A Step Away from Paradise: A Tibetan Lama's Extraordinary Journey to a Land of Immortality (13 page)

Authors: Thomas Shor

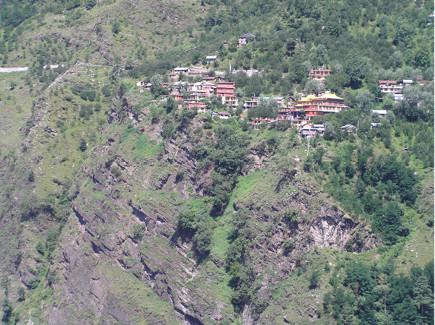

Tulshuk Lingpa lived in a cave along these cliffs.

The monastery didn’t exist in his time.

Pangao, Kullu Valley

Kunsang told me that when Jinda Wangchuk would come to his father, he’d always have two bottles of liquor in his pockets. He used to say, ‘One for the master, one for me.’

‘Even though I was only a boy,’ Kunsang said, ‘I’d say to Jinda Wangchuk, “One bottle for my father, yeah. One for him but one for you—no. Me, you, half-half.” Then Jinda Wangchuk would say, “Why not?” and share his bottle with me.’

In the course of writing this book, I found myself below the village of Pangao, crossing the cliff face to the cave where Tulshuk Lingpa and his family lived over the course of a decade. Following a monk who beat the grass and bushes before us with a long stick to flush out any cobras, I negotiated the treacherous, razor-thin way. My heart was beating to the rhythm of vertigo, my mind reeling with the consequences of one slip of the foot (a deathly plunge into the raging Beas River flowing like a ribbon of shining mercury far below). I couldn’t help but smile at the sheer divinely inspired madness of the man who would move his young family to such a place.

Pangao Cave, overlooking the Beas River

Kunsang recalled for me how twice a year they would make the three-day journey over the Rohtang Pass from Pangao to Simoling and back again. His mother and father each rode a horse and the kids walked, though they took turns riding when they grew tired. They followed the caravan route. They made the yearly migration from their high summer home to their winter home when the sheep and goat herders were driving animals over the Rohtang Pass to and from their summer grazing grounds on the high slopes of Lahaul. Therefore they often travelled surrounded by huge herds of sheep driven by herders dressed in heavy white woolen robes tied at the waist. Sometimes they would stop with the herders as their dogs circled their flocks and drank tea with them in the crisp and thin mountain air.

During these years, when Tulshuk Lingpa and his family went from Simoling to Pangao and back again, these two places became magnets for many of the great yogi lamas of the day. Some were obscure, others famous, and yet others were to become so. Some came as his disciples, others as his equals.

One of these Tibetan lamas, who was and is one of the great yogi practitioners remaining from the Tibetan tradition, is Chatral Rinpoche. He used to visit Tulshuk Lingpa in Pangao, and spent one winter in a neighboring cave on the same cliff face.

Tarthang Tulku was twenty-five when his native Golok was taken over by the Chinese. He fled to India, where he ended up in Lahaul, at Tulshuk Lingpa’s monastery. He travelled with him to Pangao as well, and later lived in a monastery down the valley from Simoling in Keylong. He then went for further studies to Sarnath. After that he moved to America where he started the Tibetan Aid Project, which helps Tibetan refugees as well as the Nyingma Institute and Dharma Publishing, which has published and distributed millions of copies of Tibetan texts.

Herbert Günther, the well-known German scholar of Tibetan Buddhism, also spent time with Tulshuk Lingpa. Kunsang remembers that when Dr Günther came to the Kullu Valley to pursue his studies of Tibetan religion and scriptures he stayed at the house of a big landlord who was a former colonel in the Indian army and a sponsor of Tulshuk Lingpa. He had bungalows in Manali, Kullu and Keylong. This thakur, or landowner, introduced Günther to Tulshuk Lingpa. Günther recognized Tulshuk Lingpa’s great learning and, while probably not becoming a disciple, was his student for quite some time in both Pangao and Simoling.

‘My father was always joking,’ Kunsang told me. ‘He used to say that because Dr Günther didn’t need a translator, he was a

tulku

, an incarnation. Günther was very good at reading and writing Tibetan, though sometimes my father would help him with his grammar. To me, Dr Günther was very old, though if I think back he must have been only forty-five or fifty. He would write his questions out in Tibetan, and my father would answer them.’

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER EIGHT

The Call

Kunsang had brought me through this much of his father’s story when he suddenly said, ‘Up to this point there was nothing

unusual

about my father.’

The cup of hot tea the Tamang Tulku had just handed me almost slipped from my hand, which so amused Kunsang that it took him some time to stop laughing and to explain: ‘My father was a terton, of course. He had that ability—but so have many others since the time of Padmasambhava.’

I got his point, which was one of perspective. Tibet has, after all, produced many highly developed mystics.

‘Up to this point,’ Kunsang continued, ‘if you were writing a book about my father, what would you have described? A few incidents, the finding of

ter

—but others have found

ter

. He led an army but there have been wars since the beginning of time and no lack of people to lead them. If that were all, if he had gone on being a village lama, you wouldn’t be writing a book about him.’

I had to nod my head in agreement, and wonder what he was getting at.

‘My father was gifted in many arts,’ Kunsang said, ‘not least of which was healing. As a visionary, he communicated between worlds. Whatever he did, there was a shine. Yet up to this point, his life’s work hadn’t even been announced. Each terton has his particular set of treasures

to uncover—be they texts, teachings or objects of great strength. Few, even among the

tertons

, have the destiny to discover a Heaven on Earth.

‘Until now, my father had shown a tremendous ability to communicate with the hidden world of the spirits and to intercede in hidden processes for the benefit of those who came to him. His actions were marked by a sense of compassion. He developed fully the nature of the name that Dorje Dechen Lingpa bestowed upon him. Yet what was changeable and unpredictable in his outward behavior, what appeared inconsistent, capricious and erratic, was but the outward appearance of a man whose mind was attuned to other things, and who was a visionary.

‘Despite being a visionary who was tuned to the inner world to a greater degree than most, he was not oblivious to the outer world, not even to the world of politics. For shortly after the Chinese invaded Tibet in 1951 and marched through his native Golok, in eastern Tibet, on their way to the Tibetan capital of Lhasa, stories drifted like a miasma over the mountains from the Tibetan Plateau beyond, stories of the massacres and suffering caused by the invasion. He immediately foresaw the consequences—the Chinese takeover, the carnage, the smashing of the monasteries, the imprisonment of monks and lamas and the flight of the Dalai Lama.

‘In fact, Tulshuk Lingpa predicted troubles for the fourteenth Dalai Lama twenty years before he fled. This was before my father came to India, when he was in Lhasa with lamas from the Dalai Lama’s monastery. The present incarnation of the Dalai Lama, the fourteenth, was yet to be found. Tulshuk Lingpa told these lamas that he didn’t think when they found the boy that the boy’s future would be good. “Shut up!” they said. “You mustn’t speak like that about His Holiness.” Some years later, those same lamas found themselves in exile along with the Dalai Lama. Tulshuk Lingpa ran into one of them in India and asked if he remembered his earlier prediction. Pressing his palms to his forehead and bowing, the lama silently acknowledged both Tulshuk Lingpa’s foresight and the tragedy of its coming to pass.

‘Tulshuk Lingpa saw the deteriorated condition of Tibet first hand when he returned there to rescue his parents. With a few of his closest disciples, among them Namdrol and Sookshen, he travelled across north India to the Kingdom of Sikkim and crossed the Nathula Pass to the Chumbi Valley in Tibet. They went to Dromo, where his parents had been waiting with two nieces and a nephew for five months.’

Tulshuk Lingpa’s father, Kyechok Lingpa, was a formidable character. A

lingpa

himself—wearing the white robes of a

nagpa

, his hair twisted in a huge bun on top of his head—he had been part of the Domang Gompa and had never had a monastery of his own. Now he received his own

gompa

in Patanam, a few days’ walk up the valley from Simoling. His wife, Kilo, was no less formidable. In Kunsang’s words, ‘She was huge, like a woman from Iraq–Iran.’

Tulshuk Lingpa’s father, Kyemchog Lingpa

It was in October or November some years later that they were in Simoling getting ready to make their yearly migration to Pangao when they got word that Kyechok Lingpa had died. Tulshuk Lingpa and his family went by horse to Patanam and Tulshuk Lingpa oversaw the cremation of his father. When the death ceremonies were through, he brought his mother back with him to live in Simoling and Pangao. Though his father’s followers made countless requests for him to come to Patanam to perform rituals there, he never returned. ‘If you need help,’ he told them, ‘you can always come to Simoling.’

The Chinese invasion of Tibet affected Tulshuk Lingpa profoundly. Not only did he see it for himself when he went to get his parents but with the continual flood of refugees from Tibet coming through Ladakh and Lahaul on their way to Kullu and beyond, he heard of the increasingly dire conditions. The dharma itself was in danger. The Chinese were smashing monasteries and torturing lamas, throwing them into jail and killing them.

To a yogi and mystic such as Tulshuk Lingpa, the most important thing is having the time and space to do spiritual practice. Tibet, with its vast isolation and empty spaces, had been a natural place of spiritual attainment; it had produced many of the world’s most highly developed mystics who had handed down and preserved an ancient tradition of attaining spiritual understanding and

bodhichitta

, loving kindness. In the isolation of the cliff face in Pangao and in the monastery in Simoling, Tulshuk Lingpa found that even surrounded by family he could continue to develop his practice. Yet he saw that for so many others death and cataclysm was their lot, and increasingly they had nowhere to go.