A Step Away from Paradise: A Tibetan Lama's Extraordinary Journey to a Land of Immortality (21 page)

Authors: Thomas Shor

‘Look,’ he said, ‘a perfect signal!’

It was true. He quickly called Delhi. When he got his girlfriend on the other end, he stepped out of the door of Géshipa’s room on to the old wooden staircase for some privacy but the signal faded the moment he crossed the threshold of Géshipa’s room. The only place during that entire trip where his mobile phone worked was inside the room of that wizard.

The third time I went to Yoksum to visit Géshipa, I went with both Kunsang and Wangchuk. Kunsang and Géshipa hadn’t met in over forty years. When we arrived this time, the rickety wooden staircase leading to Géshipa’s room above the cows was full of black dogs—thirteen to be exact—who started barking and howling at us and blocking our way. Since their barking was accompanied by wagging tails, they seemed harmless enough; we pushed by them and into Géshipa’s room.

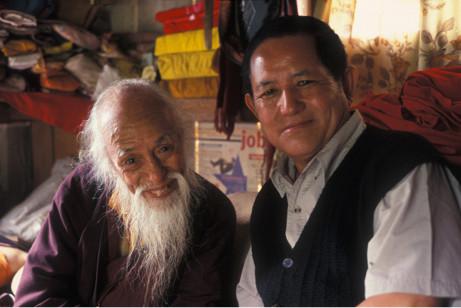

Géshipa and Kunsang, Yoksum, West Sikkim

After Kunsang and Géshipa exchanged greetings and comments on how the other looked—such as was natural for the first meeting in over forty years (Géshipa was in his late forties and Kunsang eighteen when last they met)—I asked Géshipa why there were so many black dogs guarding his door.

‘It is because of the

dip shing

,’ he replied.

I asked my faithful interpreter Wangchuk what

dip shing

was. He didn’t know, so he asked his father.

Kunsang knew well.

‘

Dip shing

isn’t known to all lamas,’ he said. ‘It is known only to

tertons

. It is a potion for becoming invisible. I remember my father teaching Géshipa, Namdrol and Mipham about it. But you need some ingredients that are very difficult to obtain. Géshipa has been working on this for decades.’

Géshipa just started speaking, and it was all Wangchuk could do to keep up with the translation.

‘The black dogs are a long story,’ Géshipa began. ‘I lived in Tashiding until about two years ago. Ever since the time Tulshuk Lingpa was here I’ve been collecting the ingredients. Some of the ingredients are easy to find, like the afterbirth of a black cat. Namdrol had that. He dried it, and had it with him all the time in a little pouch tied to a fold of his robe. He had it with him when we went to open Beyul.

‘The hardest ingredient to get is top secret, and I cannot talk about it.’ He then proceeded to speak of it with Kunsang but in such low tones that Wangchuk couldn’t catch what he was saying.

After some moments of this top-secret association, Géshipa sprang up on his bed with surprising agility for someone his age, and took a scripture wrapped in cloth and sealed to its dusty shelf with an intricate lace of cobwebs. He sat back down, unwrapped it, searched for the right page and started reading softly to Kunsang about this secret ingredient, which Wangchuk thought might be of human origin.

Then Géshipa continued in a louder voice and Wangchuk resumed interpreting: ‘The second-most difficult ingredient to find gives this potion its name. It is also the most important: the crows’ nest. You need the twigs from a crows’ nest but only from a very special crows’ nest.’

Wangchuk whispered in my ear that

dip shing

literally means invisibility stick in Tibetan, the stick in question being the kind with which a crows’ nest is constructed.

‘There was a boy in the neighborhood,’ Géshipa continued, ‘who was always climbing trees. I took him with me and we walked from Tashiding up to Ravangla. This was years ago. We went into the huge, ancient forest on the mountain above the town and we walked until we heard crows in the distance. We followed the sound until we saw the crows. Then we followed them until we were on the backside of the mountain and after three or four days we found where they made their nests high up in the trees. I had brought the boy because he climbed like a monkey. I sent him up with a rope to get a nest. The rope was for him to tie himself to the trunk before he climbed out on to the branch. But he refused to use the rope. The more I insisted, the higher he climbed out of my reach and started swinging from branch to branch laughing at me.

‘He scampered up to the crows’ nest, disturbing the crows who let out a raucous chorus of impotent protest. I yelled up to him to make sure the crows were completely black. Sometimes crows can have purple tails or wings, you see, and these won’t do. He assured me of their black color. So I told him to take the nest from the tree and bring it down.

‘The nest was practically as big as the boy, made out of hundreds of sticks. I started examining it but the boy said we should hide it, so no one could see what we were doing. Though there was no one else there, he was right. These are secret things. Tantra. So we put the nest in a sack.

‘We slept in the forest again that night, and in the morning we walked down to the river. It isn’t just any stick from a black crows’ nest that will work in the potion of invisibility. You have to test it.

‘So we went to the river’s edge. It was really a mountain stream, bounding down the mountain but the flow was swift and it would do. I broke off a piece of the nest, a stick about three inches long, and I dropped it into the flow. The boy had no idea why I was doing this but what he saw sure made him stare with wide eyes. For the stick hit the surface of the swiftly moving flow and moved

upstream

! This was exactly what it had to do if the nest had powers. The boy broke off another piece of the nest and tried it himself.

‘“Stop!” I shouted. “We were lucky to find such a nest. Others have spent years looking. Don’t waste it!”

‘But the boy kept breaking off pieces of the nest, throwing them into the stream and watching them float against the stream’s current—eyes full of wonder—until I grabbed the nest, threw it back in the sack and started back up the slope towards Tashiding.

‘When we got to Tashiding, I put the nest into the metal chest under my bed with the other ingredients. As you can see, it isn’t easy collecting the ingredients for the

dip shing

—though once I had the crows’ nest, the black cat’s afterbirth was easy.’

‘Sure,’ I quipped to Wangchuk under my breath, ‘You just have to find a black cat, get it pregnant—and wait.’

Géshipa, though not understanding what I’d said to Wangchuk, laughed along. Then he continued, ‘The

dip shing

takes years. But it is worth it. In the end, you apply just a little bit like a black paste on the forehead between the eyes—and like that, you’re invisible.’

‘One can make a potion to become invisible,’ I said, ‘but it’s another thing if it really works.’

‘Working,’ Kunsang said curtly in English, as if to put a complete stop to any doubt. ‘You need piece of crow nest. Black-cat-born-time.’

‘He means the afterbirth of a black cat,’ Wangchuk interpreted.

‘Two things, these ones,’ Kunsang continued, ‘and third is black cat shit. Fourth one, very useful but top secret. I know but cannot say. I putting little inside my bag, then tying bag to one shoe. Doing mantra, then my bag is—I-am-losing. Everybody notice bag gone; they no see, I no see.’

‘Tied to shoe?’ I asked Wangchuk. ‘What the hell is he talking about?’

I was beginning to feel as if I’d entered the land of topsy-turvy.

Wangchuk had grown up the son of his father, grandson of perhaps the craziest treasure revealer Tibet had ever produced, and could understand the language of wizardry. Yet he came down solidly on the side of his generation. Skeptical, rational and modern in outlook, Wangchuk was not only a good interpreter but a bridger of worlds. He respected, though not necessarily followed, the ways of his ancestors.

‘Tied to shoe,’ Wangchuk explained, ‘so you don’t lose the bag when it goes invisible.’

‘Yes, yes!’ Kunsang concurred, ‘Only string seeing. If not tied, losing bag. Crows’ nest

very

powerful.’

‘Let me get this straight,’ I said. ‘You need a piece of a black crows’ nest and a twig that goes upstream when put in water. That twig. And then you need black cat afterbirth.’

‘Oh, this one very important!’ Kunsang exclaimed. ‘Third one, shit of black cat.’

He then said something to Géshipa in Tibetan about black cat shit, and Géshipa started telling the story of how he secured his supply.

Wangchuk interpreted:

‘Since I did not own a black cat, I went into the village looking. I am not so young, so it wasn’t easy. Seeing a black cat behind someone’s house, I chased after it and caught it with my own hands. I caught it, put it in a sack and brought it home. I tied its leg to a string to wait for it to shit. But in the morning, the string was broken and the cat was gone. It had climbed a tree nearby and was meowing. The string had gotten wrapped around a branch. It was stuck there. So I sat under the tree, waiting. I knew it would have to shit sooner or later, and sure enough after a few hours I saw it drop. I scooped it up and got the boy to climb the tree and free the cat. Black cat not important—black cat shit important!’

‘So that’s the third,’ I said to Kunsang. ‘The fourth, what’s the fourth?’ I was trying to trick Kunsang into divulging the secret ingredient.

‘Fourth one is—’ Kunsang said, catching himself. ‘Fourth one I forget. Géshipa show me in book. But I don’t know. He know; he know.’

‘You just said you know,’ I shot back. ‘You said, “I know but I cannot tell.” Now you say you don’t know.’

‘I don’t know, really. He know. I forget but he show in book. Difficult to find. Very difficult!’

‘Can a person also go invisible?’

‘Sure thing! Then nobody will see you.

Kema

,

kema

: incredible! I don’t do this kind of work. Fourth thing, very difficult to find. Géshipa found it.’

‘Why would you want to go invisible?’ I asked.

‘Sometimes necessary.’

‘Why? To hide from the police? What did you do?’

Laughter.

‘Have you gone invisible before?’

‘No.’

‘Do you know people who have?’

‘No. Only stories.’

‘The fourth ingredient is from human beings?’

‘No, no, no—I forget.’

‘You don’t want to say?’

‘Géshipa had the secret ingredient,’ Kunsang said. ‘I remember years ago, Géshipa telling me, “If one day I go to the Hidden Valley, I’ll bring one small leather bag with everything in it—snake meat, frog meat, all dried. Black cat, too, all dry. Black dog meat, dry. I’ll make everything dry and take it with me.” But what to do? He had everything. He even had elephant liver, cut in little pieces. But all stolen.’

‘Stolen?’

‘Yes,’ Kunsang said. ‘Stolen.’

‘What happened? Wangchuk, ask Géshipa what happened.’

‘It had taken years to collect,’ Géshipa said, ‘and I had almost all the ingredients. I was living at the Tashiding Monastery in those days. As I got each ingredient, I put it into the locked metal box under my bed. Then, one day I went to put something else into the box and the box was gone. It hadn’t gone invisible; it was stolen, along with one hundred and fifty rupees. So I had to start all over again. That’s why there are so many black dogs at my door.’

I couldn’t divine the connection. It had been my first and, I thought, quite innocent question. So I asked again, almost in desperation, ‘But why all the black dogs?’

Géshipa got up from where he had been sitting cross-legged on his bed to squat on his haunches before his kerosene cooker and start a fire for tea. He poured water into a pot, opened a can of tea and threw in a huge handful. Taking a flat rock off the top of another rusted old can, he reached his hand in and threw handfuls of large-grained sugar into the water as well, oblivious of the ants that had been feeding on it.

Géshipa spoke so matter-of-factly of fantastic things that one could easily imagine their reality. There was gentleness in him, an innocence that was alien to any sort of guile. He lived with the simplicity of a man for whom the material world around him was of so little concern because the scope of his creative imagination was so immense. His eyes were at once innocent and deep. They sparkled as if they wanted to communicate what no words could—the accumulated wonder of their eighty-six years of looking on a world that was just plainly more fantastic than the world most of us look upon.