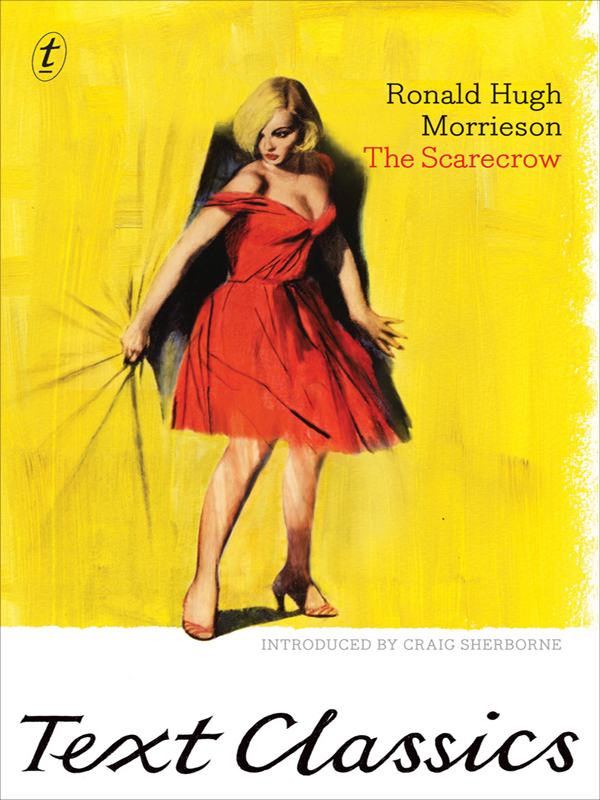

The Scarecrow

Born in 1922, RONALD HUGH MORRIESON lived his entire life in the house his grandfather built in Hawera, a small town on New Zealand’s North Island.

Morrieson’s father died when he was six, leaving his mother to raise him. A sickly child, Morrieson nonetheless developed a passion for gangster movies, jazz and touring cars. He left Hawera to study law in Auckland in 1940 but lasted only a few days before he caught the train home.

He soon joined a local dance band, playing double bass. An eternal bachelor, he supplemented his income by teaching music and with a range a different jobs including barman, billiard maker, borer-eradicator salesman, brush hand, truck driver and hotel cook.

The Scarecrow

was published in 1963, and was followed a year later by

Came a Hot Friday.

After a subsequent novel was rejected Morrieson’s health declined; his condition was exacerbated by depression and grief at his mother’s death in 1968.

Plagued by heart problems and cirrhosis of the liver, he became a recluse and died on Boxing Day in 1972.

CRAIG SHERBORNE is the author of two acclaimed memoirs, a novel,

The Amateur Science of Love

, two volumes of poetry and a verse drama. His journalism and poetry have appeared in Australia’s leading literary journals and anthologies.

ALSO BY RONALD HUGH MORRIESON

Came a Hot Friday

Predicament

Pallet on the Floor

Proudly supported by Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

Copyright © Ronald Hugh Morrieson 1963

Introduction copyright © Craig Sherborne 2012

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published by Angus & Robertson 1963

First published by The Text Publishing Company 2002

This edition published 2012

Designed by WH Chong

Typeset by J&M Typesetting

Primary print ISBN: 9781921922398

Ebook ISBN: 9781921921971

Author: Morrieson, Ronald Hugh, 1922-1972.

Title: The scarecrow / by R.H Morrieson ; introduction by Craig Sherborne.

Edition: 1st ed.

Series: Text classics.

Other Authors/Contributors: Sherborne, Craig, 1962-

Dewey Number: NZ823.2

by Craig Sherborne

THE definition of joy is sex and alcohol. Put together they’re likely to land you in sweet strife. If you’re in Ronald Hugh Morrieson’s great comic-thriller-horror novel

The Scarecrow

they certainly will. If you’re one of his adult male characters you’ll drink till you’re garrulous and boastful, then fall asleep. Sex will be more wishful thinking than the act itself. You’ll have smutty intentions but be all talk. Though watch out for creepy old codgers with predation stirring their loins. They’ll ply young girls with grog so they can feel them up. The creepiest has a penchant for killing his victims and raping them in the necrophilic fashion. If you’re an adolescent Morrieson will portray you as clumsily experimental with sex, as is the natural order. Hetero boys will masturbate each other in lieu of having a girl-friend. The town’s

man’s sports car and let the liquor fetch her along till she feels curious enough to let the bloke do what he will. Her ageing employer even gets a go, allowed to undo her blouse.

