A Step Away from Paradise: A Tibetan Lama's Extraordinary Journey to a Land of Immortality (17 page)

Authors: Thomas Shor

He travelled to the western Himalayas with the wish and prayer of finding the lama who would open that place of shelter for all Tibetans. But along the way, the quest for survival came to dominate his existence and he found himself, like the hero of mythology, forgetting his quest from the sheer exhaustion of working on a road crew cracking rocks for the construction of the new road up the Kullu Valley. He lived below the road along the banks of the Beas River in a camp of makeshift lean-tos of sticks and river stone occupied by about a hundred of his colleagues, a mix of displaced Indian families, rootless wanderers and Tibetan refugees like himself.

Above their camp were huge cliffs, and he started hearing about a lama who lived in a cave up there. At first he heard he was a crazy and drunken lama. He was too tired after a day of cracking stones with a heavy hammer to climb the cliffs for such a lama. Besides, Zurmang was from Kham. No local lama could compare with a Khampa lama, he thought to himself, so he didn’t pay much attention to the news. But he kept hearing of this lama who lived in a cave, so he finally asked, ‘Who is this lama?’ When he heard that he was from Kham, he became interested. He grabbed the

pecha

and climbed to Tulshuk Lingpa’s cave.

Since Kunsang was there when this Khampa lama wearing a road laborer’s clothes and a

pecha

under his arm arrived at the cave, we have a first-hand account of what happened.

‘He was dirty,’ Kunsang told me, ‘and his clothes were covered in rock dust. The moment he opened his mouth, my father picked up on his distinctive Khampa dialect. So their conversation began commonly enough, my father started asking him the normal questions: Where are you from? What monastery did you study at—that sort of thing.

‘When the pleasantries were over, the lama started steering the conversation towards—of all things—Beyul Demoshong. I was surprised since it had always been my father who had been speaking of Beyul, saying he was going to lead the way; but now he was silent, as if he didn’t know a thing, and just let this lama talk. I could tell there was something up. With my father, there always was. I’ve always been thankful he let me—as his only son—partake in so many

interesting

situations. He was crazy—sure! But there was always another angle—a perspective from which it all made sense, in the end.

‘Then my father, in an almost casual way, let it slip that he had been visited by Khandro Yeshe Tsogyal. You should have seen the Khampa lama’s eyes widen. He looked at my father in a new way. I could tell he was weighing something, on the verge of both rejoicing and disbelief. The

pecha

he was carrying described the five attributes by which the lama who would open Beyul Demoshong could be recognized. Not only would he be discovered in the western Himalayas where we were but he was to be originally from Kham. There were four other attributes: he was to be tall, have long braided hair, have eyes like a tiger and be a

myonpa

—which translates to madman or crazy person.

‘As he looked at my father, you could practically see him ticking off the attributes one by one. When he got to the last he hesitated, until he considered my father’s name, the fissure in the cliff face where we were all sitting, and the fact that he lived there with his wife, daughter and son.

‘Zurmang Gelong decided to get closer to the point, so he asked my father whether he’d ever heard of Dorje Dechen Lingpa.

‘“Of course,” my father replied, “I knew him as a child. He’s the one who coronated me and gave me my name.”

‘It was with a trembling hand that Zurmang Gelong unwrapped the

pecha

from its cloth cover. He described the meeting of

tertons

and read a few lines of the

pecha’s

description of Beyul.

‘My father reached into a cleft in the rock wall and took down a

pecha

written in his own hand, which he had written after his encounter with Khandro Yeshe Tsogyal. He unwrapped it and read the same lines, word for word, dictated to him by Yeshe Tsogyal during his vision of her.

‘Zurmang Gelong pressed the

pecha

to his forehead with tears streaming down his cheeks. “When you go to Beyul,” he implored my father, “you must take me with you. I’ve been praying for this for so long. It has been my dream.”’

Increasingly, people flocked to Tulshuk Lingpa to hear him speak of Beyul.

Kunsang remembers his father saying, ‘One day I must go to Shangri-La. Whoever wants to come with me, come but only if you have no doubts. If you have doubts, please don’t go. Stay here!’ Kunsang remembers him saying this especially when some

jinda

provided him with a big bottle of something nice to drink. Tulshuk Lingpa got a reputation from this, as you can well imagine. Some thought him mad; others pressed him, continually. ‘When will we go, Master? When?’ It was especially the people from Simoling, those with the greatest faith in the one who had delivered them from disfigurement and death at the hand of the female cannibal demoness, who wanted to go with him. Even his closest disciples pressed him continuously. But for years, he held them off.

‘The time is not right,’ he would tell them. ‘We must do more pujas; we must be purified and ready. Not one doubt can enter our minds. Then we shall be ready.’

‘When my father spoke of Beyul,’ Kunsang told me, ‘he spoke in the language of the scriptures, which in Tibetan is not comprehensible to the common people. So they used to come to me, and ask what he was saying.’

Kunsang burst out laughing.

