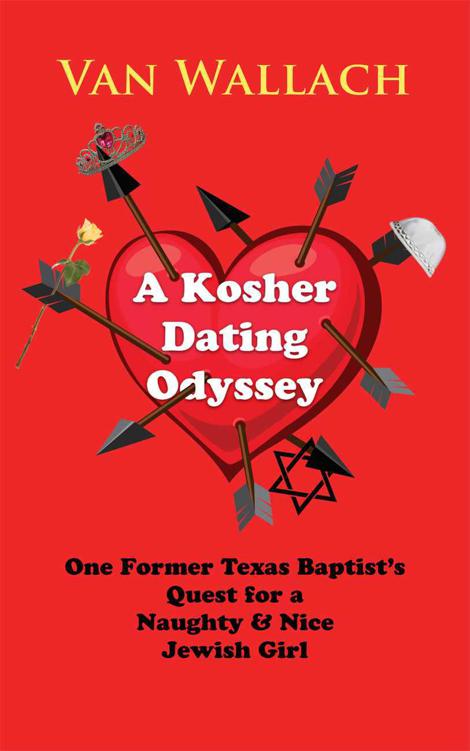

A Kosher Dating Odyssey: One Former Texas Baptist's Quest for a Naughty & Nice Jewish Girl

Authors: van Wallach

Tags: #Relationships, #Humor, #Topic, #Religion, #Personal Memoirs, #Biography & Autobiography

Published by Coffeetown Press

PO Box 70515

Seattle, WA 98127

For more information go to:

www.coffeetownpress.com

wallach.coffeetownpress.com

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Cover design by Sabrina Sun

A Kosher Dating Odyssey: One Former Texas Baptist’s Quest for a Naughty & Nice Jewish Girl

Copyright © 2012 by Van Wallach

Portions of this book previously appeared in JDate’s JMag, Blogcritics, Kesher Talk, Gringoes.com, The Princeton Alumni Weekly, The Daily Princetonian, and The Forward.

ISBN: 978-1-60381-132-3 (Trade Paper)

ISBN: 978-1-60381-133-0 (eBook)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011944487

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Produced in the United States of America

Chapter 1

Shards of Faith, Reassembled

I wear a

chai

—the Jewish letter symbolizing life—around my neck. I’ve studied Hebrew and Yiddish and have visited Israel. I subscribe to Jewish newspapers and have been told I look rabbinical; in fact, my great-great-grandfather, Heinrich (Chayim) Schwarz, was the first ordained rabbi in Texas.

Reading my religious résumé, you would never guess that I began my spiritual journey as a New Testament-reading, hell-fearing member of the First Baptist Church of Mission, Texas. How the heck, so to speak, did that happen? And how did I return to Judaism, which decades later led me to the whirling world of Jewish online dating?

The story started with my mother’s German ancestors moving to the United States in 1854. The earliest direct ancestor to get the hell out of Europe was my great-great-grandfather Adolph Lissner, who landed in New York in time to serve in the Civil War. A death notice in the

New York Times

(January 21, 1914) says he was eighty-four years old and “one of the oldest Free Masons, being a member of the Emmanuel Lodge since 1855. Mr. Lissner served during the civil war with Troop E, Third Regiment, New York Cavalry.” I found more in the New York municipal archives. He had died of pneumonia. He was the son of Samuel and Eva (Levine) Lissner. Following Jewish tradition, the names Samuel and Eva would surface in the generations flowing from Adolph. In fact, Adolph named his son, born in 1857, Samuel. The name carries over from generation to generation,

l’dor v’dor,

in Hebrew.

The Schwarz family—another band of plucky Prussians, as I like to call them—got its start in the U.S. in 1848, when Gabriel Schwarz moved to New York and then on to Charleston, S.C. Other family members followed, gravitating toward Texas. The book

Jewish Stars in Texas: Rabbis and Their Work

opens with a chapter on Rabbi Schwarz and his family and even features a photograph of the Rabbi Schwarz with his white beard and penetrating gaze on the cover.

My great-great-grandfather was the last Schwarz brother to pass over the Atlantic, leaving Posen, Germany and settling in Hempstead, Texas in 1873 with his wife Julia and five children, including fifteen-year-old Valeria. She would eventually marry Samuel Lissner. Their son, Jared, born in 1885, would be my grandfather. And Jared married Eva Michelson, daughter of German immigrants Lehman and Esther (Bath) Michelson. Their daughter Shirley Elizabeth, my mother, was born in Del Rio, Texas, on the banks of the Rio Grande, in 1920.

The Schwarzes and the Lissners typified the mid-nineteenth-century German Jewish wave of immigrants. They settled in small towns across Texas such as Hempstead, Marshall, Lockhart and especially Gonzales, where family members lived from the 1890s to the 1970s. Indeed, Gonzales had enough Jewish density to warrant two Jewish cemeteries. The one on Water Street contains the graves of the Michelsons, the Lissners, my mother, cousins and aunts and uncles. I try to visit Water Street whenever I’m in central Texas, along with Lockhart’s Kreuz Market for messy, finger-licking good barbecue.

That’s my mother’s background. My father’s family followed the arc of the next generation of immigrants. At the turn of the century they bolted out of Ukraine and other parts of Czar Nicholas II’s creaky, Jew-hating empire, settling in St. Louis. My grandfather, blessed with the unpronounceable name of Isadore Sribnovolace (evidently Russian for “silverhair”), was born in 1899 in the shtetl of Vishnivitz. The last name was changed to Wallace when the family reached the United States. According to family lore, my grandfather tired of being beat up for having a Christian name, so he changed it to the more Jewish-sounding “Wallach” (fun fact: the original name of Maxim Litvinov, Joseph Stalin’s foreign minister, was Meir Wallach).

The derivation of the name, I’ve discovered, goes in several directions. In German, “Wallach” means gelding, which doesn’t resonate with me. Wallachia is also a region in Romania. I fancy my roots go back to the vampires, but they don’t. My favorite explanation comes from the Wallachs UNITE group on Facebook, where somebody wrote, perhaps after a few shots of Slivovitz kosher plum brandy:

My mother met my father on a blind date in San Antonio in the mid 1950s. Both were Jewish, spoke English and had served in World War II. My father was on Okinawa, my mother was a Navy WAVE who served as a cryptographer in Washington, D.C., down the hall from Admiral William Halsey. When President Roosevelt died in 1945, she supposedly had the duty of flashing the news to the Navy. So the story goes.

Other that these factual overlaps I can discern no psychic or social similarities between my parents—my mother, the plain-spoken daughter of small-town Texas, and my father, a big-city dreamer from St. Louis. They married in March of 1955 in Temple Emanuel in McAllen, Texas, the city east of Mission with an established Jewish population. They soon moved to France so my father could pursue a career in the auto industry while working on a U.S. Air Force base. Their union produced two sons.

As in other spheres of European life, the Russians and the Germans couldn’t get along, so my mother returned to her hometown of Mission on the Mexican border—population 12,000 at the time, ninety percent Hispanic and founded in 1908. A hot, flat, primarily agricultural town. I have no memories of us together as a family, just a flashback to a car ride before Dad left. They had split up when she moved to Mission. My father remarried and moved to Michigan and then New York. My brother and I saw him one weekend in ten years, between 1962 and 1972. It was September 1970, when I should have been having the bar mitzvah I never had. He was forty-five—nine years younger than I am now.