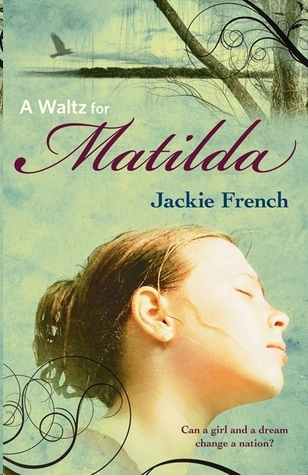

A Waltz for Matilda

Read A Waltz for Matilda Online

Authors: Jackie French

To the seven generations of women who taught me the

lessons in this book

A love song to a land, and to a nation

Apology

This book is set from 1894 to 1915, a time of widespread racism, some of it quite unconscious. The desire to pass new comprehensive laws to ‘keep Australia white’ was one of the reasons many supported the federation of states that became the nation of Australia. Writing about those times has needed racist words and racist assumptions that are not — and should not be — in common use today. But without them it would be impossible to show the hatred of those times or the ideas that made today’s Australia.

Jackie French

AUGUST 1894

Dear Dad,

I hope you are well.

Did you get my last letter? Mum and I are not at Aunt Ann’s now, we are living with Mrs Dawkins in Grinder’s Alley. It is a boarding house, we only have one room but Mrs Dawkins is kind, she found me a job. It is in a jam factory. I pretend I am fourteen not twelve so I get paid three shillings a week. The boys get six shillings, which is not fair.

A bullock dray fell on Aunt Ann. She did not get better. Mum and I could not pay the rent. The bailiffs came and took our furniture. Mum had to go to hospital for an operation, but we do not have the money for doctors now. Mum is very thin and cannot do her sewing, but she says she will be better soon.

I hope you are all right. We have not had a postal order from you for more than a year, that is why I wonder if you got my letters, and know what happened to Mum and Aunt Ann.

It is very different in Grinder’s Alley from Aunt Ann’s, all the houses are squashed together. The smoke from the chimneys just sits above the houses. Our rent is a shilling a week, I buy day-old bread and spoiled vegetables to make soup and Mrs Dawkins lets me use her kitchen, but there is not enough money to buy medicines, so I hope you will send a postal order soon.

I miss Aunt Ann and my friends at school. It is too far away for me to see them; also I have only Sunday off each week. I am worried about Mum too. She says she is all right but I do not think she is.

Give my love to the sheep and the lambs, I wish I could see them and your farm some day, and you too.

Do you have a dog? I like dogs.

Your loving daughter,

Matilda

PS It is hard for Mum to breathe in Grinder’s Alley. If we could come to the farm I think she might be better.

PPS If somebody else is reading this because Dad is away shearing could you send it to him please, I think maybe he does not know where we are now, or that Aunt Ann died.

It was midnight in Grinder’s Alley. The gas lamps flickered in the darkness. Somewhere in those shadows lurked the larrikins of the Push, with their hot breath and cold knives.

Matilda put her chin out. The jam factory was only three streets away from Mrs Dawkins’s. She’d managed to escape the Push before. She’d make it tonight too.

She clutched her shawl closer as she slipped down the boarding-house steps. Since the bailiffs took their alarm clock, she didn’t dare sleep all night with Mum. There were too many women with hungry children who’d take her job if she was late.

The houses crouched like mushrooms behind their iron railings. Matilda ran as fast as her skirts would let her, staying close to the fences, one shadow among many. The night air smelled of smoke from coal fires, and the big furnaces of the jam and tin factories. Someone was cooking sausages too. Her tummy clenched into a knot.

She’d eaten nothing since Tommy’s sandwiches yesterday. She’d told Mum the factory gave the workers dinner. It was a lie: Mr Thrattle’s cockroaches ate better than his workers. But Mum was so thin these days. Two shillings a week only bought food for one.

Why hadn’t Dad sent money? Shearers had to go places without post offices, but he’d always managed to get money to them every few months.

