A Step Away from Paradise: A Tibetan Lama's Extraordinary Journey to a Land of Immortality (33 page)

Authors: Thomas Shor

The small grassy field below the monastery was teeming and into it walked Tulshuk Lingpa, followed by his daughter Kamala holding a huge tray of sweets. Just as they were coming down into the field, Kamala stumbled on a root and the tray of sweets scattered.

‘The omen is very important for us,’ Rigzin told me, ‘wherever we go, whatever we do, we have to see the omen. That was a very bad omen, coming right when it did, when her father was about to perform a miracle. If Kamala hadn’t dropped that tray Tulshuk Lingpa would have been able to take out

ter

that day, and there would have been a seven-year period of peace. But she dropped it so he couldn’t, and that seven-year period didn’t occur.’

Moments after Kamala stumbled and scattered the tray Tulshuk Lingpa grabbed on to the shoulder of a lama on his right, and it took two lamas just to hold him up for he suddenly became deathly ill. Hardly able to breathe, he broke out into a cold sweat and his head was spinning. It could have been a heart attack.

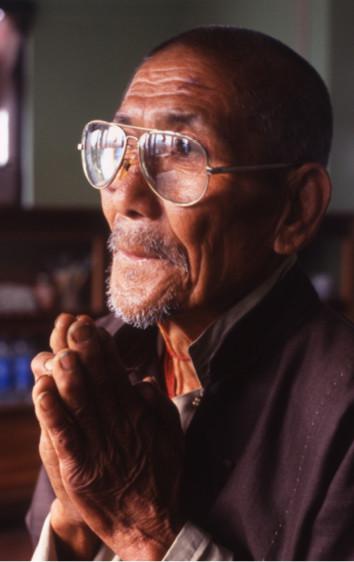

This sudden turn of events needed an equally spontaneous response to turn it around. This is where Atse came in. Atse, whose real name is Sonam Kunga, was one of the lamas of Tashiding. He had a peculiar reputation that was easily summed up in a single word: Cracked. For the unique logic that made him who he was had tremendous gaps in it, and it was easy to imagine his shaved head cracked right down the middle. He was fond of barley beer and by midday was usually incoherent. As a lama Atse was a disaster.

In a rare moment of lucidity some years earlier, Atse had memorized the text of the

Shabden Soldep

, the ritual one chants when a high lama becomes ill.

It was eight in the morning.

Atse wasn’t yet drunk.

He had been walking around with this text in his head for years.

This was his moment.

Atse

Atse stepped out of the crowd, stood next to where they had laid Tulshuk Lingpa on the ground, and in a voice at once sonorous and sure of itself he began chanting to bring Tulshuk Lingpa back from the brink of whatever abyss he was falling into. So much concentrated feeling was in his voice, such inner authority, that silence fell on the crowd. It was a solemn moment, with only the sound of his voice and the wind rustling the high grass. By the time he was through, everyone was concentrating so intently on Atse that they didn’t notice Tulshuk Lingpa had gotten back on his feet, his recovery having been as sudden and unexpected as the onset of his mysterious illness.

Over forty years later this chant was still swimming around in Atse’s brain. When I visited Tashiding with Tulshuk Lingpa’s grandson Wangchuk, we were awakened at six one morning by a loud rapping at our door. It was Garpa, another former disciple of Tulshuk Lingpa, holding Atse firmly by the shirt collar. He shoved Atse into the room, told me to get my tape recorder and then commanded Atse to sing. Though Wangchuk and I were both still half asleep, there was Atse standing in the center of our room, chanting in a deep voice as only a lama can, the entire text of the

Shabden Soldep

ritual. We had seen Atse the previous days, and he was always so drunk he could hardly stand. Garpa had picked this moment because it was the only time of the day Atse was reasonably sober. The moment Atse had completed the chant, Garpa grabbed him again by the shirt collar and led him out of the room before he could open his mouth again and put his foot in it.

At the moment Atse had finished his chanting all those years ago on the grassy field below the Sinon Gompa, Gonde Drungyig—the official of the Ecclesiastical Department who had first informed Tulshuk Lingpa that he had to perform a miracle—arrived on the scene.

The miracle could begin.

Tulshuk Lingpa led the representative, his main sponsors, closest disciples and family down a short path to where large smooth stone shelves jutted out over the empty space of the valley. There wasn’t enough room for everyone there so people crowded the slope above, back to the small field where they’d started. The lamas started burning clouds of

sang

.

‘From today onwards,’ Tulshuk Lingpa said, ‘there is no one, not even a king, who can either stop us or help us. We can appeal only to the

dharmapala

and

mahapala

, the guardian spirits of Beyul and the keepers of the gate. From today it starts.’

He took out the

pecha

he had received as

ter

above Dzongri, the text he’d received from the

dakinis

especially to appease the guardian spirits of Beyul and to entice them to open the way. He unwrapped it and held it in his hands. As he began chanting the text, Mipham, Namdrol, Géshipa and the other senior lamas looked at each other. They understood the significance of his reading this text. Each, in his own way, was ready for a tear in the fabric of reality.

Since no one knew what form the renting of reality would take and what miracle was about to occur, some were looking intently at Tulshuk Lingpa. Others were watching the sky, awaiting a sign. Yet others were looking towards Mount Kanchenjunga, because that is where they were to find the secret hidden country. One man told me he was looking down the steep slope to the Tashiding Monastery because it was the holiest place.

