A Step Away from Paradise: A Tibetan Lama's Extraordinary Journey to a Land of Immortality (40 page)

Authors: Thomas Shor

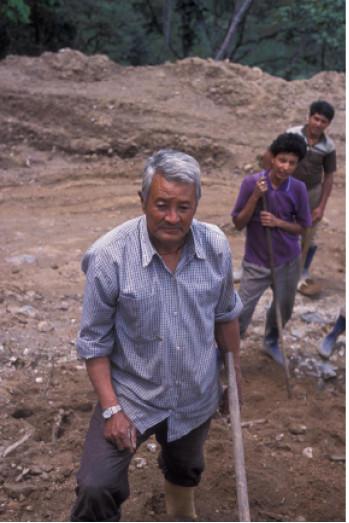

Atang Lama, age 74, Tashiding, 2005

Baichung Babu was another Sikkimese who went with Tulshuk Lingpa. He was in his late twenties at the time; so he was in his early seventies when I met him. His name often came up when I spoke with the Sikkimese followers of Tulshuk Lingpa. It was not easy to find him, though I did track him down following trails and paths through villages in West Sikkim. When I located his house, I was informed that I’d find him somewhere up the steep slope working on the road. I climbed a trail until I came upon a gravel road under construction. I followed it until I came upon a small gang of boys working on the road with a white-haired man pounding a huge boulder in the roadbed with a maul, trying to crack it. The man was Baichung Babu, and he was the foreman.

It was a brilliant, clear day. Mount Kanchenjunga was glistening to the north not so far away, with its white slopes sharp as a jagged razor piercing the deep blue sky and a plume of snow streaming from its very peak. Baichung Babu was powerfully built, especially for an elderly grey-haired man. He was putting his entire body into cracking the huge boulder. As I approached, I wondered what it had been like for him to return to his daily life and to live the intervening forty-plus years within sight of the mountain into which he had expected to disappear.

If only that crack had opened forty years earlier and he had entered a land free from toil, he wouldn’t be putting his effort into cracking this boulder. I wondered whether this realization had turned him bitter with the years. So I approached him, and he let the head of the maul come to rest by his feet.

I told him my business, that I was interested in his feelings about his trip to Beyul when he was a young man. The boys gathered round, and he spoke rapidly—for them as much as for me—as he told the story of going with the lama up the mountain in order to find a place where you’d never have to lift a shovel or pound a maul. To the boys, such a trip made immediate and intuitive sense. Had a lama appeared at that moment who knew the way, I’m sure they would have left their shovels on the side of the road and followed him. Baichung Babu’s faith had not diminished with time. He didn’t seem embittered that here he was, white-haired and over seventy years old, still pounding rocks to earn his daily fare. His only regret was that the lama died at the crucial moment. ‘I won’t get the chance again,’ he said. ‘Such a chance only comes once in a lifetime. Now I’ll have to wait till another.’

Baichung Babu and his road crew.

I asked Rigzin Dokhampa why he thought Tulshuk Lingpa failed.

‘Tulshuk Lingpa was the right person to go,’ he said. ‘But there were many other people involved. Too many. Not all of them had the right karma. Without practice and accumulating merit, you cannot go. You have to be clean. If those who go with the right lama have good karma, they can certainly make it. Even then, it depends on time. Timing is everything.’

‘How can it be one’s destiny,’ I asked, ‘to open a beyul and fail? Both Tulshuk Lingpa and Dorje Dechen Lingpa were

tertons

, both found terma and both knew from within the way to Beyul Demoshong. It appears they were even attempting the same gate on the same snowy slope. How can you fail your destiny?’

Rigzin sat silently collecting his thoughts before speaking. ‘Seeds—like wheat or corn—have the power within them to grow. But what is within the seed is not enough. Doesn’t every seed need the proper soil and the right amount of water and sun? As it is for the seed, so it is for the terton. To discover terma, the terton must have the proper conditions. Both of these lamas had the karma to find the Hidden Land but nothing stands in isolation. Buddhism teaches the interdependence of all things. For the seed within any of us to grow, it needs proper conditions. Seeds need water.

Tertons

need not only a female consort, or

khandro

, to open a beyul. They also need disciples with unflinching faith.’

‘Were Dorje Dechen Lingpa and Tulshuk Lingpa the only

tertons

who have attempted to open the Hidden Valley?’ I asked.

