A Nice Little Place on the North Side: Wrigley Field at One Hundred (6 page)

Read A Nice Little Place on the North Side: Wrigley Field at One Hundred Online

Authors: George Will

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Sports & Recreation, #Baseball, #History

In July 1926, the

Chicago Tribune

carried this little item:

WHIPPED FOR STAYING OUT LATE, GIRL RUNS AWAY

Violet Popovich, 15 years old, 4516 E. Harrison Street, was whipped for going to a movie with a boy and staying out late last Sunday night. Monday she ran away from home and yesterday the Fillmore Street police were asked to find her.

Violet ran away from home—such as it may have been; she spent much of her childhood in an orphanage—at age fifteen. At seventeen, when she started calling herself Violet Valli, she became a dancer in a chorus line. At eighteen, she married. And along the way she became rather too interested in the Cubs. Or at least some of them. And some ballplayers who were not Cubs. Ehrgott found that a Chicago paper had reported that before she met Billy Jurges, Valli had been “friendly” with at least one other major league player, one with a Cubs uniform in his future: Leo Durocher, then a Cincinnati Reds infielder.

When Abraham Lincoln met Harriet Beecher Stowe, the author of

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

, the novel that added fuel to the slavery controversy, he supposedly (this comes from Stowe family lore) addressed her as “the little lady who started the big war.” Violet Valli was the spark that lit the fuse that led to the most famous event in the history of Wrigley Field, an event that almost certainly did not happen.

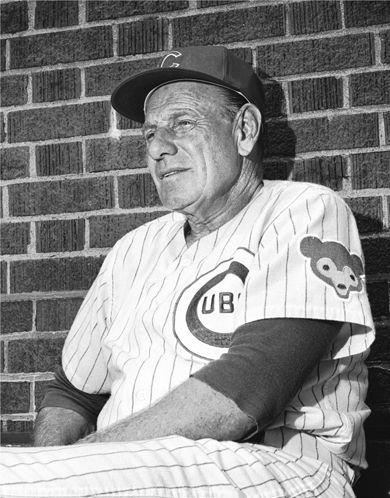

Leo Durocher: Nice guys need not apply. (

photo credit 1.4

)

Not that that matters. The fact is that most baseball fans believe that Babe Ruth actually hit a “called shot” during the 1932 World Series. So it is part of the ballpark’s story, even though no one will ever really know whether Ruth pointed to designate the spot in the center-field bleachers where, a moment later, he hit the pitch thrown by the Cubs’ Charlie Root.

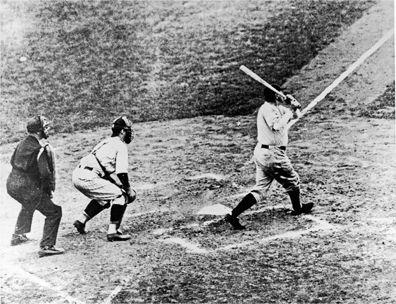

Ruth hits the “called shot.” Or not. (

photo credit 1.5

)

A good tutor about this episode is Leigh Montville, who, in his 2006 biography,

The Big Bam: The Life and Times of Babe Ruth

, begins the story with “Violet (What I Did for Love) Valli—the Most Talked About Woman in Chicago.” That is how she was billed during her scheduled twenty-two-week vaudeville show. In 1932, she was twenty-one and smitten with Billy Jurges, twenty-four, the Cubs’ shortstop. His affections may once, or occasionally, have been as ardent for her as hers were for him, but his were decidedly less constant.

So on July 6, 1932, Violet, packing a .25-caliber revolver, went to the room at the Hotel Carlos where Jurges

lived during the season.

Having written a farewell note telling her brother that “life without Billy isn’t worth living,” she intended to kill Billy and then herself. Jurges admitted her to his room, and when she began to execute her plan, he disarmed her, but not before taking two bullets: one in the ribs, the other in a hand. He and she, together for one last time, were rushed to the same hospital.

