A Place Beyond Courage (2 page)

1

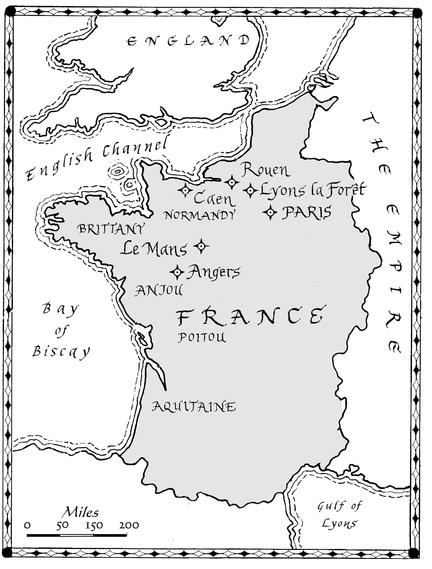

Vernon-sur-Seine, Normandy, Autumn 1130

‘Why,’ John FitzGilbert asked with icy displeasure, ‘does the list say palfreys when the beasts I’ve just seen in the stables are common nags?’ He cast his deputy a penetrating look from eyes the hue of shadowed water.

‘My lord?’ A muscle ticked in the fleshy pouch beneath the man’s left eye.

Tresses of autumn sunlight swept across the rushes carpeting the great hall of King Henry’s hunting lodge and trailed the edge of a trestle table, illuminating the lower third of a parchment covered in a scribe’s swift scrawl. A strand of gold touched the back of John’s hand and twinkled on the braid cuffing his tunic. ‘One’s spavined, another’s got mange and the chestnut’s old enough to have carried Moses out of Egypt!’ He stabbed a forefinger at the offending entry on the exchequer roll. ‘It says here that Walter Picot renders five palfreys in payment of his debt to the King. If those creatures out there are palfreys, I’ll salt my boots and eat them.’

‘My lord, I—’

‘No excuses, Ralph. Return these sorry beasts to Picot and make him replace them with others fit to the description. If he refuses, report to me and I will deal with him. I’m not in the habit of giving house room to other men’s leavings.’ Leaning back from the table, he laid his hand to his sword hilt in deliberate emphasis. As King Henry’s marshal, he was responsible for discipline in the hall and a sword was part of his daily apparel rather than an accoutrement of ceremony and war. ‘Of course,’ he added, rubbing a reflective thumb over the smooth curve of the pommel, ‘if I find out that Walter supplied five good palfreys and someone has been using my absence from court to line his own purse by switching them for nags . . .’ He let the sentence hang unfinished.

Ralph licked his lips. ‘I am sure it is not the case, my lord.’

John raised a sceptical eyebrow. Leaning forward again, he placed his hand upon the parchment, arching long fingers over the words. ‘I expect absolute loyalty and competence from my men and I reward it generously. Play me false or let me down and I will find out - and if you live to regret it, you will be unfortunate. Understood?’ John was barely five and twenty, but had won the right to be the King’s marshal by more than heredity. Three years ago, he had defended a challenge to his position in trial by combat and settled the matter so convincingly that no one had questioned his abilities to fight or administrate since.

‘My lord, I will attend to the matter,’ Ralph answered, pale and set-lipped.

‘See that you do.’ John picked up the parchment and studied the next entry concerning quantities of bread for feeding the royal hounds. Usually he would have delegated the scrutiny of such lists to a subordinate but having been absent from court dealing with personal matters of estate in the wake of his father’s death, he needed to stamp his authority on his office like a seal impressing warm wax.

‘Christ, how much bread does a dog—?’ He stopped and looked up as a shadow blocked his light. ‘My lord?’

‘Never mind that,’ said Robert FitzRoy, Earl of Gloucester, standing over the trestle, arms folded, the sun streak now warming his blood-red tunic. ‘Come outside. There’s something you need to see.’

John mentally sighed. It was pointless telling Gloucester he wanted to finish assessing these accounts before he went anywhere. As the King’s eldest son, albeit bastard born, Gloucester wielded a powerful influence at court. It was in John’s interests to be accommodating; besides, the man was a friend, ally and sponsor.

He pushed to his feet. Gloucester was tall, but John topped him by the length of an index finger, although the Earl’s broader frame made them look much of a size. John picked his hat off the board and tucked it through his belt, thereby conceding he was unlikely to return to his accounts this side of the dinner hour.

