A Nice Little Place on the North Side: Wrigley Field at One Hundred (10 page)

Read A Nice Little Place on the North Side: Wrigley Field at One Hundred Online

Authors: George Will

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Sports & Recreation, #Baseball, #History

Veeck went on to own the St. Louis Browns, from 1951 through 1953.

That team frequently played in front of such small crowds that Veeck used to joke that when a fan called to ask what time that day’s game would start, he would answer, “What time can you get here?” The ivy he planted probably drew more fans to Wrigley Field than his Browns team drew to Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis.

On September 17, 1937, the

Chicago Tribune

carried a story with this headline: “New Wrigley Field Blooms in Scenic Beauty—and Scoffers Rush to Apologize.” One of the scoffers was the author of the story, Edward Burns, who had written a series of grumpy reports about changes under way at the field, including enlargement of the bleachers. Now, however, he was prepared to “emboss an apologetic scroll to P. K. Wrigley, owner of the most artistic ballpark in the majors.” Burns estimated that the park was valued at $3 million.

Paul Dickson is the author of a 2012 biography of Veeck that contains some fascinating details about Veeck’s job supervising Wrigley Field’s concessions. Veeck hired vendors to sell programs, peanuts, and other ballpark staples, and one of his hires was known as a “duker,” meaning a sort of hustler. This young fellow, named Jacob Leon Rubenstein, had been born in 1911 and had developed some disagreeable tricks of the vendor’s trade, such as bumping into a startled fan, placing the program in his hand, and then

demanding a quarter in payment. Rubenstein also hawked paper birds tied to wooden sticks. The birds chirped when the sticks were twirled, and he would foist them on children in the hope that they would pressure their parents into purchasing the birds.

Veeck said the Cubs assigned someone with binoculars to monitor this vendor “to make sure they were getting their share of his nefarious sales.”

This vendor did not linger in Chicago. Rubenstein went west, changing his name to Jack Ruby. In 1947, he settled in Dallas, where he opened several seedy nightclubs. On November 22, 1963, distraught about the assassination of President John Kennedy, the former vendor put his snub-nosed Colt Cobra .38-caliber revolver in his jacket pocket and headed to the Dallas police headquarters, where Oswald was being held; there, he passed himself off as a newspaper reporter to attend a press conference about the assassination. Two days later, he returned to that building and fatally shot Lee Harvey Oswald. Ruby was convicted of murder with malice and sentenced to death. His conviction was overturned, and he succumbed to lung cancer while awaiting a new trial. He died at Parkland Hospital, where Kennedy had been declared dead, and where Oswald had died from Ruby’s gunshot. Ruby is buried in Westlawn Cemetery in Norridge, Illinois, nine miles from Wrigley Field.

Veeck’s supervision of Wrigley Field’s concessions also brought him into contact with a short, stocky go-getter salesman of paper cups and Multimixer milk-shake machines. The salesman was an ardent Cub fan. He was also a

pest, constantly badgering Veeck to stock up on more cups. Born in 1902 in Oak Park, Illinois, Ray Kroc was a cheerful Willy Loman. The son of immigrants from Czechoslovakia, he was as unpretentious as a hamburger, as salty as a French fry, and as American as frozen apple pie. In 1945, after sixteen years of the Depression and war, Americans were eager to get into their cars and hit the road, which is what Kroc did to hawk his cups and machines. In 1954, when he got an astonishing order for eight milk-shake machines from a restaurant in San Bernardino, California, owned by two brothers, he went there to take a look. One look was all he needed.

The Second World War had accustomed many millions of American palates to the standardized fare of Crations and factory canteens. Standardization was what the San Bernardino brothers offered. Kroc convinced Richard and Maurice McDonald to accept a small percentage of his gross revenues, if there were to be any, in exchange for his use of their name and business model, which involved selling only hamburgers (fifteen cents), fries (ten cents), and milk shakes (twenty cents). He opened his first restaurant in Des Plaines, a Chicago suburb fifteen miles from Wrigley Field. By the time he died, in 1984, he had satisfied his baseball yearnings by buying the San Diego Padres. As Wrigley Field turns one hundred, there are more than thirty-four thousand McDonald’s restaurants worldwide.

Paul Sullivan, who has been covering baseball for the

Chicago Tribune

since 1989 and has been working for the paper since 1981, remembers that “in the early 1980s,

Veeck used to hang out at Wrigley Field.” When Veeck sold the White Sox, in 1981, he thought the new owners disparaged his years on the South Side, so he returned to Wrigley Field to slake his undiminished thirst for baseball. And for beer. “He could drink like a fish,” Sullivan recalls, “but never had to go to the bathroom.” It was, Sullivan says, as though Veeck’s wooden leg—a war wound, then thirty-six surgeries, cost him a leg—were hollow. It wasn’t, but it did have a slide-out ashtray, which was cheeky for a man with cancer. But, then, insouciance was the essence of Veeck, the baseball lifer who one night in 1937 gave Wrigley Field the look that to this day defines it. Late in his life he used to sit high above the ivy he had planted, in the upper part of the center-field bleachers. These years were, Sullivan says with a tone of some regret, “the last gasp of the old Wrigley Field.” He means that those were the last days before the fans, their appetite for success whetted by the 1984 season, began to become impatient for wins. Before that, says Sullivan, “The team was bad and the fans weren’t that bothered by it.”

Bill Veeck’s winding baseball trail took him back to where he began. He died in 1986. He was cremated, and his ashes are in Oak Woods Cemetery, fifteen miles from Wrigley Field. He is spending eternity in interesting company. Also buried there, in addition to Chicago gangsters Big Jim Colosimo and Jake “Greasy Thumb” Guzik, are Jesse Owens, the hero of the 1936 Berlin Olympics, and Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis.

