A Maggot - John Fowles

Read A Maggot - John Fowles Online

Authors: John Fowles

A Maggot

John Fowles

1985

A MAGGOT IS the larval stage of a winged

creature; as is the written text, at least in the writer's hope. But

an older though now obsolete sense of the word is that of whim or

quirk. By extension it was sometimes used in the late seventeenth and

early eighteenth century of dance-tunes and airs that otherwise had

no special title ... Mr Beveridge's Maggot, My Lord Byron's Maggot,

The Carpenters' Maggot, and so on. This fictional maggot was written

very much for the same reason as those old musical ones of the period

in which it is set: out of obsession with a theme. For some years

before its writing a small group of travellers, faceless, without

apparent motive, went in my mind towards an event. Evidently in some

past; since they rode horses, and in a deserted landscape; but beyond

this very primitive image, nothing. I do not know where it came from,

or why it kept obstinately rising from my unconscious. The riders

never progressed to any destination. They simply rode along a

skyline, like a sequence of looped film in a movie projector; or like

a single line of verse, the last remnant of a lost myth.

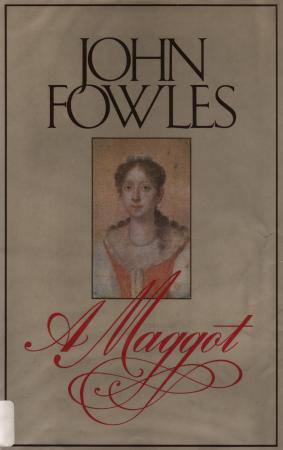

However, one day one of the riders gained a

face. By chance I acquired a pencil and water-colour drawing of a

young woman. There was no indication of artist, simply a little note

in ink in one corner, which seemingly says, in Italian, 16July 1683.

This precise dating pleased me at first as much as the drawing

itself, which is not of any distinction; yet something in the long

dead girl's face, in her eyes, an inexplicable presentness, a refusal

to die, came slowly to haunt me. Perhaps it was that refusal to die

that linked this real woman with another I have much longer admired,

from rather later in history.

This fiction is in no way biographically

about that second woman, though it does end with her birth in about

the real year and quite certainly the real place where she was born.

I have given that child her historical name; but I would not have

this seen as a historical novel. It is maggot.

John Fowles 1985

(Historical Chronicle scans provided as

separate files)

IN THE LATE and last afternoon of an April long

ago, a forlorn little group of travellers cross a remote upland in

the far south-west of England. All are on horseback, proceeding at a

walk along the moorland track. There lies about them, in the bleak

landscape, too high to have yet felt the obvious effects of spring,

in the uniform grey of the overcast sky, an aura of dismal monotony,

an accepted tedium of both journey and season. The peaty track they

follow traverses a waste of dead heather and ling; below, in a

steep-sided valley, stand unbroken dark woodlands, still more in bud

than in leaf. All the furthest distances fade into a mist, and the

travellers' clothes are by chance similarly without accent. The day

is quite windless, held in a dull suspension. Only in the extreme

west does a thin wash of yellow light offer some hope of better

weather to come.

A man in his late twenties, in a dark bistre

greatcoat, boots and a tricorn hat, its upturned edges trimmed

discreetly in silver braid, leads the silent caravan. The underparts

of his bay, and of his clothes, like those of his companions, are

mud-splashed, as if earlier in the day they have travelled in mirier

places. He rides with a slack rein and a slight stoop, staring at the

track ahead as if he does not see it. Some paces behind comes an

older man on a smaller, plumper horse. His greatcoat is in dark grey,

his hat black and plainer, and he too looks neither to left nor

right, but reads a small volume held in his free hand, letting his

placid pad tread its own way. Behind him, on a stouter beast, sit two

people: a bareheaded man in a long-sleeved blouse, heavy drugget

jerkin and leather breeches, his long hair tied in a knot, with in

front of him, sitting sideways and resting against his breast - he

supports her back with his right arm - a young woman. She is

enveloped in a brown hooded cloak, and muffled so that only her eyes

and nose are visible. Behind these two a leading-line runs back to a

pack horse. The animal carries a seam, or wooden frame, with a large

leather portmanteau tied to one side, and a smaller wooden box,

brassbound at its corners, on the other. Various other bundles and

bags lie bulkily distributed under a rope net. The overburdened beast

plods with hanged head, and sets the pace for the rest.

They may travel in silence, but they do not go

unobserved. The air across the valley opposite, above where its

steepness breaks into rocks and small cliffs, is noisy with deep and

ominous voices, complaining of this intrusion into their domain.

These threatening voices come from a disturbed ravenry. The bird was

then still far from its present rare and solitary state, but common

and colonial, surviving even in many towns, and abundantly in

isolated countryside. Though the mounted and circling black specks

stay at a mile's distance, there is something foreboding in their

alarm, their watchful hostility. All who ride that day, for all their

difference in many other things, know their reputation; and secretly

fear that snoring cry.

One might have supposed the two leading riders and

the humble apparent journeyman and wife chance-met, merely keeping

together for safety in this lonely place. That such a consideration -

and not because of ravens - was then requisite is plain in the

leading rider. The tip of a sword-sheath protrudes beneath his

greatcoat, while on the other side a bulge in the way the coat falls

suggests, quite correctly, that a pistol is hung behind the saddle.

The journeyman also has a brass-ended holstered pistol, even readier

to hand behind his saddle, while strung on top of the netted

impedimenta on the dejected pack-horse's back is a long-barrelled

musket. Only the older, second rider seems not armed. It is he who is

the exception for his time. Yet if they had been chance-met, the two

gentlemen would surely have been exchanging some sort of conversation

and riding abreast, which the track permitted. These two pass not a

word; nor does the man with the woman behind him. All ride as if lost

in their own separate worlds.

