with black outlines on a yellow ochre background, with just a few sketchy lines to capture the features, but there are flecks of gold in the painting which give us a hint of their earlier opulence. Like random pieces from a jigsaw puzzle, they make it difficult to guess what the bigger picture that they once came from might have been. Indeed, they’re not all portraits – some of the fragments show animals, some show bits of clothing and bodies. But the faces that are caught here have a definite sense of personality – there’s a clear air of melancholy in the eyes, as they look out at us from their enclosed, distant world.

These small pieces of plaster were excavated by archaeologists from the ruins of the Dar al-Khilafa palace, the main residence of the caliph in Samarra and the ceremonial heart of the new purpose-built capital city. Pleasure was built into the very name of the city, which was interpreted at the court as a shortened form of ‘Surra Man Ra’a’ – ‘He who sees it is delighted’. But beneath the frolicking there were ominous undercurrents. The decision in 836 to move the court from Baghdad to Samarra was taken in order to defuse dangerous tensions between the caliph’s armed guards and the inhabitants of Baghdad – tensions that had already ignited a string of riots. Samarra was intended to provide both a haven for the court and a safe base for the caliph’s army.

The new city of Samarra was on a grand scale, with palaces gigantic by the standards of any age, built at great cost; more than 6,000 different buildings have been identified. A contemporary description gives some impression of the spectacular nature of one of palaces of the caliph, al-Mutawakkil, perhaps the greatest builder of all the Abbasids: