A People's Tragedy (2 page)

Read A People's Tragedy Online

Authors: Orlando Figes

Although politics are never far away, this is, I suppose, a social history in the sense that its main focus is the common people. I have tried to present the major social forces —

the peasantry, the working class, the soldiers and the national minorities — as the participants in their own revolutionary drama rather than as 'victims' of the revolution.

This is not to deny that there were many victims. Nor is it to adopt the 'bottom-up'

approach so fashionable these days among the 'revisionist' historians of Soviet Russia. It would be absurd — and in Russia's case obscene — to imply that a people gets the rulers it deserves. But it is to argue that the sort of politicized 'top-down' histories of the Russian Revolution which used to be written in the Cold War era, in which the common people appeared as the passive objects of the evil machinations of the Bolsheviks, are no longer adequate. We now have a rich and growing literature, based upon research in the newly opened archives, on the social life of the Russian peasantry, the workers, the soldiers and the sailors, the provincial towns, the Cossacks and the non-Russian regions of the Empire during the revolutionary period. These monographs have given us a much more complex and convincing picture of the relationship between the party and the people than the one presented in the older 'top-down' version. They have shown that instead of a single abstract revolution imposed by the Bolsheviks on the whole of Russia, it was as often shaped by local passions and interests.

A People's Tragedy

is an attempt to synthesize this reappraisal and to push the argument one stage further. It attempts to show, as its title indicates, that what began as a people's revolution contained the seeds of its own degeneration into violence and dictatorship. The same social forces which brought about the triumph of the Bolshevik regime became its main victims.

Finally, the narrative of

A People's Tragedy

weaves between the private and the public spheres. Wherever possible, I have tried to emphasize the human aspect of its great events by listening to the voices of individual people whose lives became caught up in the storm. Their diaries, letters and other private writings feature prominently in this book. More substantially, the personal histories of several figures have been interwoven through the narrative. Some of these figures are well known (Maxim Gorky, General Brusilov and Prince Lvov), while others are unknown even to historians (the peasant reformer Sergei Semenov and the soldier-commissar Dmitry Os'kin). But all of them had hopes and aspirations, fears and disappointments, that were typical of the revolutionary experience as a whole. In following the fortunes of these figures, my aim has been to convey the chaos of these years, as it must have been felt by ordinary men and women. I have tried to present the revolution not as a march of abstract social forces and ideologies but as a human event of complicated individual tragedies. It was a story, by and large, of people, like the figures in this book, setting out with high ideals to achieve one thing, only to find out later that the outcome was quite different. This, again, is why I chose to call the book

A People's Tragedy.

For it is not just about the tragic turning-point in the history of a people. It is also about the ways in which the tragedy of the revolution engulfed the destinies of those who lived through it.

* * * This book has taken over six years to write and it owes a great debt to many people.

Above all, I must thank Stephanie Palmer, who has had to endure far more in the way of selfish office hours, weekends and holidays spoilt by homework and generally impossible behaviour by her husband than she had any right to expect. In return I received from her love and support in much greater measure than I deserved. Stephanie looked after me through the dark years of debilitating illness in the early stages of this book, and, in addition to her own heavy work burdens, took on more than her fair share of child-care for our daughters, Lydia and Alice, after they were born in 1993. I dedicate this book to her in gratitude.

Neil Belton at Jonathan Cape has played a huge part in the writing of this book. Neil is any writer's dream of an editor. He read every chapter in every draft, and commented on them in long and detailed letters of the finest prose. His criticisms were always on the mark, his knowledge of the subject constantly surprising, and his enthusiasm was inspiring. If there is any one reader to whom this book is addressed, it is to him.

The second draft was also read by Boris Kolonitskii during the course of our various meetings in Cambridge and St Petersburg. I am very grateful to him for his many comments, all of which resulted in improvements to the text, and hope that, although it has so far been one-sided, this may be the start of a lasting intellectual partnership.

