A Peace to End all Peace (3 page)

Read A Peace to End all Peace Online

Authors: David Fromkin

AT THE CROSSROADS OF HISTORY

THE LAST DAYS OF OLD EUROPE

I

In the late spring of 1912, the graceful yacht

Enchantress

put out to sea from rainy Genoa for a Mediterranean pleasure cruise—a carefree cruise without itinerary or time-schedule. The skies brightened as she steamed south. Soon she was bathed in sunshine.

Enchantress

belonged to the British Admiralty. The accommodation aboard was as grand as that on the King’s own yacht. The crew numbered nearly a hundred and served a dozen or so guests, who had come from Britain via Paris, where they had stayed at the Ritz. Among them were the British Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith; his brilliant 25-year-old daughter Violet; the civilian head of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill; and Churchill’s small party of family members and close colleagues. In the final enchanted years before the First World War brought their world to an end, they were as privileged a group as any the world has known.

Violet Asquith kept a diary of her journey. In Pompeii she and her friends wandered “down the long lovely silent streets” that once had pulsated with the life of Imperial Rome; now, she noted, those once lively streets were overgrown with grass and vegetation.

1

In Sicily her party climbed to the ruins of an ancient Greek fortress and, amidst wild lavender and herbs, had a picnic lunch, sitting on blocks of stone from the fallen walls. Later they went higher still to watch the sunset over the sea from what remained of the old Greek theater on the heights. There they lay “among wild thyme and humming bees and watched the sea changing from blue to flame and then to cool jade green as the sun dropped into it and the stars came out.”

2

Rotations and revolutions—the heavenly movements that cause day to become night and spring/summer to become autumn/winter—were reflected in her observations of the landscape and its lighting; but a sense of the mortality of civilizations and of political powers and dominations did not overshadow Violet’s cheerful vision of her youthful voyage to the lands of antiquity. Her father presided over an empire roughly twice as large as the Roman Empire at its zenith; she may well have thought that her father’s empire would last twice as long too.

The Prime Minister, an enthusiastic sightseer, was inseparable from his Baedeker guidebook. An ardent classicist, he read and wrote with ease and pleasure in classical Greek and Latin. Winston Churchill, no scholar of ancient languages or literature, was as jealous as a child. “Those Greeks and Romans,” he protested, “they are so overrated. They only said everything

first

. I’ve said just as good things myself. But they got in before me.”

3

Violet noted that, “It was in vain that my father pointed out that the world had been going on for quite a long time before the Greeks and Romans appeared upon the scene.”

4

The Prime Minister was an intellectual, aware that the trend among historians of the ancient world was away from an exclusive concern with the European cultures of the Greeks and Romans. The American professor James Henry Breasted had won wide acceptance for the thesis that modern civilization—that is, European civilization—had its beginnings not in Greece and Rome, but in the Middle East: in Egypt and Judaea, Babylonia and Assyria, Sumer and Akkad. Civilization—whose roots stretched thousands of years into the past, into the soil of those Middle Eastern monarchies that long ago had crumbled into dust—was seen to have culminated in the global supremacy of the European peoples, their ideals, and their way of life.

In the early years of the twentieth century, when Churchill and his guests voyaged aboard the

Enchantress

, it was usual to assume that the European peoples would continue to play a dominating role in world affairs for as far ahead in time as the mind’s eye could see. It was also not uncommon to suppose that, having already accomplished most of what many regarded as the West’s historical mission—shaping the political destinies of the other peoples of the globe—they would eventually complete it. Conspicuous among the domains still to be dealt with were those of the Middle East, one of the few regions left on the planet that had not yet been socially, culturally, and politically reshaped in the image of Europe.

II

The Middle East, although it had been of great interest to western diplomats and politicians during the nineteenth century as an arena in which Great Game rivalries were played out, was of only marginal concern to them in the early years of the twentieth century when those rivalries were apparently resolved. The region had become a political backwater. It was assumed that the European powers would one day take the region in hand, but there was no longer a sense of urgency about their doing so.

Few Europeans of Churchill’s generation knew or cared what went on in the languid empires of the Ottoman Sultan or the Persian Shah. An occasional Turkish massacre of Armenians would lead to a public outcry in the West, but would evoke no more lasting concern than Russian massacres of Jews. Worldly statesmen who privately believed there was nothing to be done would go through the public motions of urging the Sultan to reform; there the matter would end. Petty intrigues at court, a corrupt officialdom, shifting tribal alliances, and a sluggish, apathetic population composed the picture that Europeans formed of the region’s affairs. There was little in the picture to cause ordinary people living in London, or Paris, or New York to believe that it affected their lives or interests. In Berlin, it is true, planners looked to the opening up of railroads and new markets in the region; but these were commercial ventures.

