A Singular Woman (18 page)

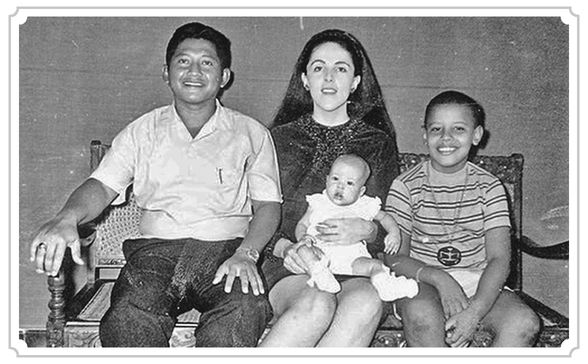

With Lolo, Maya, and Barack, 1970

The years in Jakarta had marked them all. For Ann, who would return repeatedly as an anthropologist and as a development consultant over the next twenty-five years, the experience had given her powerful insight into the lives of ordinary Indonesians that few Western advisers would ever be in a position to acquire. She would never adopt what Yang Suwan thought of as typical expatriate attitudesâacquisitiveness, arrogance, and an insistence on having the last word. She would never become one of those infatuated “Java junkies” or “Java freaks.” She had lived through a dark period in the country's history. She had lived like an Indonesian woman, worrying at times about how to feed, protect, and educate her children. As Yang put it, “She knew how to solve problems that other expatriates don't know exist.”

Barry, too, had been shaped in ways that would remain with him, for better or for worse. One colleague of Ann's in Indonesia in the late 1970s, John Raintree, who raised his two children abroad, said Ann, by the choices she made, gave Barry not one but two important experiences: First, she gave him an extraordinary adventure and the chance to be broadened and strengthened by living overseas; then, by enabling him to return to the United States and live out his teenage years there, she allowed him to begin to develop his identity as an American.

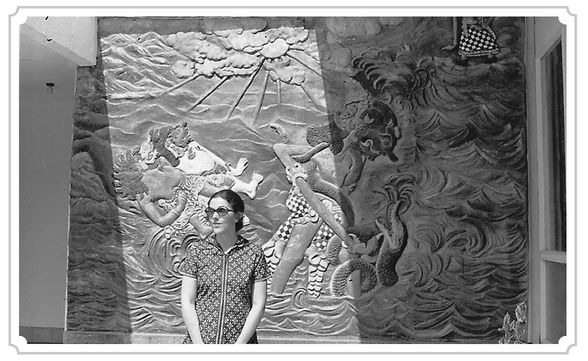

In Indonesia, June 1972

A few weeks before the presidential election in 2008, I traveled to New Haven, Connecticut, to meet Michael Dove, a professor of anthropology at Yale and a longtime friend of Ann's. Dove had spent his mid-twenties in Kalimantan, his thirties in Java and Pakistan, his forties in Hawaiiâand had known Ann in almost all of those places. Expatriate life has its advantages, he told me: It's exciting, there is boundless hope, you leave things behind. You are in limbo overseas. “I didn't know how many family problems I had until I came back from Asia,” he said. Your American values are thrown into relief, he suggested. You think about them in new ways. Dove had been thinking about the suggestion that Lolo had become more American and Ann more Javanese. “I think it's more complicated than that,” he said. “By becoming more Javanese, she was getting more insights into what it meant to be an American, both the good and the bad. Because, of course, we never become Javanese. That lies beyond us.”

