A Singular Woman (36 page)

The microfinance program was an extraordinary success. In June 1990, it was making 115,000 loans a month with a value of $50 million and an average loan size of $437. It was soon a major source of the bank's growth. During the East Asian monetary crisis of the late 1990s, when the repayment rate on the microloans remained higher than that of the small, medium, and corporate customers of the bank, the program helped the bank weather the crisis. As of 2009, the bank operated more than four thousand microbanking outlets in Indonesia. It had 4.9 million microloan customers and 19.5 million microsavings customers.

“If you work in the development racket, you're lucky at the end of ten years or twenty or thirty to be able to look back and say, âI think I did more good than harm,'” Richard Hook, who was hired as an adviser on the Bank Rakyat Indonesia project the same year as Ann, told me. “The non-successes are all too numerous. Often you inflict collateral damage, albeit unwittingly and unwillingly. This project met Indonesian needs. It was based in a massive Indonesian institutionâa state-owned commercial bank. It was run by Indonesians. We were external advisers. The concept was making small loans to low-income rural people. The conventional wisdom was you won't get repaid and these people don't know how to handle a loan, they were too innocent of sophisticated procedures and financial know-how to know how to handle credit. We didn't believe that. A number of Indonesians didn't, either. We worked together and made this project work. That was just such a delight.”

Patten was brilliant, creative, and not necessarily easy to get along with. Akhtar Hameed Khan, the microcredit pioneer whom he had known in East Pakistan in the 1960s, once described him as “the finest development worker I have ever met.” The son of a successful midwestern banker, he had grown up on a daily regimen of meat and potatoes so rigid, his daughter told me, that it drove him to swear off potatoes for life. He had spent most of his adult life in East Pakistan, Ghana, and Indonesiaâa long way from Norman, Oklahoma. A divorced father of three, he inhabited the persona of an inveterate bachelor. He liked people who did not need to talk all the time, and he hated the sort of questions that began with “Don't you think . . .” He was hardworking and occasionally napped on the office floor. For a time, he lived in a house with a two-story cage that served as home for a black Sumatran gibbonâuntil the gibbon terrorized various neighbors and found its way into the electrical wires above the street, necessitating a neighborhood-wide power shutoff. Patten was opinionated and blunt but not without compassion. After three months as office manager, Flora Sugondo went to him in tears, saying she wanted to quit because, working for Patten, she had become convinced she could do nothing right. Patten apologized, persuaded her to stay, and vowed never to treat her that way again. When Johnston, a graduate student in economics at Harvard, arrived in Jakarta for a temporary stint as a research assistant in Patten's office, Patten gave him a paper to edit, and Johnston “marked the hell out of it in red ink,” as he put it. Patten was thrilled. Johnston was suddenly the permanent project assistant. “When I got there, everybody was so happy,” Johnston told me. “I was one of the few people who could work productively with Dick.”

Ann was another. Patten valued Ann's ability to recognize what kind of research would be useful in building the microfinance program. They shared a certain midwestern straightforwardness and a fascination with Indonesian culture and Indonesian people. Patten operated the house in Menteng Dalam as a kind of guesthouse for expatriate consultants. During periods when Ann was between contracts or not renting a house of her own, she stayed there. She treated Patten like a favorite uncle, said Johnston, who lived in the house. Sometimes she called him her surrogate father. There might be as many as ten or twelve people at the table for dinnerâpot roast or meat loaf, and vanilla ice cream for dessert. Patten kept the lights dim and the radio tuned to the BBC. He liked Bachâ“up and down music,” as Ann dismissively called it. Patten found her good company and entertaining. Once, he told me, Maya telephoned Ann from Yogyakarta, where she was taking time off from college and working for a travel company, leading cultural tours in Java and Bali. An older, unmarried American tourist, who happened to be a teacher, had arranged to have a blind masseur come to her hotel. The woman had become hysterical, accused the masseur of molesting her, and had him arrested. Maya wanted her mother's advice. “First, give the teacher a good, hard slap,” Patten remembered Ann saying. “Then go to the police station and make sure nothing happened to the masseur.”

Recalling the story, Patten laughed.

“It's so entertaining and so indicative of the way she thought:

Just worry about the masseur.

”

Just worry about the masseur.