In 1919, two years after the Russian Revolution announced the agenda of abolishing private property, William Wrigley bought a fifty-eight-thousand-acre island.

Santa Catalina, the “isle with the smile,” is about twenty miles off California’s Orange County. The Cubs conducted spring training on the island from 1921 until shifting to Mesa, Arizona, in 1951. That, however, is not why Santa Catalina deserves an important paragraph in American history. Here is why:

Ronald Wilson Reagan of Dixon, Illinois, graduated from Eureka College in Eureka, Illinois, in 1932, the trough of the Depression. The unemployment rate was 26 percent when he hitchhiked home to Dixon, where he applied for a $12.50-a-week job managing the sporting goods section of a store Montgomery Ward was opening there. The job went to one of his high school classmates, which was a fortunate failure for Reagan, who set out in his family’s car to seek employment as a radio announcer. After a brief and rocky stint with WOC in Davenport, Iowa, where he was miscast as a disc jockey, he was offered a chance to broadcast the Drake Relays, one of the nation’s premier track meets, for station WHO in Des Moines. The station liked what it heard and made Reagan a sportscaster; his tasks included recreating Cubs games as details trickled in over a telegraph wire. In 1937, Reagan persuaded the station to finance his drive to southern California to report about the Cubs’ spring training on Santa Catalina Island.

He had dinner in Los Angeles with a former WHO colleague, who put him in touch with an agent, who placed the famous call to a casting director at Warner Bros.: “I have another Robert Taylor sitting in my office.”

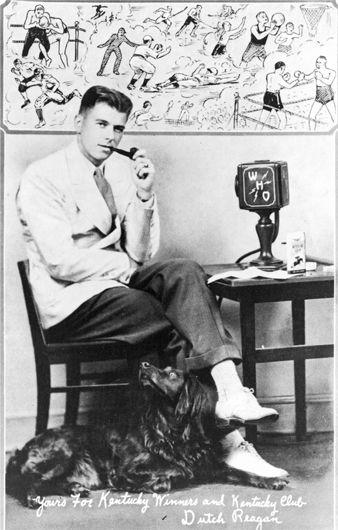

Dapper Dutch: Santa Catalina Island, here I come. (

photo credit 1.11

)

The unimpressed director supposedly replied that God made only one Robert Taylor. Nevertheless, Reagan got his foot in Hollywood’s door. When he was still twenty-eight years away from winning the presidency, he starred in the 1952 movie

The Winning Team

, playing a former Cubs pitcher with a presidential name: Grover Cleveland Alexander,

who, like Reagan, was the son of an alcoholic. Alexander suffered from alcoholism and epilepsy, a bad combination, but not bad enough to prevent him from winning 373 games—128 of them for the Cubs—and becoming, in 1938, a member of the third class elected to the Hall of Fame.

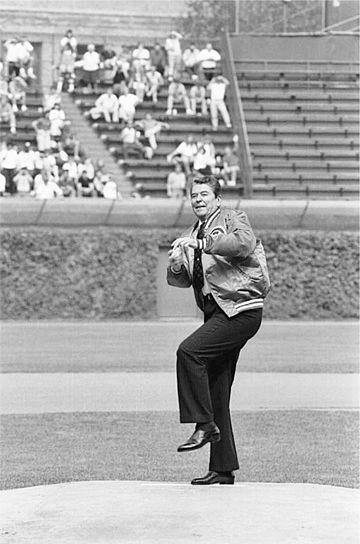

A right-hander on the Wrigley Field mound. (

photo credit 1.12

)

In his 1990 memoir,

An American Life

, Reagan wrote, “At twenty-two I’d achieved my dream: I was a sports announcer. If I had stopped there, I believe I would have been happy the rest of my life.” His talent for happiness is apparent in the

this page

photo of him on Wrigley Field’s pitcher’s mound.

The Midwest has supplied the two longest-serving commissioners of baseball: the first and the ninth, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis and Allan H. “Bud” Selig. Between them, they governed the sport, through 2013, for forty-six years—Landis for twenty-four and Selig for twenty-two—and they did so from the Midwest.

Landis grew up in Logansport, Indiana, and earned his law degree from what is now Northwestern University Law School. When he was commissioner, the door of his Michigan Avenue office, which was about a mile south of the Wrigley Building, had a sign of majestic terseness:

“Baseball.” With his chiseled features; unsmiling, mail-slot mouth; and shock of white hair, Landis looked like a pewter statue of the virtue Rectitude. The fact that he governed like Lenin—more decisively than justly—mattered less than his visage. After baseball’s trauma of the 1919 Black Sox scandal, the baseball owners hired Landis to look stern, which he often did from the front row of the box seats at Wrigley Field, not far from where Al Capone occasionally sat.

Selig, a native of Milwaukee, has been the un-Landis. He is never autocratic, and he has a genius for the politics of a small group—the thirty owners. No one really knows how Selig has made many of his decisions or how he has produced support for them among those thirty fractious constituents. Like Dwight Eisenhower, Selig practices hidden-hand leadership. What is not hidden is its effectiveness. It has transformed Major League Baseball from a $1.2 billion business in 1992, when he became acting commissioner, to what probably will be a $8 billion business in Wrigley Field’s one hundredth year. Selig has a posh corner office in Major League Baseball’s headquarters on Park Avenue in Manhattan, but he rarely uses it. He prefers his office on the thirtieth floor of a Milwaukee bank building overlooking Lake Michigan, less than ninety miles from Wrigley Field, where in 1944 he saw his first major league game. He was a Cub fan until the Braves arrived in Milwaukee from Boston in 1953, when he began rooting for the home team. A good choice, that. The Braves won the World Series in 1957. Cub fans are still waiting.