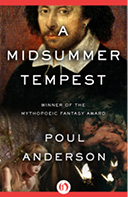

A Midsummer Tempest (30 page)

Tethering their horses, Rupert and Jennifer climbed to the top. She shivered. He brought an arm and a part of his cloak around her shoulders. “Art chilly, dearest?” he asked. His voice was lost in ringing silence.

She snuggled. “Never next to thee.”

“I likewise. But let’s do this final duty as quickly as may be, and hasten back to where men dwell. We’ve known sufficient strangeness. Now that we have been wed, I fain would clasp a sweet reality, too good for dreams.”

Rupert raised the staff he bore, she the book. Silver flashed on their hands. “King Oberon and Queen Titania,” he said louder, “this one last time we call you forth to us. By the moon’s witchery, in Yuletide season whose joyousness foretells a year reborn, come out to claim what rightfully is yours.”

A glow awoke, and the rulers of Faerie stood before them. A new majesty, or an old one returned, made the humans bow very deeply.

Yet the queen’s words sang mild: “Greeting, good Rupert, gentle Jennifer. How happy ’tis to welcome you again.”

“More than your kin, the Half-World owes you thanks,” Oberon said. “Ye have lit countless candles in a shadow. What luck and love may lie within our gift we promise you, each night ye both do live. And when at last your Father bids you home, ever shall elven songs remember you, ever shall springtime garland your graves in blooms, ever shall fortune follow your children’s children, as long as kindly magic does endure. May it not fail before the Judgment Day.”

“We thank you too, and most sincerely hope”—Rupert hesitated, shook his head—“though I know not—know not—and cannot know—” Straightening: “It hurts that we must make a severance. But we’re too much of flesh, my bride and I, and too much mortal world and work await. These eyes are blind to color by the moon; these heavy ears hear birdsong but are deaf to thin delirious music of the bat; these fingers are too coarse for harvesting of dewdrops or for weaving spider-silk; these nostrils drink no odor from a stone; these tongues can find no taste in thistledown. So we’ll no longer tread in Faerie’s rings or follow its wild stars beyond the wind. We’ll seek what wonder is in common earth.”

Jennifer seized the Queen’s hand. “I think you also always will be there,” the girl said. Titania smiled.

“Take back the serpent sigils that you gave,” Rupert told Oberon. “Someday, maybe, you’ll find a man with strength to keep that flame—”

“Or with less blood than thine,” Jennifer interrupted him. “I’ll see thou’lt never wish for more than me!”

Amusement went mercurial across the kingly pair. Rupert continued doggedly; “Likewise take off the book and staff we bear, old Prospero’s, to keep where seems you best. Greet Ariel from us.”

“And Caliban,” Jennifer murmured. “And … there’s a lad—no cause for jealousy—your Majesties must know whom ’tis I mean—If sometime soon, along some twilit lane, he might meet one who has a heart to swap. … And oh, I know so many more besides—”

“Dear girl, we cannot ward the living earth,” Oberon answered, grave again and softly, “no more than can the rivers, hills, or sky. That loneliness is laid upon thy race.” He and his queen gathered the things of sorcery.

“Fare always well.” He raised the staff. “Titania, away!”

They were gone into the radiant winter night.

After a long while, Rupert took Jennifer’s arm and said, “Come, darling, let’s get home before the day.”

THE TAPROOM OF THE OLD PHOENIX.

T

HEY

were many gathered this evening, to sit before the innkeeper’s fire, enjoy his food and drink and regale him with their tales. Valeria Matuchek leaned against the bar, a pint in her fist, the better to oversee them. A few she recognized, or thought she did—brown-robed monk at whose feet lay a wolf, gorgeously drunk Chinese from long ago whose calligraphic brush was tracing a poem, rangy fellow nearby whose garb was hard to place but who bore a harp, large affable blond man in high boots and gray leather with an iridescent jewel on his wrist, lean pipe-smoking Victorian and his slightly lame companion, wide-eyed freckle-faced boy and Negro man in tatterdemalion farm clothes, coppery-skinned feather-crowned warrior who held a calumet and a green ear of maize—but of the rest she was unsure. Several were not human.

Being impatient to hear everything that could be spoken and translated before they must depart, she finished her turn rather hastily:

“Yes, I came back through that universe, and spent a while learning how things worked out. Earlier, I’d gone to history books elsewhere, for background. Evidently this had to be the time-line where the romantic reactionaries do better than anywhen else. And …

this

Charles the First was either a wise man from the beginning, or chastened by experience.”

She shrugged. “I’m not sure how much difference it’ll make in the long run. In my history, Prince Rupert—well, he didn’t simply help invent the mezzotint, he became a scientist, a sponsor of explorations, a founder of the Royal Society. …I don’t think that in any cosmos he’ll sit smug on his victories. And they’ve got a new world a-borning there too, the real New World, the machine

—science itself, which matters more; reason triumphant, which matters most—no stopping it, because along with the bad there’s too much good, hope, challenge, liberation—

“Well.” She drained her tankard and held it out for a refill. “Nothing ever was forever, anyway. Peace never came natural. The point is, it can sometimes be won for some years, and they can be lived in.

“Enough. I hope you’ve enjoyed my story.”

Poul Anderson (1926–2001) grew up bilingual in a Danish American family. After discovering science fiction fandom and earning a physics degree at the University of Minnesota, he found writing science fiction more satisfactory. Admired for his “hard” science fiction, mysteries, historical novels, and “fantasy with rivets,” he also excelled in humor. He was the guest of honor at the 1959 World Science Fiction Convention and at many similar events, including the 1998 Contact Japan 3 and the 1999 Strannik Conference in Saint Petersburg, Russia. Besides winning the Hugo and Nebula Awards, he has received the Gandalf, Seiun, and Strannik, or “Wanderer,” Awards. A founder of the Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America, he became a Grand Master, and was inducted into the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame.

In 1952 he met Karen Kruse; they married in Berkeley, California, where their daughter, Astrid, was born, and they later lived in Orinda, California. Astrid and her husband, science fiction author Greg Bear, now live with their family outside Seattle.

All rights reserved, including without limitation the right to reproduce this ebook or any portion thereof in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, events, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 1974 by Trigonier Trust

Cover design by Jason Gabbert

978-1-4976-9424-8

This edition published in 2014 by Open Road Integrated Media, Inc.

345 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10014

FROM OPEN ROAD MEDIA