I owe a great debt to two amazing women. One is my mother, Eva Figes, a past master of the art of narrative who always gave me good advice on how to practise it. The other is my agent, Deborah Rogers, who did me a great service in brokering the marriage with Cape.

At Cape two other people merit special thanks. Dan Franklin navigated the book through its final stages with sensitivity and intelligence. And Liz Cowen went through the whole text line by line suggesting improvements with meticulous care. I am deeply grateful to them both.

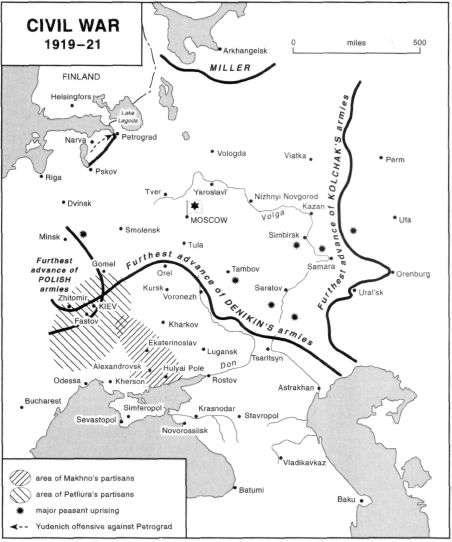

For their assistance in the preparation of the final text I should also like to thank Claire Farrimond, who helped to check the notes, and Laura Pieters Cordy, who worked overtime to enter the corrections to the text. Thanks are also due to Ian Agnew, who drew the splendid maps.

The past six years have been an exciting time for historical research in Russia. I should like to thank the staff of the many Russian archives and libraries in which the research for this book was completed. I owe a great debt to the knowledge and advice of far too many archivists to name individually, but the one exception is Vladimir Barakhov, Director of the Gorky Archive, who was more than generous with his time.

Many institutions have helped me in the research for this book. I am grateful to the British Academy, the Leverhulme Trust, and — although the Fellowship could not be taken up — to the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington for their generous support.

My own Cambridge college, Trinity, which is as generous as it is rich, has also been of enormous assistance, giving me both grants and study leave. Among the Holy and Undivided Fellows of the college special thanks are due to my teaching colleagues, Boyd Hilton and John Lonsdale, for covering for me in my frequent absences; to the inimitable Anil Seal for being a supporter; and, above all, to Raj Chandavarkar, for being such a clever critic and loyal friend. Finally, in the History Faculty, I am, as always, grateful to Quentin Skinner for his efforts on my behalf.

The best thing about Cambridge University is the quality of its students, and in the course of the past six years I have had the privilege of teaching some of the brightest in my special subject on the Russian Revolution. This book is in no small measure the result of that experience. Many were the occasions when I rushed back from the lecture hall to write down the ideas I had picked up from discussions with my students. If they cannot be acknowledged in the notes, then I only hope that those who read this book will take it as a tribute of my gratitude to them.

Cambridge November 1995

Glossary

ataman

Cossack chieftain

Black

extremist right-wing paramilitary groups and proto-parties (for the Hundreds

origin of the term see page 196)

Bund

Jewish social democratic organization

burzhooi

popular term for a bourgeois or other social enemy (see page 523) Soviet secret police 1917—22 (later transformed into the OGPU, the NKVD and the KGB); the Cheka's full title was the All-Russian Cheka

Extraordinary Commission for Struggle against Counter-Revolution and Sabotage

socialist supporters of the war campaign (1914—18) for national Defensists

defence; the Menshevik and SR parties were split between Defensists and Internationalists

desyatina

measurement of land area, equivalent to 1.09 hectares or 2.7 acres the state Duma was the elected lower house of the Russian parliament Duma

1906—17; the municipal dumas were elected town councils

guberniia

province (subdivided into uezdy and volosti)

socialists opposed to the war campaign (1914—18) who campaigned for immediate peace through international socialist collaboration; the Internationalists Menshevik and SR parties were split between Defensists and Internationalists