The judge presiding over a dispute about possession of some inconvenient letters between Valli and Jurges—and perhaps another Cubs star—made clear his judicial priorities: “I want to keep this case under my jurisdiction to prevent embarrassment to the Cubs so that their chances of winning the pennant will not be harmed. I don’t want this thing to worry Jurges.”

The Cubs had another worry: They needed a shortstop without a bullet wound. So they signed Mark Koenig. He had played that position five years earlier on what many people consider the best team in baseball history, the 1927 Yankees. He had hit a triple and scored when Ruth hit his sixtieth home run. Koenig had been released by the Tigers in the spring of 1932 and was playing for the San Francisco Seals when the Cubs called. He promptly joined the team, and his .353 batting average for the Cubs helped them win the pennant by four games over the Pirates.

But before the World Series began, the Cubs’ players voted on the distribution of the team’s World Series payout and awarded Koenig only a half share. The winner’s share of the 1932 World Series would turn out to be $5,231.77, and each of the losers would get $4,244.60. Koenig’s

former teammates on the Yankees were not amused, and they expressed their (somewhat opportunistic) indignation in what used to be called “bench jockeying.” Ruth, exuberant in most things, was especially so in excoriating the Cubs as cheapskates. Ruth did this even though there was no love lost between him and Koenig; Ruth had grappled with the shortstop in a clubhouse fight when Koenig made a disparaging remark about Ruth’s new wife, Claire.

The Cubs, Montville writes, responded to the Yankees’ insults “with questions about [Ruth’s] parentage, his increasing weight, his racial features, his sexual preferences, and whatever else they could invent.” In the rough-and-tumble world of baseball back then, the word “nigger” was bandied about casually. “It was,” says Montville correctly, “all familiar baseball stuff for the time, but with an exaggerated edge.”

The Yankees won the first two games, in New York, and arrived at Wrigley Field for Game 3 to see a strong wind blowing out toward right field. In the top of the first inning, with two runners on, and after two lemons had been thrown at him from the stands, Ruth homered off Charlie Root. In the third, Ruth flied out to deep right center. In the fifth, with the score 4–4, the bases empty, and Root still on the mound, Ruth took a first pitch for a called strike. Then, Montville writes, Ruth looked toward the Cubs’ dugout and “put up one finger, as if to say, ‘That’s just one strike.’ ” Ruth might have been responding to a Cubs pitcher, Guy Bush, who was standing on the top step of the dugout. After Root threw two pitches that were called

balls, Ruth took a second called strike and this time held up two fingers. “He then pointed,” says Montville. “Where he pointed is a question, but legend has it that he pointed to dead center field.” What we do know, and perhaps all that we know for sure, is this from Montville:

Cubs catcher Gabby Hartnett later said that Ruth said, “It only takes one to hit.” [Lou] Gehrig, in the on-deck circle, said Ruth said to Root, “I’m going to knock the next one down your goddamned throat.” A pair of 16mm home movies discovered more than half a century later seemed to indicate that Ruth might have pointed at the Cubs bench and at Bush rather than dead center field (maybe Ruth wanted to knock the ball down Bush’s goddamned throat?), but both films were taken from angles that left room for doubt.

Be that as it may, Ruth hit Root’s next pitch, a slow curve, up into the wind and out of the park between the center-field scoreboard and the right-field bleachers. Montville says that as Ruth rounded third in front of the Cubs’ dugout, he held up four fingers: Four bases? Four games? Gehrig knocked Root’s next pitch out of the park, and the Yankees won Game 3, 7–5. The next day they completed their sweep, 13–6.

Only one reporter among the throng of newspaperman at the game said in his story that before Root delivered the pitch, Ruth pointed to where he was going to hit it. But

the Scripps Howard News Service, for which Joe Williams wrote, headlined his story “Ruth Calls Shot.” So there.

The truth is that the truth will never be known. But as Montville says, Ruth had a showman’s boisterous habit of promising to hit home runs for this or that person or occasion, and often did. On some later occasions, Ruth claimed that he called his shot in Game 3 of the Series. On other occasions, he said that “only a damn fool” would do such a thing. The next spring, however, he attended a New York cocktail party hosted by the most famous sportswriter of the day, Grantland Rice. There the wife of the most famous political columnist of the day, Walter Lippmann, asked Ruth what had happened the previous autumn.