”

Ann's methodology in the field was meticulous. She designed novella-length questionnaires to be used as a guide for interviewing potential customers about matters ranging from working-capital turnover periods to the number of relatives employed without pay. For inexperienced research assistants, she appended handy tips. “Has the Respondent ever been inside a bank before?” one question asked. If not, why not? If the respondent answered that he or she was afraid of banks, the interviewer was to find out why. “This is an important question, so take whatever time is necessary to discuss it with the Respondent,” Ann wrote. Another question required that the interviewer fill out a chart with ten vertical columns under headings such as “type of account,” “maximum amount of savings,” and “use of withdrawals.” The interviewer was to list every savings account the respondent had had in the previous seven years, as well as other deposits through savings-and-loan societies, credit unions, and other organizations. “If the Respondent has any savings in kind, for example in a rice bank, list this also, but give a rupiah value underneath,” Ann's instructions said.

She had an unusual ability to adapt. With bankers, she came across as professional, methodical, and not the least bit eccentric. With older Indonesians, her accent and diction took on a precision that Don Johnston thought sounded faintly Dutch. Arriving in a village for the first time, she transformed herself into the beloved visiting dignitaryâher bearing regal, her silver jewelry flashing, her retinue in tow. “She was clearly the queen bee of the entourage,” recalled Johnston. “Then she gets there and they realize, âOh, this is not just a foreigner but this is a foreigner who can speak Bahasa Indonesia, and who knows a lot about what we're doing and who wants to talk to us about this stuff. And she has some connection to this big bank, BRI, but she's not a banker, so I don't need to be scared of her.'” She was even deft in her dispensing with inevitable Indonesian comments about her physical dimensions. When a boatman professed trepidation about whether the personage boarding his boat was going to sink it, Ann switched, humorously, to the role of the grand lady: How dare you! There was showmanship involved, but she was never inauthentic. “Ann was a genuinely complex person who had a really varied background,” Johnston said. “So she could legitimately tap those different experiences to build empathy with different people.” It made them want to line up and tell her their life stories.

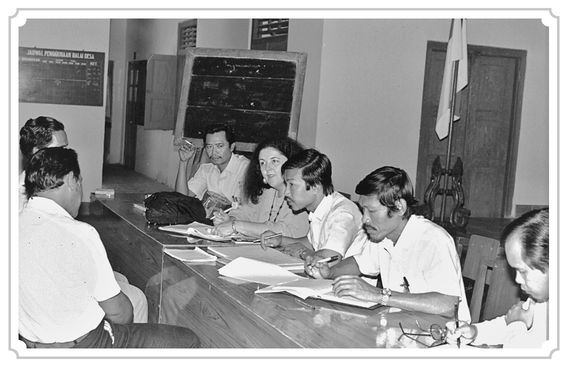

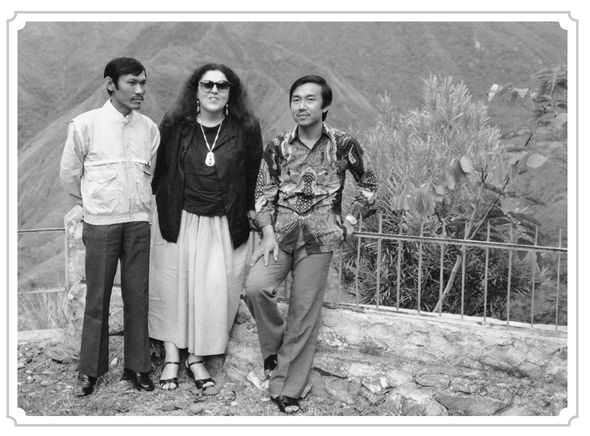

Interviewing bank customers, with colleagues, about 1989

On a field visit to village banks in the district of Sleman in 1988, Ann proposed a short detour to the village of Jitar, the home of a respected kris smith whom she knew. According to Ann's account, she was traveling with three carloads of bank colleagues and local government officials. At the smith's house, he invited the group inside for tea. Members of the group, laughing loudly and making raucous jokes minutes before, fell silent, sat formally, and then addressed the smith, Pak Djeno, with deep respect and deference. When Ann said she wanted to buy a small kris, the smith brought out four blades. “A deadly hush came over the room, and even whispering ceased,” Ann wrote later. For days afterward, her colleagues discussed the encounter. “The very fact that I had known a keris smith and had purchased a keris also caused a change in their behavior toward me. They began to show me some of the deference they had shown to Pak Djeno, speaking with greater respect and formality. Somehow, a little of his magical power had managed to rub off on me.”

