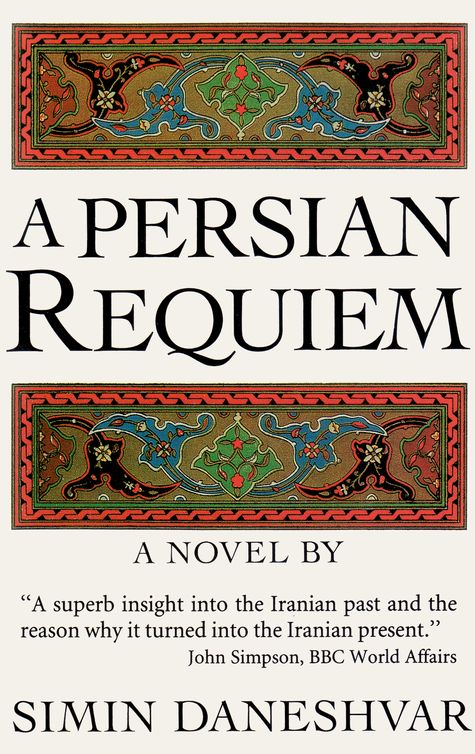

A Persian Requiem

Authors: Simin Daneshvar

A

Persian

Requiem

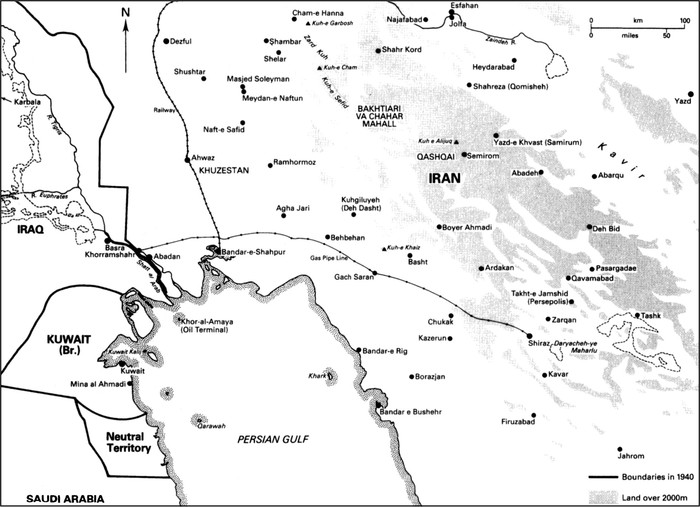

is a powerful and evocative novel. Set in the southern Persian town of Shiraz in the last years of World War II, when the British army occupied the south of Persia, the novel chronicles the life of Zari, a traditional, anxious and

superstitious

woman whose husband, Yusef, is an idealistic feudal landlord. The occupying army upsets the balance of traditional life and throws the local people into conflict. Yusef is anxious to protect those who depend upon him and will stop at nothing to do so. His brother, on the other hand, thinks nothing of exploiting his kinsmen to further his own political ambitions. Thus a web of political intrigue and hostilities is created, which slowly destroys families. In the background, tribal leaders are in open rebellion against the government, and a picture of a society torn apart by unrest emerges.

In the midst of this turbulence, normal life carries on in the beautiful courtyard of Zari’s house, in the rituals she imposes upon herself and in her attempt to keep the family safe from external events. But the corruption engendered by occupation is pervasive – some try to profit as much as possible from it, others look towards communism for hope, whilst yet others resort to opium. Finally even Zari’s attempts to maintain normal family life are shattered as disaster strikes.

An immensely moving story,

A

Persian

Requiem

is also a powerful indictment of the corrupting effects of colonization.

A

Persian

Requiem

(first published in 1969 in Iran under the title

Savushun),

was the first novel written by an Iranian woman and, sixteen reprints and half a million copies later, it remains the most widely read Persian novel. In Iran it has helped shape the ideas and attitudes of a generation in its revelation of the factors that contributed to the Islamic Revolution in 1979.