A shadow moved in the dimness further up the alley. She stepped back into a shop doorway, then relaxed, as Ah Ching emerged from the darkness, pulling his vegetable cart.

Aunt Ann had said that Chinese men wanted to kidnap white girls and sell them into slavery. Impossible to think of Ah Ching doing that.

Mrs Dawkins said that when the Push had tried to steal Ah Ching’s vegetable cart, Ah Ching had moved like the wind, chopping, leaping, a knife of his own suddenly in his hand. Impossible to think of this small gentle man leaping with a knife too.

But the Push never troubled Ah Ching now.

Matilda watched the small, grey-headed man pulling the handles of the big cart, piled high with tight green cabbages, bunches of carrots, beetroot, leeks and wooden cases of fruit, each piece wrapped in newspaper to stop it bruising. Ah Ching’s wrinkles changed into a smile when he saw her.

She bowed her head and right knee slightly, then looked down. ‘Qing An.’

Ah Ching had taught her the words and how to bow properly weeks ago, when they first met. She had no idea what the words meant. But Ah Ching’s smile deepened when she bowed and spoke.

‘Qing An.’ He bowed back — a lower bow than hers — then reached into his cart. His hand brought out a crumple of newspaper. He bowed again as he handed it to her.

Matilda unwrapped it carefully. A peach! Even by the lamplight she could see its blushed white skin, like Mum’s cheeks. She lifted it and smelled its sweetness.

‘Duo xie!’ She bowed again, wishing she knew more Chinese words to thank him properly, then slipped the peach into her bag.

Ah Ching waved his hands. He said something she couldn’t understand, then made chewing motions. He meant that she should eat it now.

How could she explain how badly Mum needed fruit like this, if she was to get well? She hesitated.

Ah Ching’s smile changed: became deeper, gentler, rich in understanding. He picked out a second peach, then held it out to her, bowing.

She looked at him, speechless, then unwrapped it slowly, letting the smell seep into her nose. The first bite was like slipping into the waves at the beach or clean white sheets. The juice exploded down her chin. She wiped it, embarrassed.

Ah Ching laughed softly, as though delighted at the compliment to his peach. He watched her steadily as she ate it all, using her nails to gouge out the last peach strings from the seed.

Matilda bowed again. ‘Gai ri zai lai, qing zou hao.’ They were the only other Chinese words she knew.

Ah Ching nodded. For a moment she thought he would say something more. But instead he simply bowed, and began to trot toward the market.

Or maybe he’s going to sell his fruit and vegetables from house to house, thought Matilda, listening to the creak of the wheels fade out down the cobbles as she turned alone into the next shadowed street. She and Ah Ching knew nothing of each other, except this brief friendship of the night, linked by fruit and darkness.

‘Got her!’ A fist reached out of the darkness and grabbed her by her collar. Another boy’s hand seized her arms. Snagger Sam carried a bag of pennies, dangling from one hand. Mrs Dawkins said he’d blinded a cove with those. Todger Bailey held a knife. She didn’t know the names of the others, short-coated bullies with lengths of lead pipe or knotted cord and beery grins.

Aunt Ann said drinking spirituous liquor drove men mad. Matilda gazed from one boy to another.

No point struggling. No point screaming either. No one answered screams round here. The Push carried matches and cans of kerosene. If you crossed the Push you’d find your house burned down, and with you in it if you didn’t get out in time.

‘Out late again, little girl?’ Todger Bailey stuck his knife up to her throat. ‘You know what happens to little girls who go out in the dark?’

Snagger Sam laughed. ‘They learn to do what they’re told. Ain’t that right, boys?’

‘You gunna do what we tells you?’ whispered Todger’s beery breath in her ear. ‘You gunna be nice, little girl?’

She couldn’t let fear take her now. She had to get to the factory — and she couldn’t if she’d been taken by the Push. But Tommy had told her what to do. Tommy knew everything. Or she hoped he did.

She let her body go limp.