A Thousand Sisters (26 page)

Read A Thousand Sisters Online

Authors: Lisa Shannon

Later, I will look up the poem.

YOU AND I ARE DISAPPEARING

The cry I bring down from the hills

belongs to a girl still burning

inside my head. At daybreak

belongs to a girl still burning

inside my head. At daybreak

Â

she burns like a piece of paper.

Â

She burns like foxfire

in a thigh-shaped valley.

A skirt of flames

dances around her

at dusk.

in a thigh-shaped valley.

A skirt of flames

dances around her

at dusk.

Â

We stand with our hands

Â

hanging at our sides,

while she burns

while she burns

Â

like a sack of dry ice.

Â

She burns like oil on water.

She burns like a cattail torch

dipped in gasoline.

She glows like the fat tip

of a banker's cigar,

She burns like a cattail torch

dipped in gasoline.

She glows like the fat tip

of a banker's cigar,

Â

silent as quicksilver.

Â

A tiger under a rainbow

at nightfall.

She burns like a shot glass of vodka.

She burns like a field of poppies

at the edge of a rain forest.

She rises like dragonsmoke

to my nostrils.

She burns like a burning bush

driven by a godawful wind.

at nightfall.

She burns like a shot glass of vodka.

She burns like a field of poppies

at the edge of a rain forest.

She rises like dragonsmoke

to my nostrils.

She burns like a burning bush

driven by a godawful wind.

IN THE MIDDLE OF the African night, I am haunted by the title.

You and I Are Disappearing

. When I was fourteen, I hadn't a clue how the title related to a poem about a girl burning in a napalm attack. During the Q&A period following Komunyakaa's reading, I asked him, “Who are the âyou' and âI' and how are we disappearing?”

You and I Are Disappearing

. When I was fourteen, I hadn't a clue how the title related to a poem about a girl burning in a napalm attack. During the Q&A period following Komunyakaa's reading, I asked him, “Who are the âyou' and âI' and how are we disappearing?”

Who are the âyou' and âI'? How are we disappearing?

I understand his answer now. I crawl out of bed and scrawl it down in my notebook. I know exactly who the “you” and “I” are. The burning girl is almost every person I've met in Congo, and me, or us, when we watch the Congolese burn “with our hands at our sides.”

We wake up and stroll down to the sea. In the daylight, the whole resort is like a giant set for a stock photo shoot, no retouching required.

The day unfolds in a slow-motion haze. An elaborate breakfast buffet,

a swim, iced tea on the jetty, massages at the hotel spa, a visit to a fishing village overrun with backpackers, a long nap. The resort is nearly empty. In the quiet moments, I occupy myself by mentally sketching a shoot hereâcasting, storyboarding, forming shot lists, framing shots. Otherwise, I continue to barrage D with intrusive personal questions. Nothing if not gracious, D obliges them all. I will do anything to keep the focus off me, off Congo, off cracking.

a swim, iced tea on the jetty, massages at the hotel spa, a visit to a fishing village overrun with backpackers, a long nap. The resort is nearly empty. In the quiet moments, I occupy myself by mentally sketching a shoot hereâcasting, storyboarding, forming shot lists, framing shots. Otherwise, I continue to barrage D with intrusive personal questions. Nothing if not gracious, D obliges them all. I will do anything to keep the focus off me, off Congo, off cracking.

Alone at the resort's bar perched above the sea on a jetty, we gaze out over the ocean. I realize it's the first time I've looked at the night sky over Africa. D points out constellations he remembers from his childhood in South Africa. They're playing one of the Buddha Bar albums in the background, one we both own. Each of us loved it at first, we discover through conversation, then grew bored with it. It's just us and the bartender, who remains remote. I say, “I imagine you live in a place like this, modern, clean.”

“Nope. I've lived in the same Victorian townhouse for the past twenty years, since I left academia.”

I'm impressed. To build a global software empire and not upgrade your house? To use all of your resourcesâmoney, time, and influenceânot for a better lifestyle, but to save the planet? Those are values.

We fall into a deep conversation about wealth as the great divider. We talk about two kinds of philanthropists: those who write big checks and those who doggedly work for something bigger than themselves. He tells me about acquaintances who fuss and send back a glass of water if it has four ice cubes instead of three. I tell him about my grandfather's work with Dominique and John de Menil founding the Rothko Chapel in Houston, an interfaith place of worship dedicated to human rights. Family legend had it Dominique de Menil, aka “Mrs. D,” insisted on riding public transportation until she was in her eighties, when her staff finally had to talk her down: “You're

eighty

. It's okay to take a car!” Or the Vogels, who I saw on a segment of

60 Minutes

I watched with my Dad many years ago. They built an art collection worth hundreds of millions of dollars, yet still live in the

simple two-bedroom apartment they bought when Mr. Vogel worked for the postal service. I comment, “Artists love them because they're in it for art, and notâ”

eighty

. It's okay to take a car!” Or the Vogels, who I saw on a segment of

60 Minutes

I watched with my Dad many years ago. They built an art collection worth hundreds of millions of dollars, yet still live in the

simple two-bedroom apartment they bought when Mr. Vogel worked for the postal service. I comment, “Artists love them because they're in it for art, and notâ”

“The commerce of art,” D says, finishing my sentence.

“Exactly.”

The more we talk, the more I realize he doesn't quite fit into the Big Important Guy demographic. He likes to secretly meditate in the woods, craves all things simple, and writes in his spare moments, scrawling down poetry to zone-out in board meetings. He's undeniably intense. Of all things, lurking under his thick persona is a quirky-pensive-brilliant artist. As we do that odd dance between foreigner and friend, I wonder if I might be sitting next to someone I will know outside of Africa.

We return to the room and, snuggled next to D, I sleep for the first time in days.

In the morning, we walk across a vast, pristine beach, arms stuffed with snorkeling gear. There's nothing commercial here, just African women in pastel dresses wading waist-deep in the ocean with fishing nets trailing behind them. D turns to me and says, “You could shoot here!”

“Too much seaweed on the beach,” I blurt out, regurgitating Ted's predictable objection.

Did I just tell an environmentalist that Nature isn't good enough?

“The dark side of Lisa,” D says, raising his eyebrows, “Part two.”

There is nothing complicated about fish. They are beautiful, simple little beings in weird, wild shapes and neon colors, like eighties cruise-ship clichés, some with frills that remind me of war-era secretaries in black-and-white polka-dotted dresses. I squeal with delight, smiling so wide I break the seal on my mask. It floods with water over and over again, so I have to keep coming up for air.

We get back late, in a rush to make it to the airport. While the taxi driver loads my bags, D and I pause for a moment. We're too rushed for a decent goodbye, and I'm too worn down to drum up some witty, sexy, romantic endnote.

“I can't believe you're going back to that place,” he says, kissing me goodbye.

I ignore the slow-creeping adrenaline buzz that comes when I think of Bukavu's gutted streets. My inner college-era feminist is tickled by the role reversal: powerful man kisses young woman goodbye on

her

way back to a war zone. He adds, “Don't do anything I wouldn't do.”

her

way back to a war zone. He adds, “Don't do anything I wouldn't do.”

Yeah, right.

I laugh, and say teasingly as I climb into the taxi-van, “I'm already doing something you wouldn't do.”

I laugh, and say teasingly as I climb into the taxi-van, “I'm already doing something you wouldn't do.”

As the taxi pulls away, D stands in the driveway of the hotel watching me. I look down at my arms, which are getting redder by the minute. I press my fingers down and fixate on the white imprint that remains. My back smolders with my only Zanzibar souvenir: the worst sunburn I've ever had. It will blister and peel for the remainder of my time in Africa, aggravated by the daily thrashing from bumping over Congo's washed-out roads. Two years from now, the faint traces of the swimsuit I picked up in the hotel gift shop will still be burned onto my back.

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

Goodbye Party

THE WOMEN FOR WOMEN

staff is abuzz with the imminent arrival of the organization's founder, Zainab Salbi, and the writer Alice Walker.

staff is abuzz with the imminent arrival of the organization's founder, Zainab Salbi, and the writer Alice Walker.

Hortense called early this morning, letting me know in no uncertain terms that I am not invited to their arrival reception or to any of their meetings with women, including Generose. I don't know why and I won't lie: I'm disappointed. Especially after days of enthusiastically trying to walk the Congolese staff through every Alice Walker work I've readâfrom

Meridian

to

Possessing the Secret of Joy

âtrying to remember all the key points I made in a twenty-five-page college paper comparing

Their Eyes Were Watching God

and

The Color Purple

. But as anyone who has engaged in the political minefield that is celebrity wrangling can tell you, this kind of thing goes with the territory. I decide to not take it personally and make plans to spend my day-in-exile following up with some of my new Congolese friends.

Meridian

to

Possessing the Secret of Joy

âtrying to remember all the key points I made in a twenty-five-page college paper comparing

Their Eyes Were Watching God

and

The Color Purple

. But as anyone who has engaged in the political minefield that is celebrity wrangling can tell you, this kind of thing goes with the territory. I decide to not take it personally and make plans to spend my day-in-exile following up with some of my new Congolese friends.

First up, Generose. Her brother has collected her children from various friends and neighbors, so they are now fine. It's time to break the news about the house. I sit next to her on her hospital bed. I don't want any of the other sisters in the neighborhood to be jealous, so I've made up a story.

“I've found an organization that provides small grants for people who are disabled because of war-related injuries,” I tell her. “They are going to build you a small house.”

“I've found an organization that provides small grants for people who are disabled because of war-related injuries,” I tell her. “They are going to build you a small house.”

For a moment, she sits quietly, absorbing the news. Then she lifts her hands up and cries out, “

Aksanti sana sana sana! Merci!”

Thank you very, very, very much.

Aksanti sana sana sana! Merci!”

Thank you very, very, very much.

On the way out, we stop by the baby ward to check on Bonjour. As I take him in my lap, shouting fills the room. We all watch, stonefaced, as a man yells at a crying child in the corner. The man moves on to the next bed, lays his hands on his next victim and launches into his routine once again, apparently egged on by the fact that the whole ward is staring at him. The new baby screams with fear while the man holds his hands above the child in some form of prayer symbol. Ah, he's exorcising demons.

I focus on Bonjour, touching his tiny fingers, looking in his eyes, trying to block out the Congolese exorcist. The little guy is getting better. His skin is darker and the half-light in his eyes is gone. He smiles.

I get up to leave. As I'm heading for the door, his mom asks, “What about sugar for my tea?”

I stop cold and look back at her, fed up with the

muzungu

routine. “You can live without sugar.” Without waiting for the translation, I leave and don't look back.

muzungu

routine. “You can live without sugar.” Without waiting for the translation, I leave and don't look back.

Â

HORTENSE CALLS. Zainab, Alice, and Christine will arrive at any time. The staff has cleared the compound completely, but my first group of sisters

(“Money! More money!”)

showed up three hours ago hoping for one last goodbye celebration. They refuse to leave.

(“Money! More money!”)

showed up three hours ago hoping for one last goodbye celebration. They refuse to leave.

We beeline it over there, load the women and babies ten at a time into the SUV, and take them to the vocation skills center down the road in the last harried minutes. On the main road, we pass the Women for Women SUV carrying Zainab and Alice.

At the skills center, we settle in and relax, drinking sodas. I notice I'm

sitting across from little Lisa, so I greet her. The sister next to her holds a baby as well, her hair braided with pink ties and barrettes. “Her name is Lisa too,” the mother says. Two little Lisas! I wonder how many Congolese babies are out there sporting American names like Ashley and Deborah because their mom was sponsored when she was pregnant.

sitting across from little Lisa, so I greet her. The sister next to her holds a baby as well, her hair braided with pink ties and barrettes. “Her name is Lisa too,” the mother says. Two little Lisas! I wonder how many Congolese babies are out there sporting American names like Ashley and Deborah because their mom was sponsored when she was pregnant.