Simin Daneshvar’s

A

Persian

Requiem

… goes a long way towards deepening our understanding of Islam and the events leading up to the 1979 Revolution … The central characters adroitly reflect different Persian attitudes of the time, attitudes that were eventually to harden into support for either the Ayatollah and his Islamic fundamentalism or, alternatively, for the corrupting Westernisation of the Shah. The value of the book lies in its ability to present these emergent struggles in human terms, in the day-to-day realities of small-town life … Complex and delicately crafted, this subtle and ironic book unites reader and writer in the knowledge that human weakness, fanaticism, love and terror are not confined to any one creed.

The

Financial

Times

A

Persian

Requiem

is not just a great Iranian novel, but a world classic.

The

Independent

on

Sunday

… it would be no exaggeration to say that all of Iranian life is there.

Spare

Rib

For an English reader, there is almost an embarrassment of new settings, themes and ideas … Under the guise of something resembling a family saga – although the period covered is only a few months –

A

Persian

Requiem

teaches many lessons about a society little understood in the West.

Rachel Billington,

The

Tablet

This very human novel avoids ideological cant while revealing complex political insights, particularly in light of the 1979 Iranian revolution.

Publishers

Weekly

A

Persian

Requiem,

originally published [in Iran] in 1969, was a first novel by Iran’s first woman novelist. It has seen sixteen reprints, sold over half a million copies, and achieved the status of a classic, literally shaping the ideas of a generation. Yet when asked about the

specific appeal of the novel, most readers are at a loss to pinpoint a single, or even prominent aspect to account for this phenomenal success. Is it the uniquely feminine perspective, allowing the reader to travel freely between the microcosm of the family and the larger framework of society? Is it the actual plot which mimics so presciently the events of the Islamic Revolution? Or does it lie in the deftly woven anecdotes and fragments which add up to a descriptive whole? It is each and all of these, and perhaps more.

Feminist

Review

Daneshvar offers a fascinating, detailed view of what seems to Western eyes the complicated, rarified world of Iranian culture.

Belles

Lettres

In addition to being an important literary document of historical events, [

A

Persian

Requiem

]

represents a pioneering attempt to probe the multi-faceted aspects of Iranian womanhood in a period of great social and political upheaval.

San

Francisco

Review

of

Books

Daneshvar combines creative vision with an exceptional talent for conveying atmosphere to give a powerful portrait of the struggles and dilemmas of ordinary individuals caught in the maelstrom of war and occupation.

Middle

East

International

This is a colourful and accurate portrayal of Persian character and spirit, a beautifully evoked picture of traditional life in times of upheaval. Its popularity in Iran is eloquent of Persian perceptions not only of themselves but also of the role of the British in their country. Roxane Zand is to be thanked for giving the English reader the chance to enjoy this sensitive and important novel.

British

Journal

of

Middle

Eastern

Studies

A powerful portrait of a bygone era of Iranian social history.

The

Jerusalem

Post

“…a revelation of freshness and vivacity…”

Anita Desai

“Not to be missed.”

Shusha Guppy

“Beautifully translated, and many-layered,

A Persian Requiem

challenges convention, of east and west.”

Fred Halliday

“…a great work by a great Persian writer.”

Han Suyin

R

EQUIEM

A Novel by

Simin Daneshvar

Translated by

Roxane Zand

Roxane Zand was born in Tehran. She studied Comparative

Literature

at Harvard University, and Social History at Oxford University. She takes a strong interest in women’s issues.

I would like to thank the following for their generous help and involvement with this translation, ever since it was first undertaken, and throughout the many years it collected dust or met with misadventure: Dr. John Gurney, Keyvan Mahjour, Mohsen Ashtiani, the late Dr. Hamid Enayat, Aamer Hussein, Iradj Bagherzade and Ali Gheissari.

A special thanks to Simin Daneshvar whose place in our hearts extends beyond that of artist and humanist to a particular kind of inspiration. My gratitude for her patience and loyal support.

Finally, my love and thanks to Hamid who has journeyed with me through this book, and to my sons, Vahid and Karim.

This translation is dedicated to the memory of Amou Sarrafi, who first introduced me to it in 1969.

Roxane Zand

I

t was the wedding day of the Governor’s daughter. The Shirazi bakers had got together to bake an impressive sangak loaf, the likes of which had never been seen before.