Five

Trespassers Will Be Eaten

I

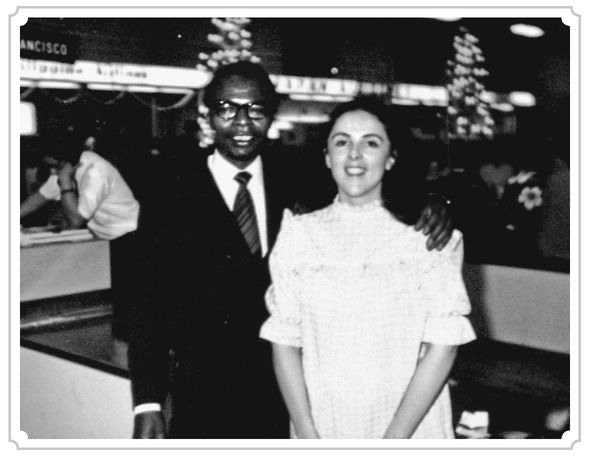

n the summer of 1973, Ann touched down on the U.S. mainland for the first time in eleven years. She was thirty years old, finishing her first year as a graduate student at the University of Hawaiâi, divorced from one husband, separated from another, a single parent of two on a five-week cross-country road trip with her children and her mother. “Pretty exhausting,” she wrote to a friend, “especially since we travelled by bus most of the way.” Stopping first in Seattle, Ann visited Jackie Farner, the only high school classmate with whom she had stayed in contact. Like Ann, Jackie had made some unorthodox life choicesâmoving to rural Alaska to teach, living in a log cabin, marrying an Aleut. On a day trip into the Cascades, Barry and Maya saw snow for the first time. Then they headed down the West Coast through California, across the desert into Arizona, and over to the Grand Canyon, then east to Kansas City and Chicago, doubling back finally through Yellowstone National Park and San Francisco en route home to Honolulu. “Actually, I was surprised how little change we saw,” Ann wrote. “More bluejeans, campers and mustaches, but the countryside around Seattle looks about the same.” In Kansas City, they bunked in the basement recreation room of Arlene Payne, Madelyn's sister, who was teaching at the University of Missouri. Jon Payne arrived from Colorado, not having seen Ann since his months on the Dunhams' couch on Mercer Island sixteen years earlier. They all spent a few days talking and playing darts, Jon venturing out into the sweltering heat to take Barry and Maya to a baseball game. Jon was struck by Ann's evident happiness, her pride in her children, the confidence she had acquired. She was, in some ways, a different person than the one he remembered. Having weathered the turbulence of the intervening yearsâpregnancy at seventeen, raising biracial children, her years in Jakartaâshe seemed to have come into her own.

n the summer of 1973, Ann touched down on the U.S. mainland for the first time in eleven years. She was thirty years old, finishing her first year as a graduate student at the University of Hawaiâi, divorced from one husband, separated from another, a single parent of two on a five-week cross-country road trip with her children and her mother. “Pretty exhausting,” she wrote to a friend, “especially since we travelled by bus most of the way.” Stopping first in Seattle, Ann visited Jackie Farner, the only high school classmate with whom she had stayed in contact. Like Ann, Jackie had made some unorthodox life choicesâmoving to rural Alaska to teach, living in a log cabin, marrying an Aleut. On a day trip into the Cascades, Barry and Maya saw snow for the first time. Then they headed down the West Coast through California, across the desert into Arizona, and over to the Grand Canyon, then east to Kansas City and Chicago, doubling back finally through Yellowstone National Park and San Francisco en route home to Honolulu. “Actually, I was surprised how little change we saw,” Ann wrote. “More bluejeans, campers and mustaches, but the countryside around Seattle looks about the same.” In Kansas City, they bunked in the basement recreation room of Arlene Payne, Madelyn's sister, who was teaching at the University of Missouri. Jon Payne arrived from Colorado, not having seen Ann since his months on the Dunhams' couch on Mercer Island sixteen years earlier. They all spent a few days talking and playing darts, Jon venturing out into the sweltering heat to take Barry and Maya to a baseball game. Jon was struck by Ann's evident happiness, her pride in her children, the confidence she had acquired. She was, in some ways, a different person than the one he remembered. Having weathered the turbulence of the intervening yearsâpregnancy at seventeen, raising biracial children, her years in Jakartaâshe seemed to have come into her own.

