Read A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal Online

Authors: Michael Preston Diana Preston

Tags: #History, #India, #Architecture

A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal (28 page)

*

The tradition continues today. A vast tomb complex for the Ayatollah Khomeini, the biggest in Islam, is being built just outside Tehran. However, it lacks the opulence of some of its forerunners. By the ayatollah’s decree only utilitarian materials are being used in the construction and the great dome is of concrete.

*

Versions of the double-dome design were also adopted in Europe – for example, Filippo Brunelleschi used it for the cathedral dome of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence and Christopher Wren in his designs for the dome of London’s St Paul’s Cathedral.

*

Sir Christopher Wren was unusual in that he moved to architecture from science, the discipline in which he had received his only formal training.

*

The ‘Thugs’ were a sect of highway murderers who infiltrated themselves into groups of travellers and after a day or two ritually strangled their companions with a yellow silk handkerchief, mutilated their bodies and stole their possessions. In English the word ‘thug’ soon came to mean any brutal hooligan.

10

‘The Builder Could Not

Have Been of This Earth’

M

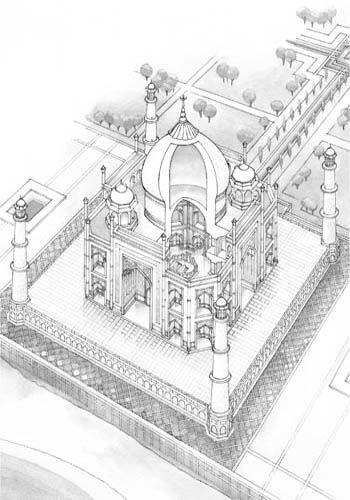

umtaz’s ‘illumined tomb’ was, Shah Jahan and his architects decided, to be the heart of a much larger complex. The mausoleum itself, at the centre of which she would be buried following Islamic tradition – lying north–south, with her face turned westwards to Mecca – would sit on a terrace or platform by the riverside within a walled garden. A water channel, also running north–south on exactly the same line on which Mumtaz’s body lay, would form a central axis, on both sides of which matching subsidiary buildings and other features would be laid out symmetrically.

Directly to the west of the mausoleum, on the platform, they placed a three-domed mosque, where pilgrims could worship. The Koran does not stipulate that a Muslim must visit a mosque to pray; he or she may pray anywhere, but to do so must face Mecca. An alcove, known as the

mihrab

, in the back wall marks the direction of prayer in a mosque. To balance the mosque opposite, or, as the Moghuls themselves put it, to serve as its

jabab

, or ‘echo’, the designers added a building identical to the mosque, directly to the mausoleum’s east. Since its rear wall faced away from Mecca, this building could not be used as a mosque – and probably served as a guesthouse for pilgrims – but its main purpose was aesthetic.

For the other end of the walled garden, facing the mausoleum, the designers planned an ornate gatehouse. Outside this gateway, to the south, would be an assembly area or forecourt known as a

jilau khana

, with accommodation for attendants and bazaars around its sides. Finally, beyond that would be caravanserais, or inns for visitors, and further bazaars, again all laid out symmetrically on either side of a central thoroughfare continuing the north–south axis provided by the main water channel. The whole area beyond the gateway would form a secular counterpart to the mausoleum compound, meeting the physical needs of the workers and visitors for food and accommodation, while the mausoleum complex nourished their spirits. The walled enclosure embracing the mausoleum and the garden would alone measure some 1,000 by 1,800 feet and was intended, in the words of Lahori, to

‘evoke a vision of the heavenly gardens … and epitomize the holy abodes of paradise’

.

In turning the concept into a detailed design, the Moghul architects had no design manuals or architectural textbooks to help them. Like other architects in the Islamic world they were guided by example rather than precept, drawing on the Moghul tradition of tomb building with its strong central Asian and Persian influences. In addition they assimilated much from the strain of Muslim architecture introduced into India by the Sultans of Delhi during their 300-year rule and by other Muslim rulers such as those of Gujarat and Mandu. They also drew on the Hindu architectural tradition, from which many of those doing the building work came, for features such as the domed kiosk, or

chattri

, finials and the use of intricate stone carving.

By contrast, Hindu builders had available to them treatises on buildings covering such matters as soil type and its identification by colour, scent and smell, techniques of brick masonry, the configuration of buildings and the most auspicious times to undertake various stages of the building work. These textbooks were not among the very many Hindu works of all kinds translated, on the orders of Akbar and his successors, into Persian and there is no evidence that they were ever used by Moghul architects. However, the Hindus among the builders would almost certainly have consulted them to interpret and implement the plans passed to them by the architects.