When Tulshuk Lingpa finished the text, he was standing in a dramatic pose with his right foot in front of the left. When he lifted his forward foot, there—where no one was expecting the miracle to occur—imbedded in the stone, was the imprint of his foot.

Tulshuk Lingpa’s Footprint,

Sinon Gompa, West Sikkim

Rigzin recalled for me that he was there and personally saw the rock flowing like water. ‘The rock was boiling and red in color,’ he told me. ‘My brother saw it also; everybody who was there saw this.’ Others described to me smoke rising from the rock, and the collective gasp that went through the crowd at the sight of their lama leaving his footprint in stone.

There is a strong tradition within Tibetan Buddhism, especially in the oldest branch, the Nyingma, of great lamas proving their miraculous powers by leaving their footprints in stone. Padmasambhava’s preserved footprints are found wherever tradition says he visited and they are still, after twelve centuries, places of pilgrimage. The great lamas of the past have even left imprints in stone of their hands, elbows and heads. Yet leaving an imprint in stone was a deed of the legendary heroes of the past, and none could recall a lama having performed this deed in anyone’s living memory. As an old lady told me, even the Dalai Lama—the spiritual and temporal leader of the Tibetan people—had never performed such a miracle.

Tibetan Buddhism is not the only faith that has a tradition of their holy men leaving footprints in rock. There are two alone on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. One is in the Al-Aqsa Mosque, Islam’s third-most holy site. It is believed by the faithful to be that of Mohamed. The other, in the Christian Chapel of the Ascension, is purportedly that of Jesus’ right foot and was left just before he left this world forever and ascended to Heaven. The Christians believe the Al-Aqsa Mosque footprint was left not by Mohamed but by Jesus. They believe the Muslims broke the rock where Jesus ascended to heaven and that it is actually Jesus’ matching left footprint, a controversy we certainly won’t enter into here.

As word of the miracle spread up the hill to the small field and the monastery a light rain began to fall, a special and auspicious type of rain with widely spaced individual drops—large and filled with sunlight—known in Tibetan as a Rain of Flowers.

The crowd parted to allow Tulshuk Lingpa and his lamas to climb back up to the monastery through clouds of incense, the very air resounding with the sound of horns and conch shells. With pressed palms, they bowed and prostrated themselves before this miracle-working lama. Then the hundreds who had gathered in Sinon that day filed by the footprint and paid homage to it.

I have spoken with many people who were present that day for Tulshuk Lingpa’s miracle. While some say the rock began to seethe and bubble and a purple smoke arose, others simply say they were just looking at the sky and suddenly it was there. Most agree the footprint deepened with time, and moisture came out of it. People bent down to put their forehead to it and many tried to take up the moisture with a corner of their clothing. Some wanted to lick the footprint but they were stopped by others who thought that would defile it.

About two hours later Tulshuk Lingpa was with his family inside his wood-slat hut at the monastery having a bite to eat after the morning’s exertion when there was a loud and aggressive knock at the door. Kunsang opened it to the highest law official of the kingdom: the police commissioner who, with pistol holstered and ready, was backed by ten uniformed policemen with rifles. They burst into the room and started ransacking their things.

‘Where is this miracle you have been promising the king?’ the police commissioner demanded. ‘I must see you perform it.’

Yab Maila pushed through the armed police guarding the door. ‘You have missed the miracle; it’s already occurred,’ he averred. ‘It was announced for 8 a.m. It is now after 10. Where were you?’

‘I was galloping my horse up the hill from Legship. We are far from the capital and it took longer than I thought. If you are to do a miracle for the king, you must at least wait until the official representative of the king arrives!’

‘We waited,’ Yab Maila said, ‘and he came. We didn’t start until Gonde Drungyig arrived. You, sir, I’ve never met.’

‘Gonde Drungyig wasn’t deputed by the king to view the miracle. I was.’

Just then Gonde Drungyig pushed into the room.

‘It is true,’ he said. ‘Last time I was sent by the king. But today I came as a private citizen, out of my own interest.’

The police commissioner cleared the things from a low table on to the floor with a sweep of his arm. Out of his jacket he produced a large map of the Kingdom of Sikkim, which he unfolded and laid on the table.

‘If you have it in mind to take His Majesty’s subjects to the hidden valley of Shangri-La, I demand you show me on the map exactly where on the slopes of Mount Kanchenjunga this hidden valley is. In the name of the king I demand that you show me!’

‘If Beyul were on the map, it wouldn’t be Beyul,’ Tulshuk Lingpa calmly said. ‘You won’t find it on any map. Beyul exists, but off the map.’

This infuriated the police commissioner.

‘What do you mean you won’t find it on a map?’ he insisted. ‘Is it too small to put on the map?’

‘No,’ Tulshuk Lingpa said, calmly. ‘Rather it is too large. Your map of Sikkim couldn’t contain it, for the Great Hidden Valley in Sikkim is three times as large as the outer Kingdom of Sikkim. Besides, if it were on the map, everyone would go. What would be the use? No one would need a terton to open it.’

The police commissioner was practically fuming.

‘You say you performed a miracle? Show it to me.’

Tulshuk Lingpa led the police commissioner with his ten-strong escort armed with rifles down to the stone outcropping of rock to see the footprint. The police commissioner bent down and examined the footprint as if it were a crime scene. He scratched it with his fingernail. ‘You have made this by hand. You have carved it,’ he declared. ‘Besides, since I wasn’t here when this occurred, how do I know the footprint wasn’t already here when you put your foot on it? Bring me some of the old people of this village. I demand to know if this footprint was here before.’