‘Many

tertons

have tried, over the years.’

‘Were they the last two?’

‘Yes, as far as I know.’

‘What would you say to the typical Westerner,’ I asked, ‘who would argue that there are no hidden lands to be found, that by now satellites have photographed and mapped every inch of the earth?’

‘So far,’ Rigzin said, ‘even great scientists can only see germs with microscopes and other modern-day machines. With only their eyes, these microbes would have remained invisible and they would never have discovered them. Beyul is much the same. For the practitioner of Buddhism the instrument is consciousness itself. We develop our consciousness so we can see what does not appear to the common eye. That is the lens that allows us to see what remains hidden to your airplanes and satellites. Besides, Beyul is protected by a “circle of winds” that would prevent an airplane from even flying over it. There are many things that cannot be seen by scientists. No machine will show you Beyul. None will take you there. Anyone can look into a microscope and see the microbe. Only those who have developed their consciousness have a chance of entering Beyul. Developing such a level of consciousness, we Buddhists believe, takes many lifetimes. It is extremely rare. If everybody could go there, why would it be called the Hidden Land? It would be called the Open Land. Wouldn’t it? Those who have the karma to go there can go in this life.’

‘You were lucky to be born in Tashiding,’ I said. ‘I was born outside Boston.’

‘You were born in the richest country,’ Rigzin said. ‘Here in India, and in Sikkim, we are the poorest country but the holiest.’

‘Which would you choose?’

‘For the next life,’ he said, ‘our world is better. For this life, your world is better.’

‘Having been in both countries,’ I said, ‘what I see is that people are happier here.’

‘Really?’ Rigzin said. ‘That is the blessing of Padmasambhava.’

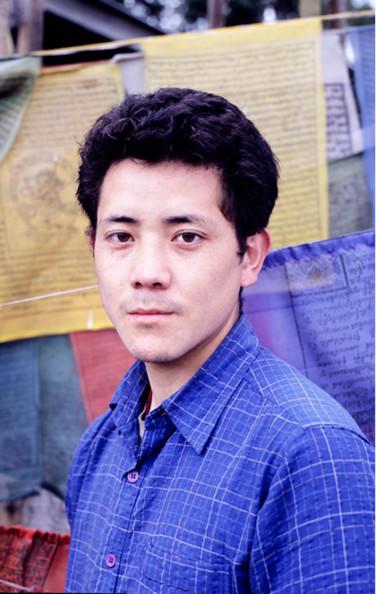

Wangchuk.

Wangchuk and I spent a lot of time together while tracking down his grandfather’s story, and we grew quite close in the process. We travelled together to Sikkim twice, and over the course of two or three years we spent a lot of time crammed together in the backs of jeeps bumping down rough roads clinging to mountainsides in the quest for ‘grandpa’s’ disciples.

When meeting Tulshuk Lingpa’s disciples, Wangchuk’s presence gave me an immediate stamp of legitimacy that opened people to telling their tales. It was often a deeply emotional experience for those who had courageously followed Tulshuk Lingpa to the Gates of Paradise to find on their doorstep the grandson of their beloved lama and a foreigner wanting to hear what they had to say. As the gates opened to memories of what was for many their greatest adventure and their closest brush with something transcendent to their own selves, the specter of the beyul appeared before them. They described the reality not of how it felt to be on the threshold of another world but how it

feels

. Such was the immediacy they still felt after over four decades. I was always grateful to repay Wangchuk’s gift of accompanying me and opening doors by his presence and translating for me by having him present to receive the stories. He had grown up knowing his grandfather was a lama and had died in an avalanche but as is often the case, he had scant idea of his ancestor’s story or the extraordinary way his father had grown up.

The last of Tulshuk Lingpa’s disciples that Wangchuk and I spoke with was a woman named Passang Dolma. We had long been through with our interviews when Wangchuk told me that a friend of his, to whom he had been telling his grandfather’s tale, had told him he had once heard Passang—his mother’s friend—say she had been a disciple of Tulshuk Lingpa. Since she lived in Darjeeling, it wasn’t difficult to visit her. Passang must have been in her early or mid-sixties, which would have made her a very young woman when Tulshuk Lingpa was in Sikkim. She was neither learned nor particularly religious. She seemed in all respects a normal woman who had happened to participate in these extraordinary events.