A Step Away from Paradise: A Tibetan Lama's Extraordinary Journey to a Land of Immortality (44 page)

Authors: Thomas Shor

Yeshe.

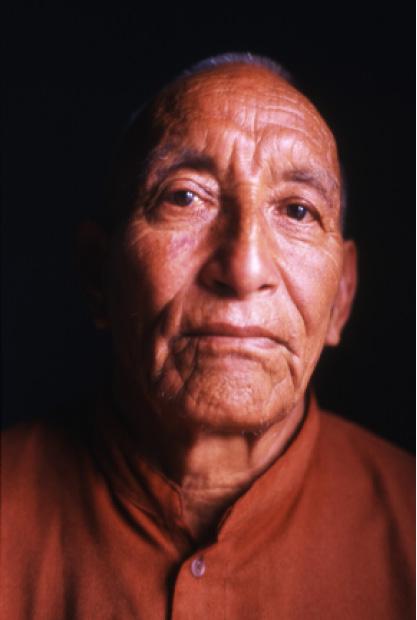

When I went to Simoling to investigate this story, I was greeted and instructed there by Lama Tashi. He was a large and powerfully built man who, at the age of eighty-one, exuded authority in everything he said and a strength of mind that matched his almost superhuman size. A close disciple of Tulshuk Lingpa and a learned lama in his own right, Lama Tashi was the

umzay

, or head of rituals, at the Simoling Monastery during Tulshuk Lingpa’s time. He holds the position to this day. I had met others who were close to Tulshuk Lingpa—others who had studied the ancient writings concerning Beyul. But they only scratched the surface of their experience when they spoke of such matters and were sworn to secrecy concerning the depths. None spoke with the weight, command and certainty of Lama Tashi. Tulshuk Lingpa had chosen him to break the path through the deep snow on that fateful day, and I understood why. His faith was as solid as an ancient tree, his learning well-founded. It was over forty years since that fateful day when he gashed open his head, broke his arm and three ribs in the white tide of snow. But his large-boned frame was still wrapped in a musculature like that of an athlete’s. His high cheekbones and prominent eyebrows made me feel as if I were in the presence of an American Indian elder.

Over the course of the two extended visits I made to the monastery in Simoling, Lama Tashi and I spent hours sitting in the monastery courtyard wrapped in jackets to keep out the frosty summer wind that swept off the surrounding peaks. Whenever we got too cold we’d move to the monastery kitchen and drink large cups of salted and buttered Tibetan tea. He not only answered my questions carefully but thought deeply about our discussions and raised issues and topics he thought would be important for my research. He spoke with the reasoned authority of a learned professor, one for whom the reality of Beyul was an unshakable truth.

Lama Tashi, the

umzay

of Shrimoling Gompa

Writing this book put me in the presence of many who had given up everything to go to Beyul: those for whom the tragic ending of the expedition caused not the slightest diminishment of their faith, for whom Beyul remains a reality greater than the world we inhabit. It was by being in their presence, more than any reading I did on the subject or discussions I had with people whose knowledge was from books, that I came to understand what it means to be on a quest for Beyul. Among all those I sought out in both the eastern and the western Himalayas, it was in Lama Tashi’s presence that Beyul was the most palpable, an unmistakable and unshakable reality.

Never did I feel closer to that crack than in his presence.

‘On that last day on the mountain,’ he told me, ‘the four of us had no doubt that we could make it. I think that is why Tulshuk Lingpa especially chose us to go with him. Not everyone had that belief, and that made conditions difficult. For twenty days we were practically at the gate, within sight of the pass to Beyul. Every day it would be sunny towards the pass when we left the cave but every day obstacles arose, storms of clouds, snow and wind.

‘Something wasn’t right.

‘If we were to make it, I began to think to myself, why such hindrances? Though I’ve not spoken of this, I can tell you that by day sixteen a tremendous conflict arose within me. Nobody understood better than I that one’s faith in one’s teacher must be total and that one must not contradict him, especially when he is preparing to open the way. My faith, both in him and in the reality of Beyul, was and is unshakable. I had been with Tulshuk Lingpa since he first arrived in Simoling and rid our village of the leprosy. This was long before he spoke of Beyul. He had made me the

umzay

, and left me in charge of his monastery when he left for Sikkim—a post I hold to this day since he never returned. He summoned me to Sikkim only when he felt the time was ripe for the opening. Yet after so many attempts and after each attempt failed when the weather turned bad and beat us back off the mountain and into our cave, the conviction began to arise in me that we should turn back, that we should return to Tseram or calamity would strike. Our rations were running out. Not everyone had the faith I had, which I knew was causing the disfavor of the guardian spirits and causing the obstacles to arise.

‘If one truly believed in the reality of Beyul, if one believed that Tulshuk Lingpa was the one chosen by Padmasambhava, if one

knew

that he had the key—then one would have no trouble turning back to await the right time and conditions. Pushing forward, it seemed to me, was a sign not of faith but of doubt. Since it was this lack of faith that was causing the obstructions, I felt I had to tell Tulshuk Lingpa that we should turn back. But I did not have the courage. Though I feared—and even foresaw—disaster, how could I contradict him? Wouldn’t this in itself be a sign of a lack of belief? Isn’t the ultimate test to follow the guru no matter what, even as conditions spiral out of control?

‘I was torn within myself those last days, unsure whether I lacked the courage to tell him my conviction or whether it was my faith that was lacking. While I was thus torn, the others were pushing Tulshuk Lingpa ever harder into going—especially after Wangyal returned from his excursion with Tulshuk Lingpa having seen the snow give way to fragrant greenery.

‘Did I correctly sense that Tulshuk Lingpa was himself wanting to turn back but was being swayed by his disciples? While I couldn’t muster the courage to speak to Tulshuk Lingpa, I tried to convince the others that we should turn back.

‘“Wangyal has seen it,” I said to them. “We can no longer doubt its existence. Since Tulshuk Lingpa is the one destined to open the beyul, as long as he is with us, we will always be able to go. The obstacles tell us that this is not the time. Therefore we should not push Tulshuk Lingpa, and we should turn around.”

‘The others were thinking differently. Since we had come so far and had left our homes and were willing to lay down our lives, they thought we should keep going at least to have a glimpse like Wangyal had.

‘“The need to see it can only come from doubt,” I pleaded with them. “Since Tulshuk Lingpa is with us and he is definitely the one destined to open Beyul Demoshong, we can go there any time. At any time it is accessible to us—so forget it. Don’t have this doubt of ‘Is it there, is it not there? Oh, I want to find out.’ Forget it. Our supplies are being depleted. We all know the dangers of melting springtime snow. If the time is not right to go now, the time will surely come. The key lies in Tulshuk Lingpa’s hands. Don’t doubt that for a second. When the time is right, there will be no obstacles.”

‘Nobody would listen. They could only reiterate: “Even if we don’t enter Beyul,” they said, “at least we want to see it from a distance like Wangyal did.”

‘It was like a wheel: once set in motion, it was very difficult to stop.

‘Tulshuk Lingpa heard us arguing that afternoon when he returned with Wangyal, and it was as if a cloud descended not only on the mountain. Tulshuk Lingpa’s face also became very dark.

‘The next day we tried again. That was the last day, the day Tulshuk Lingpa died.

‘If I had had enough courage to tell Tulshuk Lingpa, probably he wouldn’t have died. Perhaps we would have tried it later—secretly, with less people whose faith was great enough. Then we would have been successful.’

Lama Tashi looked away. His gaze rose over the snow-capped mountains on the other side of the valley from the courtyard where we were sitting, with our shawls flapping in the cold wind. He was silent for a few long moments. Then he turned to me and spoke.

‘Actually Beyul was a secret. No one should have known, just those who were prepared by their own inner work and by the teachings of Tulshuk Lingpa.

‘Faith in Beyul is not enough. It also depends upon your motivation for going there. The fact that Beyul is a place of unimaginable riches where everything will be provided can itself cause impurity. Even the purest of heart can be corrupted by riches. Those who are not prepared can easily find themselves going there for material reasons and not for the dharma. They say three quarters of the world’s wealth is in Beyul. So what we see here in this world is merely a quarter.’

I had heard this before. Géshipa had told me that Beyul Demoshong is so large you’d definitely need a chariot just to get around. Dorje Wangmo had told me that Padmasambhava had said half of the wealth of this world is hidden underneath Kanchenjunga. Kunsang had told me that Demoshong, which was the inner secret land within Sikkim, was three times larger than the outer Sikkim or Demojong, the Valley of Rice.

Don’t the pronouncements of the modern physicists echo a similar idea? Physicists can only account for a fraction of the matter that their theories and measurements tell them exists in the universe. They dub the rest ‘dark matter’ because they cannot see it, taste it, weigh it or in any way account for it. Though they know it exists, it cannot be measured as we measure things of this world. Even though they can only infer its existence, they know it exists—every bit as much as Tulshuk Lingpa’s disciples know of Beyul’s existence. As with Beyul, no one’s ever seen it. No one has ‘been there’. The physicists go even further than the seekers of Beyul. They say the visible world of electrons, protons, neutrons, quarks and all the subatomic particles, electromagnetic forces and everything existing in the three dimensions including you and I, all the matter subject to gravitational force—what Kunsang would call the ‘outer’ Sikkim—makes up only

2 per cent

of the universe.

Lama Tashi was adamant about why Beyul exists, and what Padmasambhava’s purpose was in hiding it.

‘Beyul isn’t a place to simply sit back and enjoy oneself because all one’s needs are taken care of,’ he told me. ‘It isn’t as if upon entering Beyul you suddenly become a millionaire and live a life of worldly pleasures. Padmasambhava hid Beyul in the eighth century as a place free of care so those who enter could have uninterrupted practice. Practice has one goal: to develop compassion for others. Here we don’t have time to practice. It is extremely difficult to develop compassion. The entire world conspires for the strengthening of the ego and its drive to put itself first. How rare it is for someone to be developed to the point of putting

others

first!

‘Now times are difficult. Everywhere we look we see war. Everything brings distraction and destruction. Padmasambhava foresaw these dark times. The search for Beyul is only important at the end of time, when the world is coming to an end. It is for that we have the lineage of the

lingpas

, those destined to find the

ter

concerning Beyul.

‘Now it is difficult even for those with a pure heart to help others. We are conquering the material world but we are destroying it as well. Soon we will have nowhere to run. They are building an eleven-kilometer tunnel through the mountains that will connect Lahaul directly to the lush Kullu Valley. Twelve months a year you’ll be able to drive to Simoling. The opening of the tunnel will be right there, on the other side of the valley. We’ll be able to come and go at will. Since people first came to this valley, we’ve been snowed in half the year. Now they will “improve” our situation. But what will it bring us? Maybe a lot of tourists.

‘You cannot make this world a Shangri-La. No improvement will ever get you there. To reach that state of happiness, you must let go of this world. 100 percent. Maybe it will soon be time again to attempt an opening. It is written in the ancient books that when the dharma is becoming lost, when there is nowhere else to run, the Great Door of the Secret Place will open. Times are getting rough.