*

The passions that now drive troops and terrorists to kill and be killed—and that compel global attention—had not yet been aroused.

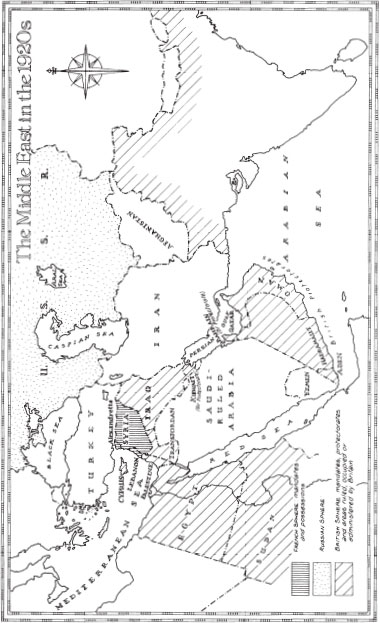

At the time, the political landscape of the Middle East looked different from that of today. Israel, Jordan, Syria, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia did not exist then. Most of the Middle East still rested, as it had for centuries, under the drowsy and negligent sway of the Ottoman Empire, a relatively tranquil domain in which history, like everything else, moved slowly.

Today, toward the close of the twentieth century, the politics of the Middle East present a completely different aspect: they are explosive. No man played a more crucial role—at times unintentionally—in giving birth to the Middle East we live with today than did Winston Churchill, who before the First World War was a rising but widely distrusted young English politician with no particular interest in Moslem Asia. A curious destiny drove Churchill and the Middle East to interfere repeatedly in one another’s political lives. This left its marks; there are frontier lines now running across the face of the Middle East that are scar-lines from those encounters with him.

THE LEGACY OF THE GREAT GAME IN ASIA

I

Churchill, Asquith, and such Cabinet colleagues as the Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George, and, later, the War Minister, Lord Kitchener, were to play a decisive role in creating the modern Middle East; but in doing so they were unable to escape from a Victorian political legacy that Asquith’s Liberal government thought it had rejected. Asquith and Grey, having turned their backs on the nineteenth-century rivalry with France and Russia in the Middle East, believed that they could walk away from it; but events were to prove them wrong.

II

The struggle for the Middle East, pitting England against European rivals, was a result of the imperial expansion ushered in by the voyages of Columbus, Vasco da Gama, Magellan, and Drake. Having discovered the sea routes in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the European powers went on to vie with one another for control of the rest of the world. England was a relatively late starter in the race, but eventually surpassed the others.

During the eighteenth century the British Isles, despite their small size, finally established an empire that encircled the globe. Like the Spaniards and the Dutch before them, the British boasted that their monarch now reigned over dominions on which the sun never set. By 1912, when Winston Churchill and Herbert Asquith cruised aboard the

Enchantress

, their monarch, George V, ruled a quarter of the land surface of the planet.

Of none of their conquests were the British more proud than those in the storied East. Yet there was irony in these triumphs; for in besting France in Asia and the Pacific, and in crowning that achievement by winning India, Britain had stretched her line of transport and communications so far that it could be cut at many points.

Napoleon Bonaparte exposed this vulnerability in 1798, when he invaded Egypt and marched on Syria—intending, he later maintained, from there to follow the path of legend and glory, past Babylon, to India. Though checked in his own plans, Napoleon afterwards persuaded the mad Czar Paul to launch the Russian army on the same path.

Britain’s response was to support the native regimes of the Middle East against European expansion. She did not desire to control the region, but to keep any other European power from doing so.

Throughout the nineteenth century, successive British governments therefore pursued a policy of propping up the tottering Islamic realms in Asia against European interference, subversion, and invasion. In doing so their principal opponent soon became the Russian Empire. Defeating Russian designs in Asia emerged as the obsessive goal of generations of British civilian and military officials. Their attempt to do so was, for them, “the Great Game,”

1

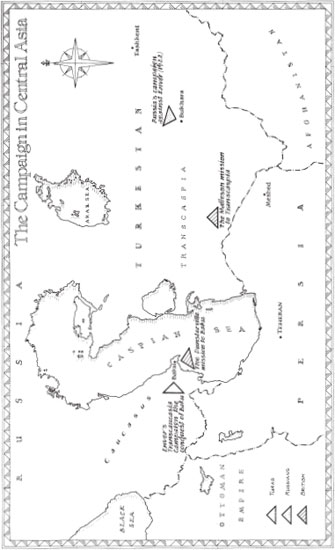

in which the stakes ran high. George Curzon, the future Viceroy of India, defined the stakes clearly: “Turkestan, Afghanistan, Transcaspia, Persia—to many these names breathe only a sense of utter remoteness…To me, I confess, they are the pieces on a chessboard upon which is being played out a game for the dominion of the world.”