In his 1955 autobiography,

The Tumult and the Shouting

, Rice recounted Ruth’s response, but without Ruth’s tangy language, which Montville supplies for our less decorous age:

“The Cubs had fucked my old teammate Mark Koenig by cutting him for only a measly fucken half share of the Series money. Well, I’m riding the fuck out of the Cubs, telling ’em they’re the cheapest pack of fucken crumbums in the world.… [Root] breezes the first two pitches by—both strikes! The mob’s tearing down Wrigley Field. I shake my fist after that first strike. After the second I point my bat at these bellerin’ bleachers—right where I aim to park the ball. Root throws it and I hit that fucken ball on the nose, right over the fence for two fucken runs. ‘How do you like

those apples, you fucken bastard?’ I yell at Root as I run toward first. By the time I reach home I’m almost fallin’ down I’m laughing so fucken hard—and that’s how it happened.”

Montville notes that Ruth’s memory was not perfect: The count was 2–2, not 0–2, and there was no one on base. Mrs. Lippmann and her spouse quickly left the party, and Rice asked Ruth, “Why’d you use that language?” Ruth replied, “You heard her ask me what happened. So I told her.”

Montville offers a further bit of evidence that

something

special happened in Game 3 to make the Cubs irritable. Guy Bush was the Cubs’ starting pitcher in Game 4. When Ruth came to the plate in the first inning—even though there were runners on first and second and no one out and the Cubs were facing elimination from the Series—Bush used his first pitch, a fastball, to hit Ruth. But if, the day before, Ruth had pointed to center field after the second pitch from Root in the fifth inning, the third pitch probably would have come at his head. Really.

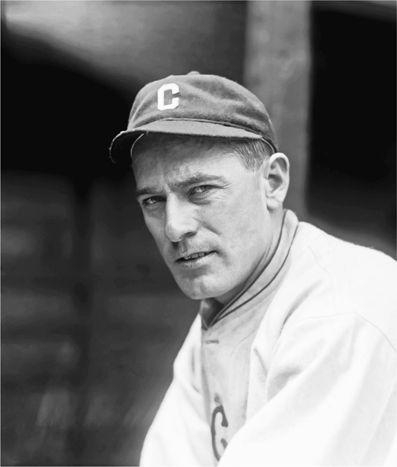

Take a long look at the hard glare coming at you from the photograph on

this page

. Does that seem like the sort of fellow who would have tolerated disrespectful behavior from anyone, even Babe Ruth? Charlie Root was a pitcher who, a Brooklyn baseball writer said, seemed to throw at Dodger hitters “for the sheer fun of it.” Because Root seemed to go through life with his chin jutting in defiance, Cubs manager Charlie Grimm nicknamed him Chinski. Root was so thoroughly not amused by the whole “called shot” story that he turned down an offer to play himself in the movie

The Babe Ruth Story

.

Charlie Root: Would Babe Ruth provoke him? (

photo credit 1.6

)

Root’s accomplishments during sixteen seasons with the Cubs rank him as the fourth-best pitcher in the team’s history, behind only Mordecai Brown, Grover Cleveland Alexander, and Ferguson Jenkins. Root holds the team record for career wins (201) and innings pitched (3,137.1). Yet he is remembered only for one pitch.

One fan at this memorable game was a twelve-year-old

named John Paul Stevens who would grow up to serve thirty-five years as a justice on the U.S. Supreme Court. At age ninety-three, in 2013, he was still a Cub fan and still convinced that Ruth did indeed point to a spot in the bleachers and hit a ball there. Stevens was also cheerfully resigned to the fact that he might be more often remembered for having been at Wrigley that day than for having been on the court all those years.

Seated along the first-base line on this myth-making day, behind the Yankees’ dugout, was the governor of New York, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who then was thirty-eight days from being elected president. FDR made the ceremonial first pitch from among the box seats. At his side was his host, Chicago’s Democratic mayor, Anton J. Cermak, the city’s only foreign-born mayor. The two were a study in contrasts.