‘My cousin Stephen has a new horse.’

Pinning his cloak, John stepped around the trestle. ‘Take those tallies to my chamber,’ he commanded over his shoulder to Ralph, ‘and I want to see the military service receipts for the months I’ve been gone. I’ll expect a report on what’s been done about that walking dog meat in the stables before noon tomorrow.’

‘Yes, my lord.’ His deputy bowed, sweat beading his brow.

John quickened his pace to catch up with Robert, his stride long and confident.

‘They know you’re back,’ the latter remarked with amusement.

Mordant humour curved John’s lips. ‘They had better do.’

‘You’ve found foul deeds hidden in the murk?’

John’s smile deepened, putting creases in his cheeks, showing where one day harder lines would develop. ‘Not as yet. Some questionable horses and dogs that appear to be eating best wheaten bread in suspicious quantities, but nothing I cannot handle.’

‘And the women?’

‘Nothing I cannot handle there either,’ John said casually.

Robert laughed aloud and set his arm across John’s shoulders. ‘I should hope not. Ah, it’s good to have you back!’

The courtyard was a churn of noisy, organised chaos, signalling the imminent departure of the hunt. Amid misty clouds of breath and pungent aromas of horse and stable, nobles were mounting up or conversing in groups as they waited for their grooms. Dogs snuffled underfoot, or, quivering with anticipation, strained on taut leashes. John observed the rib-serrated flanks of a white gazehound and thought about the accounts he had just been reading.

A crowd had gathered to watch a ruddy fair-haired man putting a powerful roan stallion through its paces. Robert and John joined the group and stood with arms folded to watch the performance.

‘Spanish,’ John said with an appreciative eye and felt a twinge of envy. As the King’s marshal, he owned fine horses himself but a beast of this calibre was too rich for his purse. However, it was standard fare for Stephen, Count of Mortain, King Henry’s nephew and so high in favour that he was flying above most other folk at court. Not that Stephen was haughty with other men because of it. John had heard Henry’s daughter, the Empress Matilda, remark with contempt that Stephen would drink water with the horses like a common groom rather than quaff wine out of a precious goblet as a man of his rank ought to do.

Stephen made the horse rear and paw the air. A broad grin lit up his face and his eyes sparkled with pleasure. He brought the roan down to all fours and dismounted but only to spring back into the saddle facing backwards. Then he scissored round to the fore and swept a flourish to his appreciative audience. He was so exuberant that it was impossible not to be caught up in his high spirits and John began to laugh and then applaud with the rest of the crowd.

Gloucester cupped his hands to shout at Stephen, ‘Have you ever thought of performing such tricks for a living?’

John glanced sidelong at the Earl, noting that his mirth was tinged with asperity. There was an edge of rivalry between Gloucester and his cousin Stephen. Both were magnates; both were close kin to the King. All the time they were slapping each other’s backs and drinking together in the hall they were jostling for position and favour.

‘Many times!’ Stephen called back cheerfully. He gathered the reins and settled the horse, patting its neck, tugging its ears. ‘But then I would lose the joy.’

‘John has to earn his crust keeping the court concubines in order. I haven’t seen any diminishing in his enthusiasm for the task, and it involves just as much sleight in the saddle as yours!’ Robert retorted.

Stephen gave a knowing grin. ‘I wouldn’t dare to compete with the anvils and hammers of a royal marshal on that score!’ he quipped, to the laughter of all, for everyone knew these were the time-honoured symbols of a marshal as well as a euphemism for the male reproductive equipment. John’s reputation in the latter department was somewhat notorious and he did nothing to play it down. Now he merely flourished a sardonic bow.

Stephen’s attention focused on a point beyond his audience. ‘The King is here,’ he said. ‘Best mount up or you’ll be left behind.’ He nudged the roan towards a stocky, grizzle-haired man who had emerged from one of the lodging halls and was setting his foot to the stirrup of a handsome bay. A heavy gold clasp pinned his short hunting cloak at his shoulder. Two swaggering young men - Robert de Beaumont, Earl of Leicester, and his twin brother Waleran, Count of Meulan - accompanied him. They were cronies of Stephen and treated with suspicion by Robert of Gloucester because of their intimacy with his father the King. Meulan had proved a traitor in the past, but the King had forgiven him his transgressions and welcomed him back at court. Beaumont, the more circumspect of the two, cast an observant glance around as he took his courser’s reins from a groom. John thoughtfully assessed their proximity to Henry. This was another area where he needed to focus following his absence. Every subtle change and nuance had to be taken into account in order to survive and advance at court.