2

Queen Victoria put it even more clearly: it was, she said, “a question of Russian or British supremacy in the world.”

3

III

It appears to have been a British officer named Arthur Conolly who first called it “the Great Game.” He played it gallantly, along the Himalayan frontier and in the deserts and oases of Central Asia, and lost in a terrible way: an Uzbek emir cast him for two months into a well which was filled with vermin and reptiles, and then what remained of him was brought up and beheaded. The phrase “the Great Game” was found in his papers and quoted by a historian of the First Afghan War.

4

Rudyard Kipling made it famous in his novel

Kim

, the story of an Anglo-Indian boy and his Afghan mentor foiling Russian intrigues along the highways to India.

*

The game had begun even before 1829, when the Duke of Wellington, then Prime Minister, entered into official correspondence on the subject of how best to protect India against a Russian attack through Afghanistan. The best way, it was agreed, was by keeping Russia out of Afghanistan. British strategy thereafter was to employ the decaying regimes of Islamic Asia as a gigantic buffer between British India and its route to Egypt, and the threatening Russians. This policy was associated especially with the name of Lord Palmerston, who developed it during his many years as Foreign Minister (1830–4, 1836–41, and 1846–51) and Prime Minister (1855–8 and 1859–65).

The battle to support friendly buffer regimes raged with particular intensity at the western and eastern ends of the Asian continent, where the control of dominating strategic positions was at stake. In western Asia the locus of strategic concern was Constantinople (Istanbul), the ancient Byzantium, which for centuries had dominated the crossroads of world politics. Situated above the narrow straits of the Dardanelles, it commanded both the east/west passage between Europe and Asia and the north/south passage between the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. So long as Constantinople was not in unfriendly hands, the powerful British navy could sail through the Dardanelles into the Black Sea to dominate the Russian coastline. But if the Russians were to conquer the straits they could not merely keep the British fleet from coming in; they could also send their own fleet out, into the Mediterranean, where its presence could threaten the British lifeline.

Toward the far side of the Asian continent, the locus of strategic concern was the stretch of high mountain ranges in and adjoining Afghanistan, from which invaders could pour down into the plains of British India. Britain’s aim in eastern Asia was to keep Russia from establishing any sort of presence on those dominating heights.

Sometimes as a cold war, sometimes as a hot one, the struggle between Britain and Russia raged from the Dardanelles to the Himalayas for almost a hundred years. Its outcome was something of a draw.

IV

There were vital matters at stake in Britain’s long struggle against Russia; and while some of these eventually fell by the wayside, others remained, alongside newer ones that emerged.

In 1791 Britain’s Prime Minister, William Pitt, expressed fear that the Russian Empire might be able to overthrow the European balance of power. That fear revived after Russia played a crucial role in the final defeat of Napoleon in 1814–15, but diminished again after 1856, when Russia was defeated in the Crimean War.

From 1830 onward, Lord Palmerston and his successors feared that if Russia destroyed the Ottoman Empire the scramble to pick up the pieces might lead to a major war between the European powers. That always remained a concern.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, British trade with the Ottoman Empire began to assume a major importance, and economic issues were added to the controversy, pitting free trade Britain against protectionist Russia. The deep financial involvement of France and Italy in Ottoman affairs, followed by German economic penetration, turned the area in which Russia and Britain conducted their struggle into a minefield of national economic interests.

Oil entered the picture only in the early twentieth century. But it did not play a major role in the Great Game even then, both because there were few politicians who foresaw the coming importance of oil, and because it was not then known that oil existed in the Middle East in such a great quantity. Most of Britain’s oil (more than 80 percent, before and during the First World War) came from the United States. At the time, Persia was the only significant Middle Eastern producer other than Russia, and even Persia’s output was insignificant in terms of world production. In 1913, for example, the United States produced 140 times more oil than did Persia.

5

From the beginning of the Great Game until far into the twentieth century, the most deeply felt concern of British leaders was for the safety of the road to the East. When Queen Victoria assumed the title of Empress of India in 1877 formal recognition was given to the evolution of Britain into a species of dual monarchy—the British Empire and the Empire of India. The line between them was thus a lifeline, but over it, and casting a long shadow, hung the sword of the czars.