All the while Morrieson exercises his tone-perfect gift for mixing sinister narratives into the lives of main characters who are half-decent and well-intentioned. Take the legendary opening line: ‘The same week our fowls were stolen, Daphne Moran had her throat cut.’ It is a masterful melding of opposite ideas. That such a sophisticated literary trick should be performed by the ‘big dunce’ narrator of the novel, Neddy Poindexter, would beggar belief but Morrieson solves that by having Neddy inform us he appropriated the idea from

Treasure Island

. He’s trying to set out a ‘genuine blow-by-blow account’ of a series of shocking events that took place in his town when he was fourteen. ‘Grant me a little licence,’ Neddy asks of his readers.

We do. You read this book smiling and laughing, regardless of the horrors in it. Neddy’s conscientious voice warms us up like a bottle of good brandy. Off we go with him through the insular and sleazy, contented and malcontented, intellectually and financially impoverished community of Klynham, a facsimile of Hawera, the small town in New Zealand’s North Island where Morrieson lived all his life. The backyards littered with junk, the lonely back lanes, the shabby main-street pubs. The delinquents, the halfwits, the

Salvation Army brass band. The petty class hierarchy. The unwanted pregnancies. No matter how weird the story and characters, the setting has a documentary realism. And as it romps along you hardly have time to savour the Joe Orton-style deadpan sarcasm that gives the plentiful humour bite.

Ask a country person anywhere what they get up to in their spare time and they’ll probably answer, ‘We make our own fun.’ It’s a bucolic mantra. Which is where sex and alcohol come in. Neddy may be naive but he’s not stupid, nor entirely innocent, lusting after his own sister in that secret way some siblings do. He can look on horrible events and be shaken but too transfixed to avert his eyes. It testifies to Morrieson’s talent for balancing credibility with farce that we trust his young narrator to relay sordid matters of the flesh so eloquently. Not to mention Neddy’s weakness for a bit of poetry: ‘The moon was in the gutter of the sky with its parking lights on.’ Or, ‘It was hard to believe that the wriggling witch-doctor on the seldom-drawn blind was only the shadow of our old karaka tree.’

Like most of the men in

The Scarecrow

Morrieson was a feckless type, a drunk, a lecher, a charming raconteur who played in a local jazz band but had no career to speak of. He lived with his mum, wrote four novels,

The Scarecrow

(published by Angus &

Robertson in 1963) being his first and most celebrated. He died young—aged fifty, in 1972, after a drinking binge. His best mate was the local undertaker. If the real-life undertaker was anything like Charlie Dabney, the incompetent, permanently pissed undertaker in this novel, you wouldn’t want to have died in Hawera.

In

The Scarecrow

Dabney and his drinking buddies befriend an itinerant fellow, Hubert Salter. He is a repellently ugly individual but has grandiloquent manners and a flattering turn of phrase that appeal to the citizens and their silly pretensions. He is also a professional magician and mind reader: Salter the Sensational. What they don’t know is that he is on the run, having killed and desecrated Daphne Moran in another town. And his deviant urges have not been sated. He wants another victim.

This is how Neddy, in one of his ‘little licence’ moments, alerts us to these vile intentions: ‘“The wolf bane is blooming again,” Salter muttered. The high-light of his life over the last few days suddenly flashed back to numb his brain. Ecstasy flooded his loins and his genitals.’ Then, ‘So easy it had been. So almost unbelievably exciting. Such mad exhilaration, such sexual power the mad, evil moment granted. So easy it must always be.’

It’s common for people encountering Morrieson’s books for the first time, especially

The Scarecrow

, to say something like, ‘He is

out there

.’ Or, ‘That’s trippy.’ Or, ‘That’s really bizarre.’ I guess it depends to what degree you’ve led a sheltered life. You might think, in an age of simulated autopsies on prime-time TV, blood-splattering violence and bare-arsed coitus, that Morrieson’s efforts would hardly seem out there. He knows when to shut a scene down and let the reader’s imagination do the rest of the work. That’s what makes him so spooky. Explicitness keeps the reader at a safe distance from confronting material. It doesn’t seek access to our imagination the way Morrieson’s suggestiveness does. Normality and aberration sleep in the same room in our imagination, and one sometimes climbs into the other’s bed. A novel like

The Scarecrow

takes us into that room within ourselves.

‘Original’ is another adjective that gets a run—an almost derisive term these days, when so much of literature, like much of life, is formulaic, compartmentalised, predictable. Novels are

meant

to be original! They are not supposed to conform to received taste, a hand-me-down set of cultural orthodoxies. And I pray

The Scarecrow

will be spared the lazy contemporary habit of consigning books in which bad things happen to the dump bin of ‘exploring the dark side of human nature’.

Not that Morrieson would have cared where he

was consigned. Towards the end of his life, when he’d been sucked down into reclusive alcoholism, he thought his writing would die with him. He reportedly said, ‘I hope I’m not going to be one of those poor buggers who gets discovered when they’re dead.’