Kadets

Constitutional Democratic Party

kolkhoz

collective farm

anti-Bolshevik government established in Samara during the summer Komuch

of 1918; its full title was the Committee of Members of the Constituent Assembly

Krug

Cossack assembly

kulak

capitalist peasant (see page 91)

mix

village commune

NEP

New Economic Policy (1921-9)

obshchina

peasant land commune

Octobrists liberal-conservative political party

pud

measurement of weight, equivalent to 16.38 kg

Social Democrats: Marxist party (known in full as the Russian Social SDs

Democratic Labour Party); split into Menshevik and Bolshevik factions after 1903

skhod

communal or village assembly

sovkhoz

Soviet farm

Socialist Revolutionaries: non-Marxist revolutionary party (PSR); split into SRs

Right and Left SRs during 1917

Stavka

army headquarters

uezd

district (sub-division of

guberniia)

versta

measurement of distance, equivalent to 0.66 miles

voisko

Cossack self-governing community

volia

freedom; autonomy

rural township and basic administrative unit usually comprising several volost

villages

elected assembly of local government dominated by the gentry at the zemstvo provincial and district level (1864—1917); a volost-level zemstvo was finally established in 1917 but was soon supplanted by the Soviets.

Note on Dates

Until February 1918 Russia adhered to the Julian (Old Style) calendar, which ran thirteen days behind the Gregorian (New Style) calendar in use in Western Europe. The Soviet government switched to the New Style calendar at midnight on 31 January 1918: the next day was declared 14 February. Dates relating to domestic events are given in the Old Style up until 31 January 1918; and in the New Style after that. Dates relating to international events (e.g. diplomatic negotiations and military battles in the First World War) are given in the New Style throughout the book.

NB The term 'the Ukraine' has been used throughout this book, rather than the currently correct but ahistorical 'Ukraine'.

Maps

[hand]

Gorky's house

1 Russian Renault factory

2 New Lessner factory

3 Moscow Regiment

4 Erickson factory

5 First Machine-Gun Regiment

6 Bolshevik headquarters, Vyborg District

7 Kresty Prison

8 Cirque Moderne

9 Kshesinskaya Mansion

10 Arsenal

11 Peter and Paul Fortress

12 Stock Exchange

13 Petersburg University

14

Aurora

15 Finland Regiment

16 Central telegraph office

17 Petrograd telegraph agency

18 Post office

19 War Ministry

20 Admiralty

21 Palace Square

22 St Isaac's Cathedral

23 General Staff headquarters

24 Petrograd telephone station

25 Winter Palace

26

Pravda

editorial offices and printing plant 27 Pavlovsky Regiment

28 Mars Field

29 Kazan Cathedral

30 City Duma

31 State Bank

32 Marinsky Palace

33 Lithuanian Regiment

34 Preobrazhensky Regiment

35 Volynsky Regiment

36 Tauride Palace

37 Smolny Institute

38 Znamenskaya Square

39 Semenovsky Regiment

40 Petrograd electric station

41 Petrograd Regiment

42 Putilov factory

Part One

RUSSIA UNDER THE OLD REGIME

I The Dynasty

i The Tsar and His People

On a wet and windy morning in February 1913 St Petersburg celebrated three hundred years of Romanov rule over Russia. People had been talking about the great event for weeks, and everyone agreed that nothing quite so splendid would ever be seen again in their lifetimes. The majestic power of the dynasty would be displayed, as never before, in an extravaganza of pageantry. As the jubilee approached, dignitaries from far-flung parts of the Russian Empire filled the capital's grand hotels: princes from Poland and the Baltic lands; high priests from Georgia and Armenia; mullahs and tribal chiefs from Central Asia; the Emir of Bukhara and the Khan of Khiva. The city bustled with sightseers from the provinces, and the usual well-dressed promenaders around the Winter Palace now found themselves outnumbered by the unwashed masses — peasants and workers in their tunics and caps, rag-bundled women with kerchiefs on their heads.