A Step Away from Paradise: A Tibetan Lama's Extraordinary Journey to a Land of Immortality (18 page)

Authors: Thomas Shor

‘Oh! Great and noble man! Though the negative forces burning with wrath might curse you, no harm can be caused to you by these evil spirits and demons. This is because of your pure heart and the strength of your noble aspirations. Since all things are empty and non-existent, you will live long and accumulate more merit, and your acts of benevolence will increase. However, you must be cautious not to associate with foolish people. Together with the retinue of your firm-hearted and devout followers, do your utmost to fight the forces that cause spiritual obstructions. Be sure to make offerings and to chant and pray as much as possible. Since you have accumulated much merit, you may go anywhere you like without fear. I will provide all the help you need to ward off impediments.’ As soon as he uttered these words, I woke up from my dream-like state.

For Tulshuk Lingpa, the landscape he passed through was only nominally of the early part of the sixth decade of the twentieth century. From Kullu, he and his retinue passed through Mandi which he refers to as ‘the palace of the Zahor king’, the Zahor king being the father of Padmasambhava’s consort in the eighth century who tried to burn him alive. They travelled 1200 miles by train east across the north Indian Plains, then reentered the Himalayas and went north towards Sikkim, stopping off just south of the kingdom at Kalimpong (which he calls Kalinka in the text) to see Dudjom Rinpoche, Tulshuk Lingpa’s root guru.

Chokshi, the young man responsible for bringing Tulshuk Lingpa to Simoling, was with Tulshuk Lingpa on this journey. He told me that they left secretly, and no one they met on their journey would have suspected the mission they were on—to lay the foundation for a journey to another world—or even that Tulshuk Lingpa was a lama. He wore regular clothes—only rarely would he wear robes—and his hair was long. When asked, they said they were on a pilgrimage.

Dudjom Rinpoche lived just outside the town of Kalimpong in the village of Madhuban. Chokshi described to me how Kalimpong was full of Tibetan refugees. Disoriented, frightened and traumatized by the brutality that prevailed a few days’ march away over the Jelepla, the main pass to Tibet on the Lhasa trade route, they were pouring into Kalimpong and other towns across the Indian Himalayas, living reminders of the importance of finding the beyul.

As they headed up the hill to Madhuban, then a small village on the edge of which Dudjom lived in a large British colonial house, they had a conversation that Chokshi told me went something like this:

‘Please, Master, we are going to meet a great lama. You are also a great lama. You cannot meet him wearing the old shirt and pants you’ve travelled in. Please, change into your robes.’

‘The clothes one wears don’t matter,’ Tulshuk Lingpa responded. ‘It is what’s inside that matters. Besides, it is always better not to show on the outside what one is inside.’

‘But Master, please, we are your disciples!’

Tulshuk Lingpa gave in to their entreaties, not because he was convinced they were correct but out of a sense of compassion. In the forest surrounding the village—Madhuban translates to Honey Forest—he took off his street clothes and put on his white robe.

Chokshi told me they spent three days with Dudjom Rinpoche, and that Tulshuk Lingpa disclosed to his master the reason for their journey, to investigate the vision he had had of Khandro Yeshe Tsogyal and the other signs he’d received along the way. Dudjom Rinpoche was himself a high terton, as well as a mature and learned lama.

Of his encounter with his guru, Tulshuk Lingpa wrote these lines: ‘He received me with a smiling countenance and addressed me thus, “Proceed. All the precious literary treasures and the prophecies of the Hidden Land of Demoshong are in conformity with your coming to this place.”’

Chokshi recalled that Dudjom also warned Tulshuk Lingpa to keep his mission secret and to take with him only people of unusual clarity and purity, and above all else to proceed slowly. He sensed in his young disciple an impatience that could prove troublesome. Time must mature before an opening can occur.

‘Those you take with you,’ Dudjom warned him, ‘will determine your success or failure. They will each have to leave everything behind, not only physically but in their inmost thoughts as well.’

From Madhuban they travelled a few hours to Jorbungalow, a small town near Darjeeling, and to the monastery of arguably the greatest Tibetan yogi practitioner of his day: Chatral Rinpoche. When Chatral Rinpoche heard Tulshuk Lingpa’s story, he gathered Tulshuk Lingpa’s disciples around him and read from a terma that was hidden by Padmasambhava and discovered long ago. It described Beyul in great detail.

Tulshuk Lingpa (R) with Chatrul Rinpoche

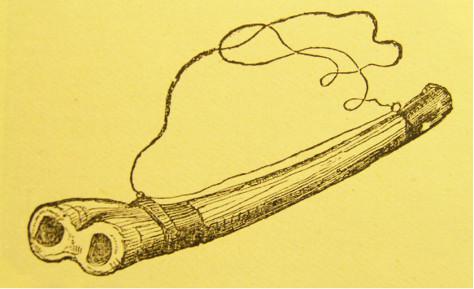

Then Chatral Rinpoche gave them some practical advice. ‘When you are in the high mountains to find the gate to Beyul, don’t make a fire at night. It will attract animals and spirits. Here, use this,’ and he gave them a human thighbone horn. ‘Blow this at night,’ he told them. ‘It will scare away the animals and keep the spirits from bothering you, too.’