He was.

The same week our fowls were stolen, Daphne Moran had her throat cut.

Big dunce that I was at school, my essays, if not my spelling, used to be thought quite good, and I was a keen reader, which is probably why I now presume to set myself up as the chronicler of Klynham’s hour in the limelight. This was certainly the most hectic and the darkest chapter in the whole history of the town and, just like I have heard said ‘Murder will out’, it seems to me that the true story is bursting to be told sooner or later. It may be that I am biting off more than I can chew in tackling the job, but who, I ask myself, is going to come to light if I do not accept the challenge? Who was more constantly mixed up in every scene than little me? But nobody! And whose family knew more of any ins and outs that I may have missed myself than my own family? Echo answers whose!

So it looks like it is over to me to go ahead and, in retrospect, piece together the entire grisly and dramatic episode. Nearly all should turn out to be a genuine blow-by-blow account. Some of it will have been told to me, of course, and some extra elusive bits and pieces may force me to use my imagination; but surely I get some licence if I am really going to blow the top off that strange affair at last. Grant me a little licence, then, is my plea.

In

Treasure Island

I liked the sound of ‘The same broadside I lost my leg, Old Pew lost his deadlights.’ When I get around to writing myself, I decided, that is how I am going to sound. It is harder than it looks. The opening sentence of my story is as near as I can get.

The two crimes, the one so trivial and the other so diabolical, do belong to the same story, but only because a young girl took a newspaper from her aunt’s basket, and a man whose every breath was a whiff of brimstone thought he was haunted. Klynham is two hundred and fifty miles from the city. In the city the trams clanged and the newsboys shouted; the autumn dusk was ruddy with the glare of lights. In our little town a horse would clip-clop along the dead centre of the main street at noonday; at nightfall, the lights from kitchens shone out over backyards, and the street lamps which glimmered into life were few and far between. There was a street lamp outside our tumbledown house and the moths it attracted looked as big as bats.

The name is Poindexter. It is a rather impressive name, I have always thought, and yet we were just about the most no-account outfit in the town. This is the voice of Edward Clifton (Neddy) of the Poindexter ilk and I should know.

The trouble with the Poindexters was ready cash and Athol Cudby. We had no ready cash to speak of, but we had stacks of

Athol Claude Cudby. It has long been my contention that the constant presence of that man had a more degrading influence on our household than any other factor.

Apparently, while the slump was playing fortissimo and I was playing cowboys and Indians, we became locally celebrated for not paying the rent, chopping up partitions for fuel against the wintry blasts, boozy parties, and the girls getting into the time-honoured spot of bother. Both Winifred and Constance got married the bumpy way and these things take living down in a place the size of Klynham. We also had quarrels. We lived in a whole series of houses and every one of them had a window, or windows, with a large star in the glass because somebody ducked. The house on the corner of Smythe and Winchester streets, which is where we were living in the early autumn of this memorable, nay, unforgettable, year, featured two such windows. However, by this time, things were brightening a little. We had a good-natured, easy-going landlord, and money was not playing quite so hard to get. There was even some talk of taking the owner up on his offer, paying a higher rent and making the old shack our own. Things were looking up, but we still had Uncle Athol.

Uncle Athol is a bludger, a prize bludger, the soft voiced, ‘thank-yuh-kindly’, hat-touching type whose answer to flood, famine and plague is a mackintosh. If Athol C. Cudby ever whipped up a bead of honest sweat in his whole life I would appreciate finding out just where and when in order to send it to Ripley. It is not a bit of use telling me it was losing an eye that soured him against toil, because he had both his eyes right up to the time when, strictly from hunger, he undertook to go on a fencing contract somewhere in the back of beyond, with two

cronies. First time up he took a blind swipe at a post with a hammer; and a piece of No. 8 fencing wire promptly took a swipe back and scored a Lord Nelson. On the strength of his glass eye (whoever matched that fishy eye was a craftsman and is almost certainly still whistling for the price) Uncle Athol has been known to attend an Anzac Day parade wearing an army overcoat he got from ‘Clem’s Wardrobe’, an establishment now liquidated on account of greater universal prosperity. Consider a man, who has never been closer to the army than a secondhand overcoat, attending a sacred ceremony like an Anzac Day parade just for the booze he can get out of it. This will serve to illustrate his attitude and lack of principle. ‘Bull’s wool rules the world’ is his motto and sometimes I am inclined to think he could be right. He certainly seems to have pulled the wool over a lot of eyes in this town in his time. When I was just a kid he had me bluffed too, but those days are gone.