Stephen greeted them all with natural bonhomie. John thought - with further admiration for the Count of Mortain - that such ebullience was also a way of opening doors and disarming men of their caution.

‘You’re riding out with us,’ Robert told John as he called up his mount and set his foot to the stirrup. ‘I’ve had your horse saddled.’ He snapped his fingers to a groom who led forward John’s freckled grey courser.

John tugged his hat from his belt and pulled it down over his blond-brown hair. ‘Thank you, my lord,’ he said with muted enthusiasm.

Robert chuckled. ‘You don’t mean it now.’ He tossed John a boar spear, which the latter caught mid-haft with a lightning reflex, ‘but you will in a while.’

Cantering along a forest trail, the first autumn leaves glimmering from the trees in flakes of sunlit amber, the ground firm but springy under the grey’s hooves, John realised Robert had been right. The powerful surge of his horse was exhilarating and the rich colours and deciduous scents of the autumn woods filled him with sensual pleasure.

The King was hunting hard, pushing his horse and the dogs to their limit, his cloak bannering out behind him and his body curled over his mount’s neck like a wave. The beaters flushed a boar from a thicket and Henry was after it like the devil in pursuit of a soul, one hand to the reins, the other hefting a spear. John spurred after him with the rest of the hunt, ducking under tree branches, forcing his way through thorny bramble thickets. The thud of hooves upon forest mulch, the belling of hounds and the hard breath of his horse were a joy to his ears. Count Stephen pushed past him on his new roan, the Beaumont twins charging behind accompanied by the King’s cup-bearer William Martel. Robert of Gloucester scoured their heels, his mouth set in grim determination. Prudently, John reined back and gave room to Henry’s constable, Brian FitzCount, lord of Wallingford. John was his deputy in the household and careful to keep on his good side. FitzCount acknowledged John’s courtesy with a flash of teeth and a fisted wave as he spurred on amid a flurry of dogs.

The hunting horn sounded to John’s left, but veering with the wind. He pivoted the grey towards it, but hastily drew on the rein and adjusted his grip on his spear as the undergrowth before him rustled with vigorous motion. An instant later three wild pigs broke from a deep thicket of bramble and ivy and charged past him so closely that his horse plunged and shied. He saw earth-smeared tushes, coarse rusty hair and the moist gleam of snouts. Controlling his mount with the grip of his knees, he grasped the spear like a javelin and cast it with all his strength, piercing one of the boars behind the left shoulder to the full depth of the iron blade. The pig leaped and fell in a thresh of limbs and deafening squeals. The spear haft snapped off, leaving a bloody stump in the wound. John drew his sword and manoeuvred the grey cautiously towards his victim. Even mortally injured, a wild boar was capable of eviscerating a dog and slashing a horse’s leg to the bone. The boar struggled to rise, failed, shuddered and was still.

As John dismounted, the forest around him filled with running dogs, beaters and huntsmen on foot. In the distance, a horn was blowing for another kill - probably acknowledging the King’s success. He gazed at his own prize and, as a dog-keeper whipped the hounds to heel and his heartbeat slowed, he suddenly grinned like a youth.

By the time the main hunt had turned back to investigate the second blowing of the mort, John was watching two beaters heave his prize across a pony’s back.

Other books

Fossil Lake: An Anthology of the Aberrant by Ramsey Campbell, Peter Rawlik, Jerrod Balzer, Mary Pletsch, John Goodrich, Scott Colbert, John Claude Smith, Ken Goldman, Doug Blakeslee

Cloneward Bound by M.E. Castle

Love Off-Limits by Whitney Lyles

Christian (Vampires in America: The Vampire Wars Book 10) by D.B. Reynolds

Elizabeth Mansfield by The GirlWith the Persian Shawl

Renegade by Souders, J.A.

Calico Cross by DeAnna Kinney

Chicken Soup for the Kid’s Soul by Jack Canfield

The Wildwater Walking Club by Claire Cook

Prince Incognito by Rachelle McCalla