British leaders seemed not to take into account the possibility that, in expanding southwards and eastwards, the Russians were impelled by internal historical imperatives of their own which had nothing to do with India or Britain. The czars and their ministers believed that it was their country’s destiny to conquer the south and the east, just as the Americans at the time believed it their manifest destiny to conquer the west. In each case, the dream was to fill out an entire continent from ocean to ocean. The Russian Imperial Chancellor, Prince Gorchakov, put it more or less in those terms in 1864 in a memorandum in which he set forth his goals for his country. He argued that the need for secure frontiers obliged the Russians to go on devouring the rotting regimes to their south. He pointed out that “the United States in America, France in Algiers, Holland in her colonies—all have been drawn into a course where ambition plays a smaller role than imperious necessity, and the greatest difficulty is knowing where to stop.”

6

The British feared that Russia did not know where to stop; and, as an increasingly democratic society engaged generation after generation in the conflict with despotic Russia, they eventually developed a hatred of Russia that went beyond the particular political and economic differences that divided the two countries. Britons grew to object to Russians not merely for what they did but for who they were.

At the same time, however, Liberals in and out of Parliament began to express their abhorrence of the corrupt and despotic Middle Eastern regimes that their own government supported against the Russian threat. In doing so, they struck a responsive chord in the country’s electorate. Atrocities committed by the Ottoman Empire against Christian minorities were thunderingly denounced by the Liberal leader, William Ewart Gladstone, in the 1880 election campaign in which he overthrew and replaced the Conservative Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli, Earl of Beaconsfield.

Claiming that the Sultan’s regime was “a bottomless pit of fraud and falsehood,”

7

Gladstone, in his 1880–5 administration, washed Britain’s hands of the Ottoman involvement, and the British government withdrew its protection and influence from Constantinople. The Turks, unable to stand on their own, turned therefore for support to another power, Bismarck’s Germany; and Germany took Britain’s place at the Sublime Porte.

When the Conservatives returned to office, it was too late to go back. Robert Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (Prime Minister: 1885–6, 1886–92, 1895–1900, 1900–2), aware that the Ottoman rulers were jeopardizing their own sovereignty through mismanagement, had thought of using such influence as Britain could exert to guide and, to some extent, reform the regime. Of Gladstone’s having dissipated that influence, he lamented: “They have just thrown it away into the sea, without getting anything whatever in exchange.”

8

V

Germany’s entry on the scene, at Constantinople and elsewhere, marked the beginning of a new age in world politics. The German Empire, formally created on 18 January 1871, within decades had replaced Russia as the principal threat to British interests.

In part this was because of Britain’s relative industrial decline. In the middle of the nineteenth century, Britain produced about two-thirds of the world’s coal, about half of its iron, and more than 70 percent of its steel; indeed over 40 percent of the entire world output of traded manufactured goods was produced within the British Isles at that time. Half the world’s industrial production was then British-owned, but by 1870 the figure had sunk to 32 percent, and by 1910, to 15 percent.

9

In newer and increasingly more important industries, such as chemicals and machine-tools, Germany took the lead. Even Britain’s pre-eminent position in world finance—in 1914 she held 41 percent of gross international investment

10

—was a facet of decline; British investors preferred to place their money in dynamic economies in the Americas and elsewhere abroad.

Military factors were also involved. The development of railroads radically altered the strategic balance between land power and sea power to the detriment of the latter. Sir Halford Mackinder, the prophet of geopolitics, underlined the realities of a new situation in which enemy railroad trains would speed troops and munitions directly to their destination by the straight line which constitutes the shortest distance between two points, while the British navy would sail slowly around the circumference of a continent and arrive too late. The railroad network of the German Empire made the Kaiser’s realm the most advanced military power in the world, and Britain’s precarious naval supremacy began to seem less relevant than it had been.

Walter Bagehot, editor of the influential London magazine,

The Economist

, drew the conclusion that, because of Germany, Russian expansion no longer needed to be feared: “…the old idea that Russia is already so great a power that Europe needs to be afraid of her…belongs to the pre-Germanic age.”

11

Russia’s disastrous defeat by Japan (1904–5), followed by revolutionary uprisings in St Petersburg and throughout the country in 1905, suggested that, in any event, the Czar’s armies were no longer strong enough to remain a cause for concern.

The Conservative government of Arthur James Balfour (1902–5) nonetheless continued to pursue the old rivalry as well as the new one, allying Britain not only with Japan against Russia, but also with France against Germany. But Sir Edward Grey, Foreign Secretary in the successor Liberal administration of Henry Campbell-Bannerman (1905–8), pictured the two policies as contradictory. “Russia was the ally of France,” he wrote, “we could not pursue at one and the same time a policy of agreement with France and a policy of counteralliances against Russia.”

12