The track at last begins to slope diagonally down the

upland towards the first of the woods in the valley below. A mile or

so on, these woods give way to fields; and as far away again, where

the valley runs into another, can just be made out, in a thin veil of

wood smoke, an obscure cluster of buildings and an imposing church

tower. In the west the sky begins to show amber glints from invisible

breaks of cloud. That again, in other travellers, might have provoked

some remark, some lighter heart; but in these, no reaction.

Then, dramatically, another figure on horseback

appears from where the way enters the trees, mounting towards the

travellers. He does provide colour, since he wears a faded scarlet

riding-coat and what seems like a dragoon's hat; a squareset man of

indeterminate age with a large moustache. The long cutlass behind his

saddle and the massive wooden butt of a stout-cased blunderbuss

suggest a familiar hazard; and so does the way in which, as soon as

he sees the approaching file ahead, he kicks his horse and trots more

briskly up the hill as if to halt and challenge them. But they show

neither alarm nor excitement. Only the elder man who reads as he

rides quietly closes his volume and slips it into his greatcoat

pocket. The newcomer reins in some ten yards short of the leading

younger gentleman, then touches his hat and turns his horse to walk

beside him. He says something, and the gentleman nods, without

looking at him. The newcomer touches his hat again, then pulls aside

and waits until the last pair come abreast of him. They stop, and the

newcomer leans across and unfastens the leading-line of the

pack-horse from its ring behind the saddle. No friendly word seems

spoken, even here. The newcomer then takes his place, now leading the

pack-horse, at the rear of the procession; and very soon it is as if

he has always been there, one more mute limb of the indifferent rest.

They enter the leafless trees. The track falls

steeper and harsher, since it serves as a temporary stream bed during

the winter rains. More and more often comes the ring of iron shoes

striking stone. They arrive at what is almost a ravine, sloping faces

of half-buried rock, an awkward scramble even on foot. The leading

rider seems not to notice it, though his horse hesitates nervously,

picking its way. One of its hind feet slips, for a moment it seems it

must fall, and trap its rider. But somehow it, and the lurching man,

keep balance. They go a little slower, negotiate one more slip and

scramble with a clatter of frantic hooves, then come to more level

ground. The horse gives a little snorting whinny. The man rides on,

without even a glance back to see how the others fare.

The older gentleman has stopped. He glances round at

the pair behind him. The man there makes a little anti-clockwise

circle with a finger and points to the ground: dismount and lead. The

man in the scarlet coat at the rear, wise from his own recent upward

passage, has already got down, and is tying the pack horse to an

exposed root by the trackside. The older gentleman dismounts. Then

his counsellor behind jumps off, with a singular dexterity, kicking

free of his right stirrup and swinging his leg, over the horse's back

and slipping to the ground all in one lithe movement. He holds his

arms out for the woman, who leans and half sinks towards him, to be

caught, then swung free and set down.

The elderly man goes gingerly down the ravine,

leading his pad, then the bareheaded man in the jerkin, and his

horse. The woman walks behind, her skirts held slightly off the

ground so that she can see her feet and where they are placed; then

the last man, he in the faded scarlet coat. Once down, he extends the

rein of his riding-horse to the man in the jerkin to hold, then turns

and climbs heavily back for the pack-horse. The older gentleman

laboriously mounts again, and rides on. The woman raises her hands

and pushes back the hood of her cloak, then loosens the white linen

band she has swathed round the lower part of her face. She is young,

hardly more than a girl, pale-faced, with dark hair bound severely

back beneath a flat-crowned chip, or willow-shaving, hat. Its

side-brims are tied down against her cheeks, almost into a bonnet, by

the blue kissing-ribbons beneath her chin. Such a chip or wheat-straw

hat is worn by every humbler English country-woman. A little fringe

of white also appears beneath the bottom of her cloak: an apron. She

is evidently a servant, a maid.

Unfastening the top of her cloak, and likewise

undoing the kissing-ribbons, she goes beside the track a little ahead

and stoops where some sweet-violets are still in flower on a bank.

Her companion stares at her crouched back, the small movements of her

hands, the left one picking, ruffling the heart-shaped green leaves

to reveal the hidden flowers, the right one holding the small sprig

of deep mauve heads she has found. He stares as if he does not

comprehend why she should do this.

He has a strangely inscrutable face, which does not

reveal whether its expressionlessness is that of an illiterate

stupidity, an ignorant acceptance of destiny not far removed from

that of the two horses he is holding; or whether it hides something

deeper, some resentment of grace, some twisted sectarian suspicion of

personable young women who waste time picking flowers. Yet it is also

a strikingly regular, well-proportioned face, which, together with

his evident agility, an innate athleticism and strength, adds an

incongruous touch of the classical, of an Apollo, to one of plainly

low-born origins - and certainly not Greek ones, for his strangest

features are his eyes, that are of a vacant blue, almost as if he

were blind, though it is clear he is not. They add greatly to the

impression of inscrutability, for they betray no sign . of emotion,

seem always to stare, to suggest their owner is somewhere else. So

might twin camera lenses see, not normal human eyes.

Now the girl straightens and comes back towards him,

smelling her minuscule posy; then gravely holds the purple flowers,

with their little flecks of orange and silver, out and up for him to

smell as well. Their eyes meet for a moment. Hers are of a more usual

colour, a tawny brown, faintly challenging and mischievous, though

she does not smile. She pushes the posy an inch or two nearer still.

He briefly sniffs; nods, then as if they waste time, turns and mounts

with the same agile grace and sense of balance that he showed before,

still holding the other horse's rein. The girl watches him a moment

more while he sits above, tightening the loosened linen muffler,

pulling it to cover her mouth once more. She tucks her violets

carefully inside the rim of white cloth, just below her nostrils.