‘At the time I was just a kid, a teenager. They’d gather around me, eyes full of wonder, and because I was Tulshuk Lingpa’s only son they’d ask me how we were supposed to eat in the Hidden Land, how we’d get clothing and what the weather would be like. I told them that to get to that place we’d have to cross over some high altitudes but once we got there it would be quite hot in some places—and cold in others.

‘Then they’d tell me, “It is uncertain how long your father will live once we reach Shangri-La but after he dies, you will take over. You will certainly take out

ter

in the Hidden Land!” They didn’t understand that you didn’t die in the Hidden Land, and I didn’t correct them.

‘They’d ask me how we’d enter the Hidden Land, and I used to tell them that Beyul cannot be seen with the naked eye. There would be a huge stone with a stream flowing over it, and you would jump into the waterfall and come out the other side. Others thought Tulshuk Lingpa would get to Beyul first, and then throw down a rope. Later my father’s two closest disciples, Namdrol and Mipham, told me that what I had been saying wasn’t true. They said there was no waterfall. “The way to Beyul,” they told me, “is really difficult: all snow and ice.” It’s true. My father said his route would be the most difficult. I spoke of the waterfall because I had heard of another beyul called Pemako, some hundreds of miles east of Sikkim where the Tsang Po River descends through the Himalayas in a series of hidden waterfalls to become the Brahmaputra.’

‘What did you expect to happen once you entered Beyul,’ I asked Kunsang.

He made the thumbs up. ‘Happy,’ he said.

People often told me that Tulshuk Lingpa held the key to Beyul, and it wasn’t always clear that they didn’t mean it literally. The key grew in some people’s imaginations until it was the size of a crowbar that they expected Tulshuk Lingpa to thrust through a chink in the world around us in order to open a crack into another.

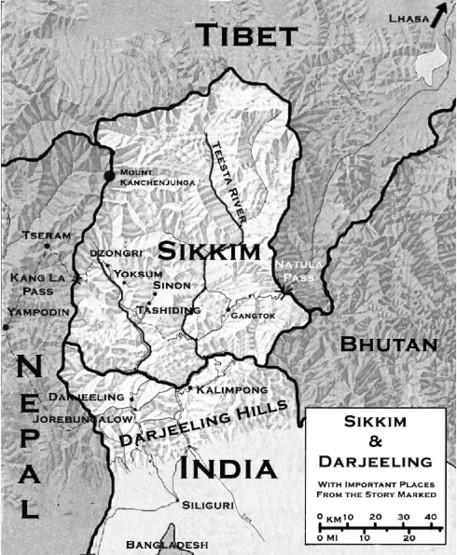

Map 2. Sikkim and Darjeeling, showing important places from the story

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER TEN

The Reconnaissance

In 1959, the Chinese culminated their brutal attack on Tibet by taking control of the once-forbidden city, the capital Lhasa. Pleading with his people not to respond with violence to the violence and brutality the Chinese meted out (estimates are that over a million were murdered by the Chinese before their takeover was complete), the Dalai Lama fled south over the Himalayas and found asylum in India.

When word of this reached Tulshuk Lingpa, he knew the Tibetan dharma and people were in graver danger than they had ever been in before, and that therefore the time was drawing close for the opening of Beyul Demoshong. Together with his consort and a few of his closest disciples, he made a journey to Sikkim in order to get a feel for the landscape and—as we shall see—to encounter various deities and guardian spirits.

We have unusual insight into the inner realizations and visions Tulshuk Lingpa experienced during this trip in the form of a

pecha

, or scripture, in which he wrote about it. The text, which he describes as a ‘song of the road’, is titled

The Creeper-Plant of the Mind

and it was given to me by Kunsang. It is here, in his own words, that we get a glimpse of the extent to which Tulshuk Lingpa was subject to visionary states, from which he gained his knowledge and experience of the beyul.

The time has reached the highly degenerate state of the final five hundred years, in which the armies of the barbarians destroy the peace and happiness of humanity, when the teachings of the Buddha are destroyed from their very foundation, reducing the happiness and prosperity of the world to the size of a sun ray on a mountain pass.

Listen to this story of how I went to Demojong [Sikkim], rendered into a song.

If you sincerely follow what I teach, you will certainly be happy. Whatever I do, I do it not for my own interest. Nourishing the desire for the good and welfare of the many, I am little concerned with what others do—or with whether they praise or insult me.

Tulshuk Lingpa gives the exact day he set out with his small band of disciples:

In the evening of the twenty-first day of the eleventh month of the Iron Male Mouse year [Sunday, January 8, 1961], the year that was said to be harmonious with the four elements, I left my home in Pangao and went to the capital, Kulluta.

Kulluta is the local Buddhist name for the town of Kullu, the administrative center of the district, a rather large town about thirty miles south of Pangao.

One evening when I was in a mixed state of sleep and the true nature of mind, the deity Dorje Lekpa (a

dharmapala

) appeared before me in the guise of a monk. He smiled at me and addressed me thus: