A Thousand Sisters (11 page)

Read A Thousand Sisters Online

Authors: Lisa Shannon

The littlest girl excuses herself to go to the bathroom.

“I want to go out,” Luc says, startling me with his English, but continuing in Kinyarwanda. “I want to pee.”

That leaves only Noella. I sit down next to her on the bed. “My niece is like you, your age,” I say. “She's thirteen.” I show her Aria's picture. “I hope you find your parents very soon.”

She looks indifferent, moves with the slow, defensiveness of an animal under threat.

“What do you hope for in the future?”

“I want to be a child forever.”

OUTSIDE ON THE STEPS, the boys again crowd around me as I show them photos and postcards from home. Maurice translates, “They encourage you in your job. You are doing a good thing.”

One boy points to a photo of my niece, taken when she was ten years old, and says, “What about her breasts?”

“I don't want to talk about that,” I reply curtly. “Clean your mind.”

Then I look at Noella.

The next day, when I come back, her little girlfriend is gone; she's been sent home to reunite with her family. Noella is now the only girl here. She holds Serge's hand as we wander around the compound. While I take photos and look at boys' sketchbooks filled with drawings of guns and military uniforms, I note the paths to the bathrooms, the little corners of the compound, and I keep checking back in on Noella, tracking her on the periphery of the crowd.

I ask Murahbazi, “Do you really think it's safe to keep a young girl with all those boys?”

Those boys with the habit to kill, among other, um,

habits.

habits.

From Murhabazi's long pause and stare, it is clear I've overstepped. “She has a separate room. We have female staff. She's okay.”

CHAPTER NINE

When I Cry

MARIE, A GIRL

about seven years old, with kinky braids bent like wiry antennae and a big gap in her toothy smile, sizes me and my camera up from across the walkway. She is standing among the scraggly rose bushes that line the corridor, with the women in bold African print dresses, waiting. She seems oblivious of the gravity of this place and of her status in it as Panzi Hospital's youngest victim of fistula from gang rape. For a moment I contemplate filming or interviewing her. I conclude,

No way

. I hide the camera. The little girl returns to bouncing around in her party skirt, visiting with the nurses.

about seven years old, with kinky braids bent like wiry antennae and a big gap in her toothy smile, sizes me and my camera up from across the walkway. She is standing among the scraggly rose bushes that line the corridor, with the women in bold African print dresses, waiting. She seems oblivious of the gravity of this place and of her status in it as Panzi Hospital's youngest victim of fistula from gang rape. For a moment I contemplate filming or interviewing her. I conclude,

No way

. I hide the camera. The little girl returns to bouncing around in her party skirt, visiting with the nurses.

If Congo is the worst place on earth to be a woman, then Panzi Hospital is sexual-violence ground zero. Kelly has joined me to visit this high-profile treatment center for traumatic fistula, which occurs when the wall separating the vagina from the bowels or urinary tract is punctured and cannot heal. The damage creates a steady, uncontrollable leakage of urine or fecal matter. The victim smells bad, causing her to be rejected by her family and community. In most of the world, fistula can occur as a rare complication during childbirth. In Congo, traumatic fistula is a common form of sexual torture, inflicted with guns, tree branches, or broken bottles.

I do notice a bad smell, now that we are standing outside the fistula

ward. Dr. Roger, a slender man in a white doctor's coat who carries himself with a quiet elegance, has led us through Panzi's outdoor walkways and neatly cut lawns, past the “bad fed” (malnourished) children, the rows of male patients with bandaged gunshot wounds, the maternity and C-section wards, and finally, here, to the fistula ward. An unmistakable odorâlike that of a long-neglected urinalâwafts out into the open-air corridor.

ward. Dr. Roger, a slender man in a white doctor's coat who carries himself with a quiet elegance, has led us through Panzi's outdoor walkways and neatly cut lawns, past the “bad fed” (malnourished) children, the rows of male patients with bandaged gunshot wounds, the maternity and C-section wards, and finally, here, to the fistula ward. An unmistakable odorâlike that of a long-neglected urinalâwafts out into the open-air corridor.

The air here is weighty, like the wailing that filled the parking lot when Serge shut off the engine. I spotted a girl in the corner, doubled over, crying out some Swahili lamentation over and over again between her sobs. I averted my eyes, watching the rain collect on the windshield, as we sat quietly listening to her cry.

Dr. Roger calls Marie over, explaining that she was gang raped when she was five years old. I try to make friends. “Marie is my sister's name.” I tell her. “Dr. Roger tells me you've been to my country.”

Marie disappears for a minute, returning with a photo book, the home-designed kind printed at Kinko's, apparently made for her by “American friends.” Someone in the United States heard about her situation and sponsored her to come to the States for treatment, accompanied by her grandmother. A church? A family? Someone in Texas? I can't tell.

I flip through the pictures of Marie in someone's suburban home, her grandmother in an American kitchen, Marie in the hospital. She stayed for months, undergoing multiple surgeries and receiving the highest standard of care as they rebuilt her insides.

A year after her return to Congo, she is back in the hospital with complications. The American operations were unsuccessful. Everyone knows why she is here. I don't ask her any more questions.

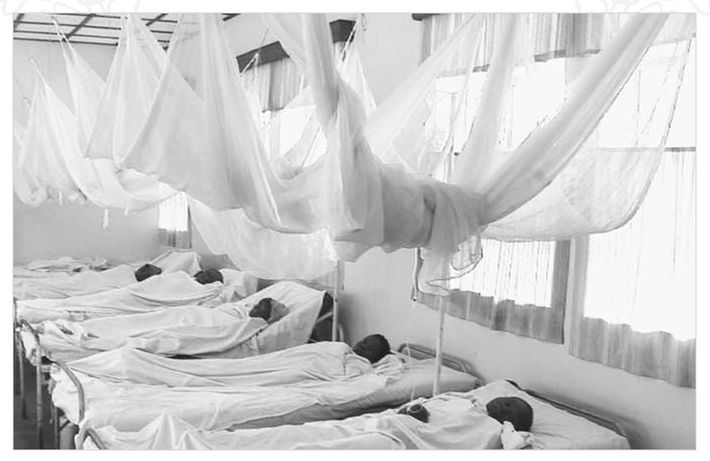

A haunting silence hangs in the fistula ward, like the gauzy netting that hovers above each patient. In the dingy yellow room with twelve basic metal hospital beds, women lie flat, shrouded in white sheets that they pull up to their chins. Only their heads peek out. They are recovering from fistula surgery and watching us with a reserved curiosity.

The nurse prompts me, “Would you like to say something to them?”

I look over at Kelly, who motions for me to take the lead. Even with hundreds of letters to my sisters behind me, now that I'm facing a room full of women who have been tortured, I feel impossibly insignificant. I scramble, trying to remember the speeches I rehearsed mentally on all of those long training runs.

There is no choice but to stumble through whatever bits and pieces come to mind. I tell them about what we've done through Run for Congo Women, trying to get to resilience and beauty and inspiration, the part about them being my heroes. “All of you . . .”

I can't. I am at a loss. Blank.

And worse, I choke. I start to cry.

I have their attention now. They sit up, watching me keenly.

I can't say anything else.

The nurse says something to them.

I ask the translator what the nurse just said.

“The nurse told them, âShe feels very sorry for you.'”

Not heroes. Not beauty. Not resilience. Pity. The opposite of what I wanted to say.

The nurse coaxes them into a weak round of applause.

Should I take a bow?

Should I take a bow?

I vow that I will not cry in Congo again.

We are ushered into the open warehouse space that serves as the hospital activity center, where hundreds of women are crammed along the tables like sardines. They form a beautiful mosaic of headscarves and colorful dresses, yet it feels like a holding pen on a factory farm. I recognize it from Lisa Jackson's film, in the scene where she asked, “They were all raped?” Her guide responded, “All of them.”

The nurse explains the program. “Each day, they start with prayer and Christian songs. Then they are taught literacy and numeracy and different skills.” She holds up plastic bags and mats the women weave in fluorescent yellow,

pink, and orange. “They sell them. They sew as well. Before they had any activities, they were very, very sad. Many psychological problems. You would find them sitting off to the side, just weeping. But when they are doing this activity, they seem to be very happyâvery pleased.”

pink, and orange. “They sell them. They sew as well. Before they had any activities, they were very, very sad. Many psychological problems. You would find them sitting off to the side, just weeping. But when they are doing this activity, they seem to be very happyâvery pleased.”

I stare at the viewfinder on the camera, watching them. Journalists have made a habit of filing in and paying their respects here at this warehouse. Somewhere in the back of my mind, I hear my friend Anne's warning: “So many journalists show up in Congo saying, âShow me the raped women!' Be human about it. Be a woman about it.”

They know they are being studied. I wonder if they have agreed to be filmed, and how often they are asked. Do they feel herded, transparent, with their deepest humiliation on broad display, simply by virtue of sitting in this warehouse? I scan their eyes. They look indignant, numb, suspicious, exhausted, angry, bored, defensive . . . but

pleased?

I don't see it.

pleased?

I don't see it.

I want to prep my speech this time. I want to get it right. I turn to Maurice and ask, “Can we work on this âheroes' thing?”

“Yes, hero . . .”

“Like someone you look up to. Do you understand? Someone you admire.”

I'm not sure they get it.

I turn to Kelly, “I feel embarrassed to make a speech, but they've been waiting a long time. It's expected. You should talk too.” Yet Kelly stands back, as though an unspoken rule was made a long time ago, maybe in D.C.: I'm the one who does the talking.

“Okay!” I turn to the crowd, puffing myself up with a strained cheeriness. I almost flinch at how much I sound like a cheerleader, one who is calling her troops to attention. I try to gauge the crowd. Some are focused on weaving plastic baskets; others are looking at me skeptically. “I'm happy to be here to visit Panzi Hospital. Thank you for waiting for us.”

The gregarious nurse, clearly used to rallying the troops, knows the right toneâthe “how-you-talk-to-rape-victims” tone. Maurice translates English to Swahili, and the nurse adds the extra filter, a safety net.

“In the U.S., I learned about Congo when I was watching television one day, and my life changed . . .”

As it's filtered through two translators, I scan the crowd, wondering how this is going to land. I suspect not well.

The crowd claps and I catch a few smiles. Emboldened, I speak more passionately, using broad hand gestures to minimize the language barrier. “I know you probably feel really alone here, but more and more and more American women are learning about you and they're trying to help. You aren't alone, because we care and we are doing everything we can.”

They applaud. I smile at Kelly. It's working.

“Thanks for the applause! But I want you to know Congolese women are my heroes, our heroes, because to live through what you have lived through takes so much strength and inner beauty. I can look around at every single one of you and see something beautiful that no militia can ever touch.”

They cheer!

I hold my hands up and join the clapping, pointing back at them, declaring, “We're clapping for you!”

No translation necessary! They

love

that! Erupting into applause, smiling, some even shout out,

“Ndiyo!

Yes!”

love

that! Erupting into applause, smiling, some even shout out,

“Ndiyo!

Yes!”

The translator leans over to me. “Your presence really affects them.”

As the crowd settles down, I ask them, “Is there anyone here who feels strongly about saying something to American women?”

A modest young woman with a raw aura, wearing a bulky pink sweater and headscarf, steps to the front and speaks directly to the camera.

“I do. Thank you for the two of you who came to visit this place. Please tell other American women to continue thinking about our bad situation. And that program you have for Congolese women, don't let yourself fall by the way, but continue up until the end.”

She clasps her face, trying to hide the oncoming eruption, then bursts into tears.

I put my hand on her shoulder, trying not to choke up. She keeps talking through her sobs, repeating “Mama Ah-meh-ree-kaah.”

The translator simply says, “She's crying for help from American women.”

She cries out through the tears. “We came to be cured because we were raped! But if we go back to the village, we could be raped a second time by four men, five men, six men!”

Instinct takes over and I embrace her, cradling her while she cries.

The nurse interrupts and says, “In order to get out of this psychological problem, let's sing a song to make us happy.”

The girl retreats to her place as the nurse beats the table as a drum, leading the women in a song, repeating a word even I could make out: “Amen.”

Â

A MEMBER OF THE STAFF ushers us to Marie's private room, off the fistula ward, to talk with the raw-faced girl in pink who spoke at the meeting. She is twenty-two and unmarried, soft-spoken and shy.

“How was it you came to Panzi Hospital?”

“To be cured,” she answers.

“Of what?” I ask in a tiptoe tone of voice.

“Urine.”

“How did you come to have a fistula?” I ask, as gently as possible.

“I was sleeping in my house when those negative forces came

.

They woke my parents and brothers. In a family of eight, I am the only girl. So they beat the boys and my parents.”

.

They woke my parents and brothers. In a family of eight, I am the only girl. So they beat the boys and my parents.”

She starts to cry, “Then they started having sexual intercourse with me in front of my brothers and my parents. When they finished they took metal and introduced it into my vagina, so the metal tore my vagina.”

“How long ago did that happen?”

“June 2004.”

“How long have you been at Panzi?”

Other books

The Modern Library by Colm Tóibín, Carmen Callil

Blindsided - A Stepbrother Romance Novel by Kylie Walker

Twist Me by Zaires, Anna

Deep Surrendering (Episode Three) by Chelsea M. Cameron

One in 300 by J. T. McIntosh

Dying to Score by Cindy Gerard

Seduced by the Night by Robin T. Popp

Fade to Blue by Bill Moody

Caged in Darkness by J. D. Stroube

Midnight in Montmartre: A French Kiss Sweet Romance by Chloe Emile