Another sister presents me with her newborn. “I told you, if I deliver the baby while you are here, you will name the baby.”

I've never had plans for children, so baby names have never been on my mind. I draw a complete blank. I stall. “Can I hold him?”

She hands him to me, wrapped in blankets. Yep, he looks brand-spanking-new, his face still pale and wrinkly. I ask her, “What do you hope he will be like?”

“Strong, responsible, someone who supports the family.”

No pressure there. I stare at the little guy, at a loss. Strong, responsible . . . a lightbulb goes on. “I have an idea, but it's not going to sound like a Congolese name,” I say. They all laugh.

“My father was strong and responsible.”

They burst into applause, saying “Yes!” and “Amen!”

“My father's name was S-T-E-W-A-R-T. Stewart.”

They look puzzled. They all try to rehearse it. It does not roll off the Swahili-speaking tongue. “Stu-ad. Stu-at.”

The new mom tries to write it on her hand, but I jump in. “I'll write it.”

I hand the baby back. They cheer, laughing, as I write STEWART in block letters on Mom's palm. She looks skeptical. “He was a loving, compassionate man,” I tell her. “He worked with people to heal their war trauma.”

“Yes.”

“Are you going to change the name?” I ask, hoping my smile gives her visible permission to name her baby anything she pleases.

“I will keep the name.”

They present me with a carefully wrapped gift. One woman, standing at my side, says, “We have nothing to give you as a present. But what we can do

is thank and thank and thank you for what you did for us. May God bless you and increase your power to give and to give and to give and to give.”

is thank and thank and thank you for what you did for us. May God bless you and increase your power to give and to give and to give and to give.”

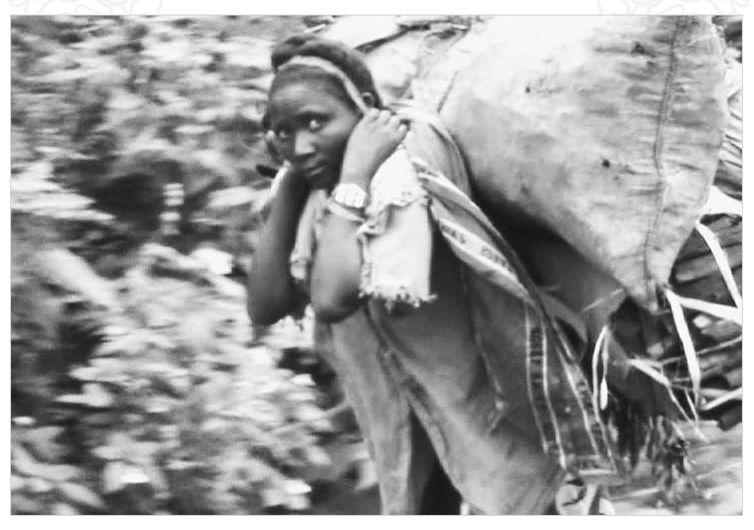

They present me with a woodcarving, a sculpture of a woman with a baby strapped to her back. One woman interprets it for me. “This is your image as Mama Congo. We are like your babies.”

Other books

Chronic City by Jonathan Lethem

The Prudence of the Flesh by Ralph McInerny

Hunger of the Heart (Wolves of Ravenwillow Book 1) by Magenta Phoenix

The navigator by Eoin McNamee

To Love and Trust (Boundaries) by Swann, Katy

Mecanoscrito del segundo origen by Manuel de Pedrolo

Mr. Red Riding Hoode: Poconos Pack, Book 2 by Dana Marie Bell

Deadly Night by Heather Graham

Seaglass Summer by Anjali Banerjee

The Velveteen Rabbit & Other Stories by Margery Williams