Ann combined the discipline of a workaholic with a personal warmth that her Indonesian colleagues and subordinates described to me as maternal. She was not a practitioner of “rubber time”: If she had an appointment, she was never late. In the field, she might start work at nine a.m. and not wrap up until thirteen hours later. She would stay with an interview long after colleagues were ready to move on. She traveled with a Thermos and took her coffee black, no sugar. “Coffee is my blood,” she said; if she ever got sick, she said, she wanted intravenous coffee. She rarely seemed to get enough sleep. She tested survey questions on herself first, to feel what a respondent might feel. She would never risk insulting her host by declining food. When the manager of a bank branch in South Sulawesi threw her a surprise birthday party, including karaoke, she launched gamely into “You Are My Sunshine.” In the town of Garut, she turned her attention to a girl of no more than seventeen who was serving dinner to members of the team at their hotel. Ann asked her about her family, her marriage, her education. How much was she paid? Was it enough? Then, when dinner was over, she slipped the girl money.

On occasion, a misunderstanding across some cultural divide left Ann rattled. On a visit to a village in Sulawesi in 1988, an irate local official pursued Ann and her group, shouting furiously in a local language that none of them understood. He appeared to believe the group had failed to obtain his permission to enter the area. The confrontation subsided after some local residents intervened in the group's defense. But late that night, Ann remained upset and was unable to sleep. She asked a bank colleague, Tomy Sugianto, to accompany her on a walk around the outside of the hotel where they were staying. The hour was about one a.m., Sugianto told me. Ann, visibly exhausted, was on the verge of tears. She seemed haunted by the memory of the local official's fury and whatever misunderstanding had provoked it. She felt wrongly accused. “She only wanted to know why the man was so angry,” Sugianto remembered, “and what we did wrong.”

To her younger colleagues, she was Bu AnnâBu being an affectionate abbreviation of the honorific

Ibu,

a term of respect for mothers, older women, and women of higher status. She treated them, they felt, as family. If she went out to lunch in Jakarta, she would order an extra meal for her driver, Sabaruddin, and his family. She helped pay for his five-year-old daughter's surgery and for repairs to the roof and the doors on his house. In the town of Tasik Malaya, she pointed out to her team that the village chief, a successful businessman, had started out as a peddlerâevidence that anything was possible. To her young research assistants, she emphasized accuracy, rigor, patience, fairness, and not judging by appearances. “Don't conclude before you understand,” Retno Wijayanti recalled Ann saying. “After you understand, don't judge.”

Ibu,

a term of respect for mothers, older women, and women of higher status. She treated them, they felt, as family. If she went out to lunch in Jakarta, she would order an extra meal for her driver, Sabaruddin, and his family. She helped pay for his five-year-old daughter's surgery and for repairs to the roof and the doors on his house. In the town of Tasik Malaya, she pointed out to her team that the village chief, a successful businessman, had started out as a peddlerâevidence that anything was possible. To her young research assistants, she emphasized accuracy, rigor, patience, fairness, and not judging by appearances. “Don't conclude before you understand,” Retno Wijayanti recalled Ann saying. “After you understand, don't judge.”

She even tried her hand at matchmaking. In the fall of 1989, the bank hired a willowy twenty-four-year-old woman named Widayanti from Malang in East Java, who was soon assigned to help Ann and Don Johnston with a survey of potential microfinance customers. Ann quickly discovered that Widayanti was a Pentecostal Christian. Johnston, the son of a church musician in Little Rock, was a Southern Baptist. Widayanti began to notice that whenever she asked Ann a question about the survey, Ann would say, “Oh, just ask Don.” Did Widayanti know that Don had once been a Sunday school teacher? Ann asked her. To Johnston, Ann talked up Widayanti's intelligence, her command of English, her honesty and strong principles. To Flora Sugondo, the office manager, Ann confided that she wanted to match up Johnston and Widayanti.

Other books

The Genius of Jinn by Goldstein, Lori

Shadow Sister by Carole Wilkinson

Bali 9: The Untold Story by King, Madonna, Wockner, Cindy

Jasper Mountain by Kathy Steffen

A Drink Before the War by Dennis Lehane

Preschool Reading Success in Just 5 Minutes a Day by Louise Moore

The Confessions of Arsène Lupin by Maurice Leblanc

Untitled by Kgebetli Moele

The Scorpio Races by Maggie Stiefvater