A Step Away from Paradise: A Tibetan Lama's Extraordinary Journey to a Land of Immortality (36 page)

Authors: Thomas Shor

Garpa told me that once the Dalai Lama came to Tashiding. He, too, was surprised to hear that all those

mani

stones were carved by one man, and asked to see the man who had carved them. Garpa was brought before the Dalai Lama and the Dalai Lama looked mirthfully into Garpa’s eyes and pulled his beard. He held Garpa’s face between his two hands and laughed. He told him to continue his good works, which Garpa intends to do, though he confided in me that in the end he intends to go to Bodh Gaya—the place of Buddhist pilgrimage where the Buddha reached enlightenment. ‘If I go to Bodh Gaya,’ Garpa said, picking up his chisel, ‘I don’t think I’ll come back. I will go there and meditate.’

When I asked Garpa about his time with Tulshuk Lingpa, he laughed.

‘My name is Garpa,’ he said. ‘In Tibetan, that rhymes with

trapa

, which means messenger. Tulshuk Lingpa gave some of his disciples new names like Géshipa, which is a crazy name meaning Four Hundred. Who ever heard of someone named Four Hundred? Because of my name, he gave me the title of the Messenger of the Hidden Land. I was young and strong. While Tulshuk Lingpa was living in Tashiding and he went to Yoksum or some other place, he’d always use me as his postman to relay messages. I became a tremendous runner. I could run all the way from Yoksum to Tashiding in a few hours. You wouldn’t know it now from looking at me but I developed great endurance.

‘When Tulshuk Lingpa fled Sikkim and went to Nepal—to Yamphodin and Tseram—he still had me act as messenger to relay messages to those left behind in Tashiding but now I had to cross a 16,000-foot pass. In total I made the return journey six times, plowing through snow up to my waist.’

It is impossible to say how long they stayed in Tseram. In fact details of times and dates were all incredibly difficult to pin down, and some proved impossible until the end. As far as I can guess, they were in Tseram a few months when one day Tulshuk Lingpa took out his

melong

, the convex brass mirror used in the

trata melong

, the mirror divination. He stuck the mirror into a plate of rice and performed a puja that put Yeshe into a trance.

Yeshe was nineteen at the time. Her older sister was the

khandro

, and had gone down to Yoksum in order to deliver a child by Tulshuk Lingpa some months before, a girl by the name of Pema Choekyi. Somewhere along the line, Yeshe also became his

khandro

.

When it came to the subject of Tulshuk Lingpa and his

khandros

it was difficult to get people to talk. Since it was almost as indiscreet for me to ask about his lovers as it was for those who knew to speak about them, I dared ask but only got knowing smiles and evasive suggestions in response. A few ventured as far as saying with an enigmatic smile that he

was

charismatic and extremely handsome. It is easy to imagine that someone who could inspire hundreds of people to forsake their worldly goods and the very world itself might very well have power over women. In the non-answers I received it became clear that Tulshuk Lingpa was both attractive to women and had his experiences with them, though you can be sure that as with everything else in his life, his experiences with women weren’t of the common variety. He was a great mystic, and the women in his life played a role something similar to that of Beatrice who guided Dante through Paradise in the

Divine Comedy

.

I spent quite a bit of time with Yeshe, and she herself told me what many others had—that she was also his

khandro

, though she had been married three years earlier at the age of sixteen. I suspect the fact that she was his khandro meant she and Tulshuk Lingpa were lovers, though I am not sure. Tantric secrets might be easier to unravel. What she couldn’t hide was her deep and abiding love for him. After over forty years, she still saw him in her dreams. She’d see him performing a puja and blessing her.

Yeshe described to me that day in Tseram when Tulshuk Lingpa performed the

trata melong

, the mirror divination, and had her look into the mirror. She saw three beings reflected in the mirror, and they were hovering off the ground. One was completely white, and two were completely red. They were slowly floating towards her.

Tulshuk Lingpa said the white one was the sadag, the spirit owners of the land, and the two red ones were the

shipdak

, the guardian deities of the land. That they were floating towards her meant that they were coming from Beyul to greet them. This was an extremely good omen, for without the cooperation of the local deities and the spirits who guarded Beyul it would be impossible to get anywhere near the gate. The beyul were Padmasambhava’s most well-guarded secrets, which would be given up only when circumstances necessitated their opening and only to those pure of heart, intention and motivation. Without the cooperation of the deities and without the necessary purity of heart, clouds would descend, snow would fall and winds would rise up and blow you off the mountain. Support of the deities was never simply given, no matter how predisposed they were to you. They had to be constantly appeased and won over by performing numerous pujas.

When Yeshe saw the deities greeting them, Tulshuk Lingpa decided it was finally time to move higher in order to open the Western Gate to Beyul Demoshong.

‘The time has come. The time has come. The time has come,’ he said.