Groups of guests filed into the marriage room just to admire the bread. Zari Khanom and Yusef Khan also managed to see it close up. The minute Yusef set eyes on it, he blurted out loud: “Those fools! Licking the boots that kick them! And to waste so much at a time like this …”

The guests nearby who overheard Yusef first edged away and then left the room. Zari, suppressing her admiration, caught Yusef’s hand and implored him, “For God’s sake, Yusef, don’t talk like that, not tonight.”

Yusef laughed at his wife. He always tried to laugh her off. His full, well-defined lips parted to reveal teeth which had once

sparkled

, but were now yellow from pipe-smoking. Then he left, but Zari stayed behind to gaze at the bread. Bending over, she lifted the hand-printed calico tablecloth to reveal an improvised table made of two old doors. All around the table were trays of wild rue arranged in flowery patterns and pairs of lovers. And in the centre was the bread, baked the colour of burnished copper. A poppy-seed inscription read: “Presented by the Bakers’ Guild to our honourable Governor” with “congratulations” written all around the edge.

“Where on earth did they find an oven big enough to bake it?” Zari wondered silently. “How much flour did it take? Yusef’s right—what a time for all this! A time when a loaf like that would make supper for a whole family, when getting bread from the bakery is a major feat. Only recently there was a rumour in town that the Governor had threatened to throw a baker into his own oven as an example to others because everyone who had eaten his

bread had come down with stomach cramps and vomiting. They said the bread was black as ink from all the dirt and scraps mixed in it. But then, as Yusef says, how can you blame the bakers? All the town’s provisions—from wheat to onions—have been bought up by the occupying army. And now … how on earth do I cover up for what Yusef has just said?”

Suddenly a voice broke into her thoughts.

“Salaam.”

She looked up and saw the English missionary doctor, Khanom Hakim, standing in front of her with Captain Singer. They shook hands with her. Both spoke only broken Persian.

“How are being the twins?” Khanom Hakim asked, adding to Captain Singer in the same clumsy language, “All of her three children being delivered by me.”

“I did not doubt it,” replied Captain Singer.

Turning back to Zari, she asked, “The babies’ dummy still being used?” Struggling through a few more sentences in Persian, she finally tired of it and carried on in English. But Zari was too distracted to understand, even though she had studied at the English school and her late father was considered the best English teacher in town.

It was really Singer who captured her attention, and although Zari had heard about his transformation, she refused to believe it until she saw him with her own eyes. The present Captain Singer was none other than Mr Singer, the sewing machine salesman who had come to Shiraz seventeen years ago, and who treated anyone buying his sewing machines to ten free sewing lessons delivered by himself in his barely understandable Persian. He would squeeze his enormous bulk behind the sewing machine and teach the girls of Shiraz embroidery, lattice-work and pleating. It was a wonder he didn’t laugh at the ridiculous figure he cut. But the girls, including Zari, learned well.

Zari had been told that overnight, as soon as war broke out, Mr Singer had donned a military uniform, complete with badges of rank. Now she could see that it really suited him. It must have taken a lot, she thought, to live as an impostor for seventeen years. To have a fake job, fake clothes—to be a fraud in every respect. But what an expert he had been! How cunningly he had persuaded Zari’s mother to buy a sewing machine—Zari’s mother, whose sole fortune was her husband’s modest pension. Mr Singer had told her

that all a young woman needed for her dowry was a Singer sewing machine. He had claimed that the owner of a sewing machine could always earn her own living, and had said that all the leading families in town had bought one from him for their daughters’ dowry; as proof, he had produced a notebook containing a list of his influential customers.

At this moment, three Scottish officers, wearing kilts and what seemed like women’s knee-length socks, broke Zari’s train of thoughts as they came forward to join them. Behind them came McMahon, the Irishman, who was Yusef’s friend. McMahon was a war correspondent and always carried a camera. He greeted Zari and asked her to tell him all about the wedding ceremony.

Willingly

she described all the details of the vase, the candlesticks, the silver mirror, and the reasons for the shawl, the ring wrapped in silk brocade and the symbolic meaning of the bread and cheese, the herbs and the wild rue.

Two large sugar cones, made at the Marvdasht Sugar Refinery especially for the wedding, were placed one at either end of the ceremonial table. One cone was decorated as a bride and the other as a groom, complete with top hat. In one corner of the room stood a baby’s pram lined in pink satin and piled high with coins and sugar-plums. Zari pulled back the silk brocade cloth covering the traditional saddle and explained to McMahon, “The bride sits on this so she can dominate her husband forever.”

