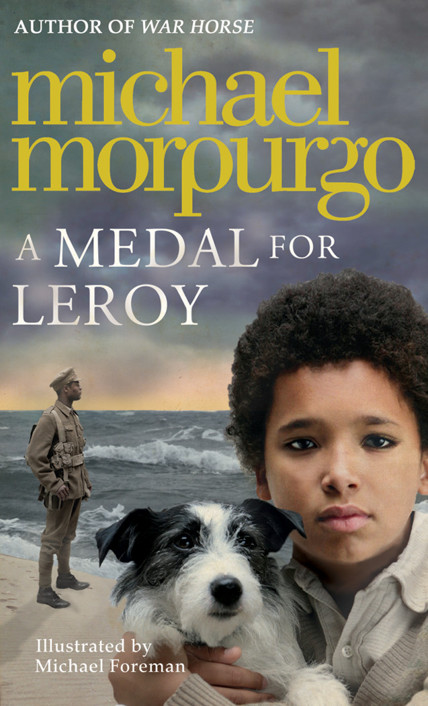

A Medal for Leroy

Authors: Michael Morpurgo

Contents

Read it, his eyes were telling me

Who I am, What I’ve done, and Who you are

hen it came to it, I wasn’t entirely sure what we were doing walking up that hillside in Belgium. Christine’s hand came into mine as we walked. Were we burying the past, righting a wrong, or simply paying our respects? Were we doing it for ourselves, or was it for Maman and Papa, or Auntie Snowdrop and Auntie Pish, or Grandfather Leroy?

hen it came to it, I wasn’t entirely sure what we were doing walking up that hillside in Belgium. Christine’s hand came into mine as we walked. Were we burying the past, righting a wrong, or simply paying our respects? Were we doing it for ourselves, or was it for Maman and Papa, or Auntie Snowdrop and Auntie Pish, or Grandfather Leroy?

It had happened somewhere in this field, definitely this field – we knew that much from the maps. We knew Leroy had run on ahead of the others, that he was leading the attack. But where exactly had it happened? Closer to the crest of the hill, near the trees? Probably. Nearer the farm buildings? Maybe. We had so little to go on.

Jasper had run on ahead of us, and was snuffling about under a fallen tree at the edge of the wood. Then he was exploring along the tree line on the crest of the hill, nose to the ground.

“Wherever Jasper stops,” I said, “if he ever does, wherever he next sits down for a rest, that’s where we’ll do it. Agreed?”

the war. When I was a boy, my friends called me ‘Poodle’. I didn’t mind that much. I’d have preferred they called me Michael – it was my real name after all – but they rarely did.

the war. When I was a boy, my friends called me ‘Poodle’. I didn’t mind that much. I’d have preferred they called me Michael – it was my real name after all – but they rarely did.

I didn’t have a father, not one that I ever knew anyway. You don’t miss what you’ve never had, so I didn’t mind that either, not much. There were compensations too. Not having a father made me different. Most of my pals at school lived in two-parent families – a few had three or even four parents, if you count step-families. I had just the one parent, Maman, and no brothers and sisters either. That made me special. I liked being different. I liked feeling special.

Maman was French, and spoke English as if it was French, with lots of hand-waving, conducting her words with her hands, her voice as full of expression as her eyes. We spoke mostly French at home – she insisted on it, so that I could grow up ‘dreaming in both languages’ as she put it, which I could and still do; but that was why her English accent never improved. At the school gates when she sometimes came to fetch me I’d feel proud of her Frenchness. With her short dark hair and olive brown skin, and her accent, she neither looked nor sounded like the other mothers. We had a book at school on great heroes and heroines, and Maman looked just like Joan of Arc in that book, only a bit older.

But being half French had its difficulties. I was ‘Poodle’ on account of my frizzy black hair, and because I was a bit French. Poodles are known in England as a very French kind of dog, so Maman told me. Even she would call me ‘my little poodle’ sometimes, which I have to say I preferred to ‘

mon petit chou

’ – my little cabbage, her favourite name for me. At school I had all sorts of other playground nicknames besides ‘Poodle’. ‘Froggie’ was one, because in those days French people were often called ‘Frogs’. I didn’t much like that. Maman told me not to worry. “It’s because they think we all eat nothing but frogs’ legs. Just call them ‘Roast beef’ back,” Maman told me. “That’s what we French call the English.”

So I tried it. They just thought it was funny and laughed. So from then on it became a sort of joke around the school – we’d even have pick-up football teams in the playground called the Roastbeefs and the Froggies. In the end I was English enough to be acceptable to them, and to feel one of them. Maybe that was why I never much minded what they called me – it was all done in fun, most of the time, anyway.

Somehow it had got around the school, and all down the street, about my father – I don’t know how, because I never said anything. Everyone seemed to know why Maman was always alone – and not just at the school gates, but at Nativity plays at Christmas time, at football matches. It was common knowledge that my father had been killed in the war. Whenever the war was spoken of around me – and it was spoken of often when I was growing up – voices would drop to a respectful, almost reverential whisper, and people would look at me sideways, admiringly, sympathetically, enviously even. I didn’t know much more about my father than they did. But I liked the admiration and the sympathy, and the envy too.

All Maman had told me was that my father was called Roy, that he had been in the RAF, a Spitfire pilot, a Flight Lieutenant, and that he had been shot down over the English Channel in the summer of 1940. They had only been married for six months – six months, two weeks and one day – she was always very precise about it when I asked about Papa. He’d been adopted as a baby by his aunties, after their sister, his mother, had been killed in a Zeppelin raid on London. So he’d grown up with his aunties by the sea in Folkestone in Kent, and gone to school there. He was twenty-one when he died, she said.

That’s just about all I knew, all she would tell me anyway. No matter how much I asked, and I did, and more often as I grew up, she would say little more about him. I know now how painful it must have been for her to talk of him, but at the time I remember feeling very upset, angry almost towards her. He was my father, wasn’t he? It felt to me as if she was keeping him all for herself. Occasionally after a football match, or when I’d run down to the corner shop on an errand for old Ma Merritt who lived next door to us, Maman might say something like: “Your Papa would have been so proud of you. I so wish he’d known you.” But never anything more, nothing about him, nothing that helped me to imagine what sort of a man he might have been.

Sometimes, on the anniversary of his death or on Remembrance Day perhaps, she’d become tearful, and bring out her photograph album to show me. She couldn’t speak as she turned the pages and I knew better than to ask any more of my questions. It was as I gazed at him in those photos, and as he looked back up at me, that I really missed knowing him. In truth, it was only ever a momentary pang, but each time I looked into his face, it set me wondering. I tried to feel sad about him but I found it hard. He was, in the end, and I knew it, just a face in a photo to me. I felt bad about it, bad about not feeling sad, I mean. If I cried with Maman – and I did sometimes over that album – I cried only because I could tell Maman was aching with grief inside.

Some nights when I was little, I’d hear Maman crying herself to sleep in her room. I used to go to her bed then and crawl in with her. She’d hold me tight and say nothing. Sometimes at moments like that I felt she really wanted to tell me more about him, and I longed to ask, but I knew that to ask would be to intrude on her grief and maybe make it worse for her. Time and again I’d let the moment pass. I’d try asking her another time, but whenever I did, she’d look away, clam up, or simply change the subject – she was very good at changing the subject. I didn’t understand then that her loss was still too sharp, her memories too fresh, or that maybe she was just trying to keep her pain to herself, to protect me perhaps, so as not to upset me. I only knew that I wanted to know more about him, and she wouldn’t tell me.