A Step Away from Paradise: A Tibetan Lama's Extraordinary Journey to a Land of Immortality (35 page)

Authors: Thomas Shor

‘We’ve heard you are going to Heaven with your lama.’

‘That’s not true; we are only going to Tseram. We have a six-month puja to perform. We must do it every twelve years.’

‘Are you sure you’re not going to Heaven?’

‘Entirely sure: 100 per cent.’

‘I can issue you permits to go to Tseram but only if you promise you’re not planning on going to Heaven. Because if I give you permits to go to Tseram, and if I later hear you’ve gone to Heaven, it’s my head on the block. The king will come here personally and chop it off! I’ll lose my head, and everyone else around here will lose their jobs. I can grant you permits but you must promise!’

‘We promise: we have no plans whatsoever of going to Heaven.’

This was a story Kunsang was particularly fond of repeating at odd moments, when we were speaking of other things. ‘It was damn crazy,’ he’d suddenly blurt out. ‘That time in Taplejung, the army man saying, “If you go to the Hidden Valley, king coming—cut my head!” We said, “No, no no. Only puja. Every twelve years we go to Tseram, doing puja, coming back.” “OK, then. I give you permit. But if you go to the Hidden Valley—cut my head. Cut my head!”’ Kunsang would tell this story laughing hysterically and swiping his hand across his neck.

The five representatives with Jinda Wangchuk at their head returned to the camp at Yamphodin with a six-month permit for everyone to go to Tseram. They had even extracted a promise that if after six months they hadn’t “gone to Heaven”, they’d be granted an extension.

Kunsang told me that once the army left them alone they stayed in Yamphodin just long enough to gather supplies. As seemed to be the pattern, his disciples—especially his oldest ones from Himachal Pradesh—were pushing him to go higher immediately and open the gate. It was a long time since they had left their homes. They had crossed India to Sikkim and now to Nepal in order to go with him to Beyul. Their money and supplies were running out. They were growing impatient. Once-proud sponsors were beginning to wonder where their next meal would come from. Word of their whereabouts had reached Sikkim, along with the rumor that he’d be opening the gate at any time. Nobody wanted to be left behind. There was a constant flood of people over the mountains from Sikkim to Yamphodin swelling their numbers, constantly drawing increased attention to them.

Once the authorities found out they had been hoodwinked and that Tulshuk Lingpa

was

taking them to Heaven, the army was sure to reopen the investigation and revoke their permit. Fearing once again that he’d end up in jail and not in Beyul, Tulshuk Lingpa announced that they’d be shifting to Tseram, an isolated place where no one would bother them. Even the nomads, who grazed their animals on the higher slopes of Mount Kanchenjunga and used Tseram as a camp, wouldn’t be there since it was winter.

Tseram, a one-day trek from Yamphodin almost straight uphill, was not far from the glaciers that cap Mount Kanchenjunga. Tulshuk Lingpa, his family and main sponsors occupied the abandoned wood-slat huts in the settlement, while the others lived in makeshift tents and in the caves that dotted the landscape.

In an attempt to keep their numbers from swelling unmanageably, Tulshuk Lingpa sent regular messengers sneaking over the Sikkim border—which was just up a steep rocky slope from Tseram—to tell the people who were still arriving at Tashiding in order to find him to stay there. He conveyed that he’d inform them when the time arrived to open the gate. Those who knew his tulshuk nature and that he could decide to open the way on the spur of the moment continued to climb over the high mountains to Tseram so as not to be left behind. This increased the pressure on him to open the way. Food had to be brought from Yamphodin, and with time even the market at Yamphodin wasn’t large enough to supply their needs. They had to go further to Taplejung, which of course was dangerous since the army headquarters was there.Kunsang described the time in Tseram as a very happy time. ‘We would go to the jungle where there were many birds,’ he told me. ‘I used to talk with the birds. I would whistle and the birds would sing back. Once some people heard me whistling to a bird and asked me what I was doing. “I’m talking with the guardian deities,” I told them, and they laughed. We used to talk with our echoes too. Everybody was happy. The birds were happy; we were happy. There were mountain goats with curved horns around Tseram.’

When some people from Yoksum were returning there, Tulshuk Lingpa sent Kunsang with them. He was to personally deliver his father’s promise that he would let them know when he was going to open the gate to Beyul. The idea was to convince those in Sikkim to stay there and not further strain the already strained conditions in Tseram. Kunsang was also to come back with supplies.

It was a three-day trek from Tseram up over the pass into Sikkim and down through Dzongri to Yoksum. Since Tulshuk Lingpa had fled Sikkim for Darjeeling under a cloud of suspicion, the arrival in Yoksum of the lama’s son Kunsang had to be top secret. As Kunsang told me, ‘I was also a bit crazy at that time. If they had caught me, they would have thrown me in jail.’ The king had his spies.

When they neared Yoksum, they hid in a forest above the village until night fell. Then they sneaked Kunsang to the big house, the house of Yab Maila and his brothers, one of whom was the head of security for the royal palace and another was collecting taxes for the king. Both of them had been asked by the king to be on the lookout for any suspicious activity. And here they were, hiding Kunsang from the king’s men.

They fed Kunsang and hid him in a back room until well after midnight. Then they disguised him and brought him a little out of the village to a cave where no one would ever think of looking. There he hid out while Yab Maila collected supplies of

tsampa

, corn and other food to be brought through the mountains to Tseram. While Kunsang lived in that cave, his father’s disciples who had stayed behind sneaked up to the cave bringing him all manner of food and homemade beer. The fear of being left behind when Tulshuk Lingpa opened the gate had grown to paranoiac dimensions. Many thought Kunsang had come secretly to tell Yab Maila and family that the time had come. As they plied him with goodies, he had to deny repeatedly and vociferously that he was there to tell Yab Maila and family of the opening. They extracted from him promises that they wouldn’t be left behind. ‘We have all hid provisions in caves along the way to Tseram, so we can meet you for the opening in no time. So remember to tell your father not to forget us. We’re ready!’

It took five days for Yab Maila to gather the sacks of provisions to be taken to Tseram without attracting attention and also to organize five discreet nomads who wouldn’t attract attention by carrying them to Dzongri and beyond. On the night before leaving they sneaked Kunsang down to Yab Maila’s house. There, behind closed doors with curtains drawn, they had a party with trusted disciples of his father and lots of drinking and dancing. It was to celebrate Kunsang’s last night in Sikkim before going to Beyul where he was sure to become prince. The occasion was a wild and happy one, though for Kunsang it was tinged with a bit of nostalgia and sadness.

At well after midnight Kunsang’s head was spinning from the homemade beer. They sneaked him out of Yoksum to where the five nomads were waiting. With sacks strapped to their backs, and by the light of the moon, they climbed into the high mountains.

After they climbed beyond Dzongri, they hid the sacks of food in a cave where no one would find them. One of the nomads decided Beyul was better than herding sheep and goats, so he pledged his herd to the others and went with Kunsang to Tseram. Later, Tulshuk Lingpa sent people to get the provisions.

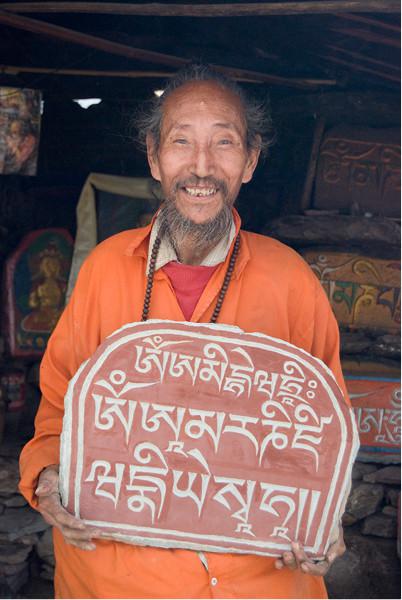

Garpa was living at Tashiding when Tulshuk Lingpa arrived and quickly became his disciple. Garpa still lives in Tashiding. His life work is carved on untold thousands of

mani

stones, the stones sculpted with mantras in Tibetan script. His workshop, a corrugated tin roof held up with wooden poles and backed up by a stone wall, is situated along the

kora

at the back of the monastery in a quiet corner behind the stupas, where the land drops off to a slope of pine trees. That’s where one can find him sitting cross-legged on an old burlap sack raising small puffs of rock dust by pounding the surface of a flat stone with a well-used but sharp chisel, allowing the mantra

Om Mani Padme Hung

to manifest. Garpa also sculpts reliefs of Buddhas and Tibetan deities.

The first time I met him, Garpa’s engaging smile assured me that my presence was not an intrusion. He indicated a block of wood beside him for me to sit on. I asked him how long he’d been carving stones at Tashiding. He asked to see my mala, or Tibetan rosary, hanging around my neck. He proceeded to turn the wooden beads between his thumb and forefinger one by one. I thought he was praying. Then he stopped. He handed the mala back to me, careful that I put my finger between the two beads he had reached. ‘That many,’ he said, and continued chiseling stone. I counted the beads. Garpa had been carving stones at Tashiding for forty-five years, since he fled with the Dalai Lama when the Chinese invaded Tibet in 1959.

Garpa’s clothes are simple. His manner is direct, and he is at ease. Though his work requires his fullest concentration—carving stone is clearly his form of meditation—being interrupted seems part of his daily round. Tashiding is a quiet place, and many of those doing the

kora

are Garpa’s neighbors and have been circling the monastery for an hour or two or more every day for decades. Garpa greets them like the old friends that they are and offers them a block of wood to sit on, pauses his work for some moments to exchange news, then continues coaxing Tibetan letters out of stone.

I found it soothing to become a forgotten presence at Garpa’s side, the hammer falling on the chisel with the regularity of the beating of a drum, the chisel carving the stone, the letters appearing. Though Garpa’s hands are bent with age, he wields his tools with the precision and artistry of a violinist drawing his bow.

Even once you realize that almost half a century of patient work has gone into carving the

mani

stones at Tashiding, it is difficult to believe they are the product of one man. Tashiding abounds with walls built entirely of his carved stones. He has carved so many

mani

stones that there are walls constructed of stones stacked together one on top of another so the lettering isn’t even visible. Yet even that which is carved in stone is impermanent. While his more recent works are still brightly painted, his earlier works are weathering with time.

Garpa

Garpa is neither a lama nor a monk. He has a wife and grown daughter who, together with his son-in-law, live with him in a house just outside the monastery grounds.

I asked Garpa how it felt, knowing that his stones would far outlast him.

‘How should it feel?’ he responded. ‘The beauty of the

mani

is not coming from me. The

mani

itself has the beauty in it. I only bring it out. This is what I do.’

I asked Garpa whether he has sponsors, people who pay for his work. ‘Occasionally,’ he said, ‘but it doesn’t matter whether I have a sponsor or not. My work is carving stone. This is my form of meditation, to get rid of all bad karma.

‘I’ve had two main sponsors in my life,’ he told me. ‘They were my root gurus, Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche and Chatral Rinpoche. Chatral Rinpoche is still alive. He is ninety-four years old. Every year he goes to the mouth of the Ganga below Calcutta and releases thousands of fish bound for the market into the sea. I started carving stones in Tibet before I fled the Chinese invasion. When I first arrived at Tashiding, I wasn’t very good. Chatral Rinpoche saw my work and invited me to his monastery outside Darjeeling for six or seven months. He taught me how to carve stones correctly. Since then I’ve also carved stones at his monastery, at the Pemayangtse Monastery here in Sikkim, and in Nepal.’