A few people around them chuckled loudly and McMahon clicked away busily with his camera.

Just then, Zari’s glance fell on Gilan Taj, the Governor’s younger daughter, who seemed to be beckoning to her. She excused herself and went over to the young girl. Gilan Taj was no more than ten or eleven, the same age as Zari’s own son, with honey-coloured eyes and sleek, brown shoulder-length hair. She was wearing ankle socks and a short skirt.

“Mother says would you please lend her your earrings,” Gilan Taj asked Zari. “She wants the bride to wear them just for tonight. They’ll be returned to you first thing tomorrow morning. It’s Khanom Ezzat-ud-Dowleh’s fault for bringing a length of green silk for the bride to put around her shoulders. She says it will bring good luck, but my sister isn’t wearing anything green to match it.” The young girl could have been repeating a lesson by heart.

Zari was dumb-struck. When had they spotted her emerald

earrings

,

let alone made plans for getting their clutches on them? In all the bustle, who could have spared the time to fuss over such minor details of the bride’s dress? She said to herself, “I bet it was that woman Ezzat-ud-Dowleh’s doing. Those beady eyes of hers

constantly

keep track of what everyone has.” Aloud she replied

nervously

, “Those were a wedding present—a special gift from Yusef’s poor mother.”

Her mind flashed back to that night in the bridal chamber when Yusef had put the earrings on her himself. He was sweating

profusely

, and in all the hustle and bustle he had groped nervously under the women’s scrutiny to find the small holes in her earlobes.

“They’re playing the wedding tune,” Gilan Taj prompted. “Please hurry. Tomorrow morning then …”

Zari took off the earrings.

“Be very careful,” she warned, “make sure the drops don’t come off.” In her heart she knew that the likelihood of ever seeing those earrings again was very remote indeed. Yet how could she refuse?

At this point the bride entered on Ezzat-ud-Dowleh’s arm. “Yes,” thought Zari, “that woman is never slow to become confidante and busybody to every new governor of the town.” The bride was followed by five little girls each carrying a posy of flowers and wearing frilly dresses, and five boys in suits and ties. The room was now full, and the ladies started to clap. The British officers who were still there quickly followed suit. Clearly all the pomp and formality was for their benefit, but to Zari the wedding march seemed more like a mournful procession out of a Tazieh passion play.

The bride sat on the saddle, in front of the silver mirror and Ezzat-ud-Dowleh rubbed the sugar cones together over her head to ensure sweetness in the marriage. Then a woman holding a needle and red thread pretended to sew up the tongues of the groom’s relatives. This raised a loud guffaw from the British officers. Next, a black nursemaid carrying a brazier of smoking incense suddenly appeared out of nowhere like a genie.

“All the villains of the Ta’zieh are here,” Zari mused to herself. “Marhab, Shemr and Yazid, the farangi, the unwanted Zeynab, the rapacious Hend, Aysheh, and last but not least Fezza!” And for an instant it occurred to her that she was thinking just like Yusef.

The crowded room was noisy and stifling. The smell of incense mixed with the strong scent of tuberoses, carnations and gladioli

which were displayed in large silver vases around the room but glimpsed only from time to time between the whirl of the ladies’ dresses.

Zari missed the moment when the bride gave her consent.

Suddenly

she felt a hand on her arm.

“Mother is very grateful,” whispered Gilan Taj; “they really suit her …”

The rest of her sentence was drowned in the commotion and blare of military music which followed the wedding tune. A booming which pulsated like the beating of battle drums …

Now it was Ferdows, the wife of Ezzat-ud-Dowleh’s manservant, who came in, threading her way past the guests to give her mistress her handbag. Ezzat-ud-Dowleh took out a pouch full of

sugar-plums

and coins which she showered over the bride’s head. To save the foreign officers the trouble of scrambling for a coin, she handed one to each of them and one to Khanom Hakim. Until that moment Zari had not seen Ezzat-ud-Dowleh’s son, Hamid Khan, in the wedding room, but she noticed him now speaking to the British officers.