He chose twenty of his closest disciples to make the opening. They were chosen for their purity of heart, the depth of their practice and the sincerity with which they had given up all ties with the world.

As they were preparing to leave, those who were to stay in Tseram awaiting word that the gate had been opened gave lavish advice to those travelling with Tulshuk Lingpa.

‘Just remember that nothing is impossible,’ they counseled. ‘As you go to open the Gate, the spirits will feel that you are intruding. They will call forth storms and bring down rain, hail and snow. At that time you must keep your minds pure and don’t allow yourselves to be infected by doubt. No matter what Tulshuk Lingpa says don’t contradict him. Even if he says, “Bring me the moon,” don’t tell him it is impossible. Try. Keep your minds pure.’

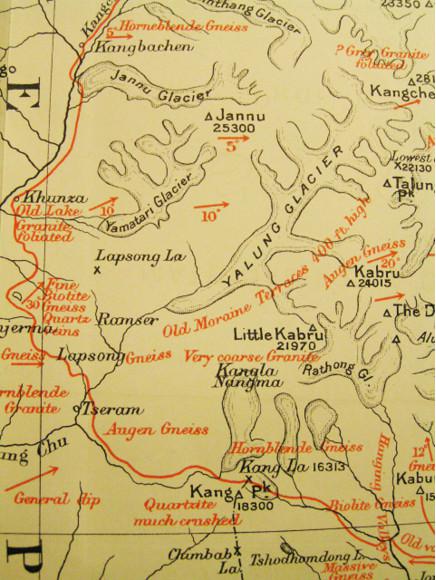

Map 3. Southwest slopes of Mount Kanchenjunga

from

Round Kanchangjunga

by

Douglas W. Freshfield, 1903

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY

Opening the Gate

‘Somewhere over the rainbow

Skies are blue

And the dreams that you dare to dream

Really do come true’

—Yip Harburg

So it was, amid tremendous excitement, that Tulshuk Lingpa and twenty of his closest disciples ascended the steep slopes above Tseram in order to find and open the Western Gate to Beyul Demoshong. They took with them bedding, food and

pechas

. Of the twenty, all were men except for three young women—the

khandro

, her sister Yeshe and another woman who has since died. The

khandro

had strapped to her back her and Tulshuk Lingpa’s eight-month-old daughter Pema Choekyi. This was in the early spring of 1963. Of the twenty, many have died in the intervening decades. Others—like Mipham, who has been in deep retreat for years in a cave in Bhutan—could not be traced. I was able to speak with eight of those who went above Tseram and piece together what happened.

Years before, Tulshuk Lingpa had been given directions to Beyul by Khandro Yeshe Tsogyal in a vision; so he knew the way. Yet the directions he was given, which he wrote down in his

neyik

or guidebook—titled

The Great Secret Talk of the Dakinis Showing the Way to Demoshong

—demonstrates that the landscape in which the gate was to be found was not purely physical. While it describes the way to a particular place, the landmarks are clearly visionary as well as cryptic. This terma is after all a treasure map to a hidden paradise full of unimaginable treasures, both physical and spiritual. It reveals secrets while concealing them.

I was given a copy of this guidebook by the lamas of Tashiding only because I was with Wangchuk, Tulshuk Lingpa’s grandson. I could have it only after I made the solemn promise that I would not let others see it, publish it in its entirety or publish excerpts that would in any way divulge its secrets. This I have done in the following excerpts:

Within the fort of the snow mountain there are four treasures packed with tremendous wealth that will fulfill your wishes. There is a pond of nectar, and within that pond are eight

nagas

[serpent gods] protecting a treasure of unimaginable jewels. There is an unthinkable paradise of the owner of the hidden treasures, as well as a paradise of the protector in charge of the whole world. There are countless natural formations, great hidden treasures of dharma and wealth and some small hidden treasures as well.

At the foot of the snow mountain like a lion, which is full of rocks encircled by rainbows, there is a treasure of innumerable jewels. Within the rock mountain in C there is a treasure of wish-fulfilling gems. In the long cave called L there is another treasure of wish-fulfilling gems. In the East, below Kanchenjunga, are treasures of the three different salts. In the mountain called L there are treasures of life and religion. In the central mountain called T there is a great treasure of immortality. In the northwest, in a great cave at Y, there is a copper horse that will conquer all three worlds. And there is a dagger there that will conquer all illusions. In the holy place of the auspicious

dakini

there is a granary of corn.

After describing a dizzying and kaleidoscopic array of treasures and secret places, ‘paradises of

nagas

and gods and

dakas

and

dakinis

’, which are to be found ‘on the mountain, in the valley, on the rocks, in trees, as well as in the springs’, it says, ‘These are the secret places of Padmasambhava, linked like a net.’ Lest you think great secrets have been revealed, it then goes on to say, enigmatically, ‘These are the well-known secret places.’