In seeking examples that might influence their design, the Moghul architects would have known that their predecessors in Persia and central Asia and in the Delhi Sultanate had used an octagonal ground plan in many buildings, including both palaces and tombs such as that at Sultaniya. An Italian merchant who visited Tabriz in Persia in the early sixteenth century described a now disappeared palace as called

‘“Astibisti” which in our tongue signifies eight parts as it has eight divisions’

. Architectural historians also point to the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, bathhouses in Damascus and palaces in Constantinople as conforming to this ground plan. They believe that the plan had its origins in pre-Islamic times, although to the Moghuls and their Muslim ancestors the octagon that resulted from the squaring of the circle had become a metaphor for the reconciliation of the material side of man, represented by the square, with the circle of eternity.

Abul Fazl describes how Humayun employed an octagonal design in a floating palace on the Jumna. His builders joined four two-storey pavilions, each floating on a barge, by arches to form an octagonal central pool. (Humayun even had other barges planted with flowers and trees to provide a garden setting for his floating palace.) The earliest surviving examples of the use of octagonal design in Moghul India are two tombs built in Delhi, probably between 1530 and 1550. Because who is buried within them is now unknown, they are simply called the Sabz Burj, ‘Green Tower’, and Nila Gumbad, ‘Blue Dome’, from their original tiling. (The former is particularly important in the genealogy of the Taj Mahal and is disconcertingly now tiled in blue. It is also sited in the middle of a busy roundabout.) Both buildings have eight small chambers surrounding an octagonal central tomb area with a dome above. The eight chambers are said to represent the eight divisions of the Koran.

Variations and developments of such octagonal designs – rather confusingly sometimes known as ‘the nine-fold plan’, from the number of chambers including the central chamber – are the basis for many Moghul buildings, including palaces as well as tombs, such as that of Humayun in Delhi constructed in the 1560s. For the Taj Mahal, the architects chose as their concept for the mausoleum a cube with its vertical corners chamfered to produce an octagon, with the cenotaph in a central octagonal space surrounded by eight inter-connecting spaces on each of two levels. For each of the eight exterior façades of the mausoleum the architects planned two storeys of arched recesses. On the four main sides, these recesses would flank massive entrance arches or

iwans

, similar to those on Humayun’s tomb, whose top border would rise higher than the rest of the façade.

The Sabz Burj is also the earliest surviving Moghul building in India to incorporate the double dome used in Timur’s mausoleum in Samarkand, although the design, which originated in Persia, had been employed in the tomb of one of the Delhi sultans a few years earlier. In Humayun’s double-domed tomb, the half-grapefruit-shaped outer dome and its lower inner one sit on a relatively low drum. In the Taj Mahal, one of the architects’ greatest achievements was to produce an elegant double-dome design for the mausoleum. The inner dome, which rises eighty feet above the floor, is in harmony with the scale of the rest of the interior and produces a resonant echo. The swelling outer dome sits upon a high drum and is in perfect proportion to the remainder of the exterior of the complex. Shah Jahan’s chroniclers described the outer dome as

‘of heavenly rank’ when complete and as ‘shaped like a guava’

– a fruit only recently introduced into India from the New World. Others have likened it to a flower bulb, a ripe pear, a fig, a bead of liquid or even a woman’s breast.

The architects surrounded the main dome with four domed kiosks. Although such

chattris

were used in Humayun’s tomb, there they seem too detached from the main dome. In the Taj Mahal, the architects placed them so that they cluster around the dome, seeming, from eye level, to be attached to it and softening the outline of the drum. Mindful of Shah Jahan’s love of jewellery, some have seen them as the minor stones, or even the claws, of a ring in which the dome is the major jewel.

The architects also added to the plan a plinth to raise the mausoleum itself above its riverside platform and positioned four circular white marble minarets, one at each corner of the plinth. Built on octagonal bases, the tapering minarets would have an interior staircase and three storeys, on each of which a balcony supported on brackets would cast shadows on the minaret in the sun. The minarets would rise to some 139 feet and each would be topped with an octagonal

chattri

. Although a minaret has the practical advantage in a mosque of providing a place for the call to prayer, they are not essential and, indeed, are not found in early Islamic holy buildings such as the Dome of the Rock. Their first use in a mosque in Damascus in the early eighth century probably resulted from the incorporation of the corner towers of a Roman temple previously on the site.

Schematic of Mumtaz’s mausoleum on its marble plinth

.

By the seventeenth century, at least a single minaret was general in mosques but not in mausolea or other religious buildings. Among the designs from which the architects may have drawn inspiration were the four towers on the gateway to Akbar’s tomb at Sikandra, the towers on the jewel of a tomb in Agra of Mumtaz’s grandfather Itimad-ud-daula and those at each corner of Jahangir’s mausoleum in Lahore. When they were built, one of Shah Jahan’s chroniclers described the Taj’s minarets as

‘like ladders reaching towards the heavens’

and another as like

‘accepted prayers from a holy person ascended to the skies’

.