“My dear mother has the Midas touch!” she heard him saying. Turning to her abruptly, he said, “Zari Khanom, please translate for them.”

Zari ignored him.

“Not on your life!” she retorted silently. “My former suitor! I had more than enough of you and your ways that time when our history teacher took us sixteen-year-old girls to your home on the pretext of visiting an eighteenth-century house. You looked us over with your lecherous eyes, supposedly showing us the baths and the Zurkhaneh, boasting that your ancestor, the famous Sheriff, built the hall of mirrors and that Lutf-Ali Khan had done the painting on the mirrors. And then your mother had the nerve to come to the Shapuri public baths on our usual bath-day and barge her way into our cubicle just so she could size up my naked body. It was lucky Yusef had already asked for my hand, otherwise my mother and brother might well have been taken in by your extravagant

life-style

.”

The ceremony over, celebrations got under way in the garden and on the front verandah. All the cypresses, palms and orange trees had been strung with light bulbs—each tree a different colour. Large bulbs lit the larger trees, while small ones had been used for

the smaller, twinkling like so many stars. Water flowed from two directions in a terraced stream into a pool, cascading over the red glow of rose-shaped lamps set inside each step. The main part of the garden had been spread with carpets for dancing. Zari assumed the wiring for the waterfall lights ran under the carpets. Around the edge of the pool they had alternated bowls full of different kinds of fruit, three-branched candlelabra and baskets of flowers. If a gust of wind blew out one of the candles, a servant would instantly relight it with a short-stemmed taper.

The Governor, a tall, heavy-set man with white hair and a white moustache, was standing by the pool welcoming even more guests. An English Colonel with a squint, walking arm in arm with Zari’s former headmistress, was the last to arrive. Behind them came two Indian soldiers carrying a basket of carnations in the shape of a ship. When they reached the Governor, they placed it at his feet. At first the Governor didn’t notice the flowers as he was busy kissing the English-woman’s hand. But the headmistress must have drawn his attention to them because the Governor shook hands with the Colonel again before extending his hand to the Indian soldiers. They, for their part, merely clicked their heels together, saluted, about-turned, and withdrew.

Then came the hired musicians. One played the zither, while his plump friend accompanied him on the tar and an attractive young boy sang a song. When the song was over, there was a dance followed by another song. The musicians then changed to a

rhythmic

beat and a group of men and women dressed as Qashqais did a sort of tribal dance. Zari had seen a lot of fake things in her time, but never fake Qashqais!

Now it was the turn of the hired musicians brought over especially from Tehran. The noises sounded confused to Zari; even the sight of all those dishes piled high with sweets and dried fruit and nuts nauseated her. The sweets had probably been sent by the Confectioners’ Guild and the fruit and the nuts by the Grocers’ Guild, she thought cynically. The five-tiered wedding cake flown in by air had, she knew, been presented by the Supreme Command of the foreign armed forces. They had displayed it on a table on the verandah. On the top tier stood a bride and groom hand in hand, with a British flag behind them, each crafted skilfully out of icing.

To Zari it felt like watching a film. Especially with the foreign army in full regalia: Scottish officers in kilts, Indian officers in

turbans … If she hadn’t lost her earrings, thought Zari, it would have been possible to sit back and enjoy the show.

The bride and groom led the dancing. The bride’s long train with its glittering rhinestones, sequins and pearls swept over the carpet like a trail of shooting stars. She was no longer wearing the length of green silk or her bridal veil, but the earrings were still there. The British Colonel had one dance with the bride; so did Captain Singer, in whose large arms the bride skipped about like a grasshopper. He even trod on her toes several times.

Then the foreign officers sought out the other ladies. The Shirazi women in their colourful dresses danced in the arms of strangers while their men, perched on the edge of their seats, kept a nervous eye on them. Some of the men seemed particularly restless and agitated. Was it the light-hearted tempo of the music, or an inner fire kindled at the sight of strangers holding their wives so closely? It was impossible to know. At the end of the dance the officers carefully returned the ladies to their chairs, as if they were incapable of finding their own way back. They clicked their heels and kissed the lady’s hand, at which the woman’s own escort would nearly jump out of his seat and then settle back to try to compose himself. Not unlike a jack-in-the-box. The only person who didn’t dance was McMahon. He took pictures instead.