Back in Honolulu in early August, Ann wrote a long letter to Bill Byers, the wheelman on the fateful, Cadillac-convertible flight to the San Francisco Bay Area. She had telephoned him during the bus trip but had found him at the end of a marriage, facing the death of his father and in no mood for conversation. Her letter was humorous, unself-conscious, earthy, self-mocking, mordant, gently teasing, and emotionally direct. “If you could find it in your

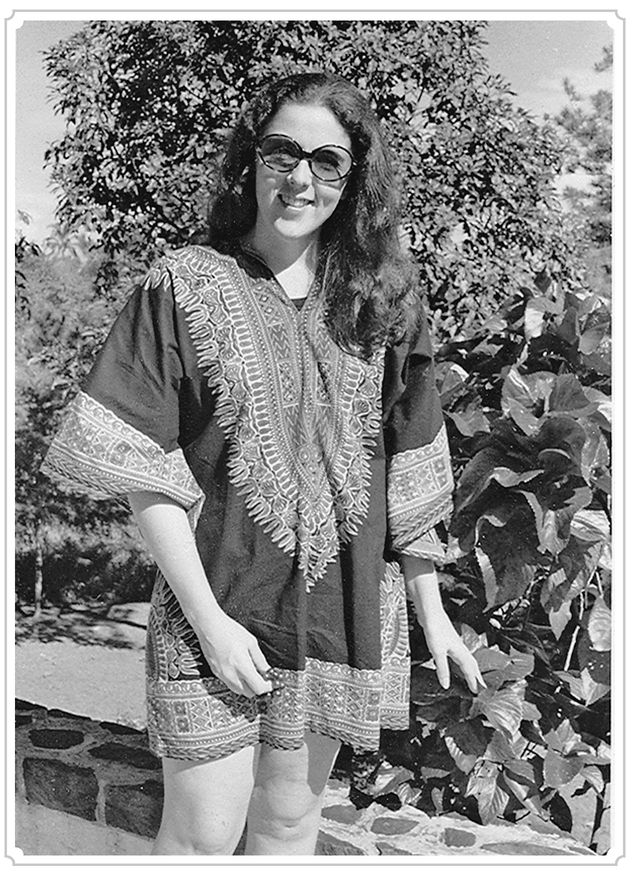

CRABBY

heart to scrawl me a note I would be overjoyed!” she wrote. “Surely, out of the last twelve years, you could sift a couple of tarnished badges to flash at me. I am not such a harsh critic after all, having screwed up royally a few times myself.” She enclosed two photographs, one of her children and one of herself, dressed in a black dashiki with bright orange trim and a pair of oversized sunglasses, her brown hair thick and loose, swept over one shoulder. “Would like one of you if you have a spare,” she scribbled in a postscript, soliciting a photo in return. “Doesn't matter if you're bald and fat or skinny and hairy. I've gained about 15 pounds in the rear since coming back from Asia too.”

CRABBY

heart to scrawl me a note I would be overjoyed!” she wrote. “Surely, out of the last twelve years, you could sift a couple of tarnished badges to flash at me. I am not such a harsh critic after all, having screwed up royally a few times myself.” She enclosed two photographs, one of her children and one of herself, dressed in a black dashiki with bright orange trim and a pair of oversized sunglasses, her brown hair thick and loose, swept over one shoulder. “Would like one of you if you have a spare,” she scribbled in a postscript, soliciting a photo in return. “Doesn't matter if you're bald and fat or skinny and hairy. I've gained about 15 pounds in the rear since coming back from Asia too.”

In Hawaii, 1973

She recounted the bus-tour itinerary, then described, with caustic amusement, a chance encounter in downtown Honolulu with a certain “rather dull, round-faced boy,” a mutual acquaintance who had gone on to some success in retail. “Fingers aglitter with diamonds and rubies, he offered me a ride in his limousine and gave me an invitation to a fashion show he was staging that afternoon,” she wrote in fluid, loopy script. “I didn't especially appreciate it since I was dressed in the baggiest most non-descript dress I own, pigtail and rubber slippers and looking very scroungy that day (I believe his exact words when he saw me were: âWell, well, just look at you!') I could have clobbered him, but it wasn't worth it (is anything?)” Recapitulating the recent events of her rather eventful life, she brushed past her second marriage. “I remarried, to an Indonesian geographer,” she wrote, then dropped the subject abruptly. She ventured a guess at her future: “Just recently I got an East-West Center grant which will carry me, albeit meagerly, through my Ph.D. plus field work, that is till the end of '75. After that, I shall be most content to spend the rest of my life, I suppose, exploring obscure topics and obscure corners of the world. Probably a useless sort of life and not very socially relevant, especially since I hate applied anthropology (neo-colonialism in bad disguiseâI had a lot of bad experiences with it in Asia). I do hope to spend