“Trumpet made of a human thigh-bone”

from the

Himalayan Journals

of Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1891

On the third day they were there, Tenzing Norgay came to see Chatral Rinpoche. It was Tenzing Norgay who, a few years earlier, together with the New Zealander Edmund Hillary, was the first to scale the highest peak in the world, Mount Everest. It was a feat that made him both world-famous and, though he was born in Nepal, his adopted home Darjeeling’s favorite son. He came to Chatral Rinpoche because one of his two wives was very ill. The doctors were unable to heal her and he wanted the great lama, of whom Tenzing Norgay was both a disciple and a sponsor, to help her. When he presented his case to Chatral, the lama laughed: ‘You are very lucky you came today. If you would have come tomorrow, the man who could help your wife would be gone.’

He then introduced the great mountain climber to Tulshuk Lingpa, telling him that this was the lama with the greatest abilities to heal and that he should take him to his wife. So Tenzing Norgay took Tulshuk Lingpa and his small retinue to his house in Darjeeling, where they performed pujas and administered Tibetan herbs. Tenzing Norgay’s wife quickly recovered, which earned Tulshuk Lingpa both a new disciple and a sponsor. ‘Whenever you are in Darjeeling,’ he told Tulshuk Lingpa, ‘you must stay in my house,’ which Tulshuk Lingpa did. Tulshuk Lingpa kept secret from Tenzing Norgay the real reason for their journey: that they were investigating the way to Beyul. Dudjom’s warnings were fresh in his mind, and Tenzing Norgay was a gregarious, famous fellow who would not have kept the secret.

From Darjeeling, they went north to Sikkim to begin their investigations. Before Sikkim became a state of India in 1975, it was a separate country: a kingdom that traditionally had been closely aligned with Tibet. So when Tulshuk Lingpa and his followers travelled from Darjeeling down through the tea estates to the Rangeet River, which formed the border between India and Sikkim, they had to pass through an immigration checkpoint on the other side of the bridge. Since Tulshuk Lingpa was Tibetan and had passed into India on the sly, he didn’t have proper papers. Therefore a bit of careful negotiation was called for, which Tulshuk Lingpa accomplished in his typical tulshuk manner—with a bottle of liquor. This left him and the officials not only drunk but also friends. This would prove useful in the future.

In Tulshuk Lingpa’s account of this journey, he tells us that they arrived in the town of Singtam on the first day of the twelfth month, or 17 January. In Singtam, he writes, ‘Amid a tremendous confusion, I saw a hoard of gods and demons showing their likes and dislikes towards me. However, I took no interest in their doings.’

They proceeded further and, ‘I inquired from people the name of the place and the history of its beginning. However, since I could not understand the local language, I resorted to sorcery, and went straight to the much-famed holy and secret cave of the

dakinis

situated there.’

That evening Tulshuk Lingpa conducted an ‘internal fire offering’. Then, he tells us,

I fell into a light sleep in which the world of appearance turned into the shape of a triangle, in the center of which a red-faced young woman, both smiling and wrathful, carrying a vajra knife and a cup made of a human skull, addressed me thus:

Proceed, proceed to the Hidden Land,

Do not, do not split from the friends you like,

Do not, do not listen to fools without faith,

Do not, do not forget the prophecies of Padmasambhava,

Attain realization, realization for the good of all beings,

Torment, torment the gods and spirits into keeping their sacred oaths.

Make them, make them develop an altruistic attitude towards others.

Generate, generate pure thoughts.

It is possible, possible that the door of the sacred place will open again.

Having said that, she touched my lips to the nipples of her two breasts three times and declared that I had then fully obtained the blessings, initiations and transmissions of the three Buddha bodies of the

khandro

. Then, showering me with absolute love, she vanished into space. I woke up from my dream in perfect joy.

From the cave of the

dakinis

, they proceeded to the holy center of the kingdom, the Tashiding Monastery. Set on top of a mountain at the end of a ridge, which falls off to where two rivers merge, Tashiding has a 360-degree view of the surrounding mountains and earns its name well, for Tashiding means Auspicious Center. Tashiding is the ‘center’ of Sikkim the way the heart is the ‘center’ of one’s being.

It is said that Padmasambhava himself blessed the place. In those days one had to walk to Tashiding, skirting cliffs and fording rivers on footbridges through a spectacular landscape. Tulshuk Lingpa describes his meditation upon their arrival:

I had all round a feeling of total peace and happiness. This sense of utter happiness transformed itself into great compassion and the spontaneous manifestation of happiness. Towards the beings of the six realms and those of the present time, I developed an irresistible feeling of compassion. In such a mood—through my deep contemplation—whatever sights and sounds I experienced were turned into the body, speech and mind of Chenresig, the Buddha of Compassion. After getting up from this meditation, I offered prayers and benedictions in order to expand and maintain the clear light of sleep.

That evening I was visited by various

khandros

, one of whom made many extraordinary forecasts; another gave me books containing secret oral instructions as well as secret predictions and percepts.

Two days later, in the morning, Tulshuk Lingpa explored the area to ‘find out whether the place possessed any auspicious signs and marks’.

I offered prayers to the divine master of the place, and made an extensive examination of the whole area. Several signs and marks indicated auspicious and happy tidings. Being happy and cheerful, I offered the following words of praise, ‘Oh! Most wonderful is this place, Demojong, wonderful is the way of its formation. It is something like the blossoming of the broad leaf of the blue lotus.’