most

of my time for the next few years in the islands, since my son Barry is doing very well in school here and I hate to take him abroad again till he graduates, which won't be for another 6 years.”

most

of my time for the next few years in the islands, since my son Barry is doing very well in school here and I hate to take him abroad again till he graduates, which won't be for another 6 years.”

She had kept her earlier commitment. The year Barry returned to Honolulu and entered fifth grade at Punahou, Ann traveled nearly seven thousand miles to spend Christmas with him and her parents, leaving Lolo and Maya in Indonesia. Before she arrived, Barry was told by his grandmother that his mother had lined up an unexpected gift: Seven years after his parents had divorced, his father was coming to visit. Obama Sr. was living in Kenya, where he had moved with his third wife, an American he had met while he was at Harvard and with whom he had produced two more children. When Ann arrived, she plied Barry with information about Kenyan historyânone of which he retained, according to his account. She assured him that his father knew all about him from her letters. “âYou two will become great friends,' she decided,” Obama writes in his memoir, leaving the verb dangling dubiously off the end of the sentence. Ann had worked to keep alive the connection between Obama and his son. Her friend Kadi Warner told me, “She really was committed for him to have some presence in Barry's life. She knew it was up to her to maintain it.”

Obama's account of his father's Christmas visit is poignant. He notices the effect of his father's presence on his mother and grandparentsâhis grandfather “more vigorous and thoughtful,” his mother “more bashful.” As the weeks lurch along, tension buildsâ“my mother's mouth pinched, her eyes avoiding her parents, as we ate dinner.” After his father scolds him for wasting his time watching a cartoon special of

How the Grinch Stole Christmas!

an argument breaks out between his parents and grandparents. Ann seems to mediate at first, then sides with Obama against her parents. “I listened to my mother tell her parents that nothing ever changed with them,” the younger Obama writes. Dispatched by his grandmother the next day to collect any dirty laundry from the apartment where his father is staying, he finds his father shirtless and his mother ironing. She appears to have been crying. He delivers his message and declines an invitation to stay. Back upstairs at his grandparents' apartment, Ann appears in his room. “You shouldn't be mad at your father, Bar,” she tells him. “He loves you very much. He's just a little stubborn sometimes.”

How the Grinch Stole Christmas!

an argument breaks out between his parents and grandparents. Ann seems to mediate at first, then sides with Obama against her parents. “I listened to my mother tell her parents that nothing ever changed with them,” the younger Obama writes. Dispatched by his grandmother the next day to collect any dirty laundry from the apartment where his father is staying, he finds his father shirtless and his mother ironing. She appears to have been crying. He delivers his message and declines an invitation to stay. Back upstairs at his grandparents' apartment, Ann appears in his room. “You shouldn't be mad at your father, Bar,” she tells him. “He loves you very much. He's just a little stubborn sometimes.”

When he refuses to look up, she adds, “I know all this stuff is confusing for you. For me, too.”

Other books

Tied Together by Z. B. Heller

CRASH & BURN (Rule Breaker) by Arden, Susan

Under the Lights by Abbi Glines

Source Of The River by Lana Axe

Sinister Sentiments by K.C. Finn

Fallen Angel by Heather Terrell

How to Lose a Groom in 10 Days by Catherine Mann and Joanne Rock

War of the Princes 02: Dragoon by A. R. Ivanovich

Krapp's Last Tape and Other Dramatic Pieces by Samuel Beckett

BLUE MERCY by ILLONA HAUS