Uncle Athol took a great interest in the hen-coop Leslie Wilson and I built when we got bitten by the poultry bug. Les was a great buddy of mine in those days when we were in short pants. We went collecting cones from pine plantations weekend after weekend, tore our pants on barbed-wire fences, fell in creeks and fell out of trees and braved all manner of hazards, including being bitten by dogs, when we hawked the pine-cones from door to door, and all to buy half a dozen Black Orpington fowls, which the auctioneer said were pullets. Looking back with a certain sourness, it is my contention that the auctioneer used the term ‘pullets’ the way a drunk would yell out ‘Hi girls’ to a busload of grandmothers on a conducted tour; but, be that as it may, those chooks belonged to Les and me and when we found a brown egg in the coop which Uncle Athol had given us

advice on how to build, to say we were walking on air is to be guilty of withholding the true facts. Saturday morning Les turned up with a book on poultry farming and now it did not seem as if anything was going to prevent us making a fortune.

‘There sure musta been fowls around for some time,’ I said, looking through the book, which had no cover and seemed to be written in copperplate on parchment. At a glance it might have been a first edition Chaucer. ‘’Stonishin’ to think of ‘em having fowls way back when like this.’

‘Don’tcha worry yuh head over that,’ said Les, reclaiming the book. ‘There weren’t too many flies on these oldtimers. This old geezer here with the beard musta known fowls like the palm of his hand to write this book. Way I look at it, with a book like this to refer to and study, we’d just be wasting our time going on to the Tec. With a book like this and the super strain of fowls like we managed to get for a kick off, there just isn’t any point in wasting our energy on anything else. We’ll be able to retire and just spechlise in breeding before we’re any age at

tall

.’

‘Seems funny those chooks are still in the box at the back at this hour,’ I said, poking a stick through the wire-netting. ‘Seems like they’re sleeping in pretty late for a Saturday.’

We were so dumb in those days it was ten minutes or thereabouts before we got anxious enough to investigate. Les’s bottom jaw fell so low, I thought maybe he was going to eat the handful of black feathers which was all we found.

Chord in E minor, please, maestro.

Well, there was only one crowd that was capable of a crime of this magnitude and that was the Victor Lynch boys. We both thought the same thing at the same time, but neither of us mentioned the dread name. In the end Les beckoned me to

follow him and when he finally stopped down by the rhubarb, he said, ‘Victor Lynch.’

I remember we sold our remaining sack of pine-cones that morning and we went to see a Hopalong Cassidy in the afternoon. We walked slowly and purposefully, loosely, ready to reach for our guns at the drop of a hat, speaking only in condensed, staccato bursts, these men are dangerous.

While we were in the theatre watching the screen grimly, Uncle Athol was raffling those fowls, twenty tickets a time, sixpence a knock, in the Federal Hotel. Whenever I hear that song, ‘I’ll be Glad When You’re Dead, You Rascal You’, I think of that man.

Theatre is dignifying Klynham’s cinema somewhat. It was a big draughty barn of a place, but many happy hours we spent therein. The building has had a great face-lift recently, but I recall it fondly the way it was in the days when Les and I sat enthralled by a serial picture called ‘The King of Diamonds’, and the kids stamped on the floor and whistled at each certificate of approval, unless it was a travel film and then they hooted and groaned. There was always a chance of my bare arm brushing against the electrically charged flesh of Josephine McClinton again as we crowded down the stairs at interval, or even maybe, some day, fluking a seat alongside her. There were big pictures of Tom Mix and Robert Montgomery and Dolores Del Rio and young Jane Withers on the walls of the stairway. My crush on Josephine was top-secret stuff, but Les and I openly admitted that we thought Jane Withers was a bit of all right, even if she did have a double chin. It was only puppy fat, Les reckoned.

After the flicks, Les and I cut out what was left of the cone money on a milkshake. We took our time and there were not many people left hanging around when we came out from the

soda fountain. We walked the length of the main street and we met Prudence.

At one end, the cinema end, of the main street, is a band rotunda into which people throw the paper off fish and chips. At the other end is a giant elm tree fenced off with wrought-iron railing. These two features of Klynham stare along the middle of the main street at each other in the frustrated but resigned manner of pensioned-off cannons in a park. The sun rises behind the elm tree and sets behind the band rotunda, its slanting rays at sundown imparting to this edifice a minaret-like appearance. At the western end are not only the band rotunda and the cinema, but also the billiard saloon. My big brother, Herbert, spent more time at the billiard saloon than he did up at our house on the corner of Smythe and Winchester streets. On Sundays, Herbert hung around the house and talked about the billiard saloon and people called Kelly and Jack Glenn and Hodson. The other end of the main street was, and still is, popular with the farmers on market days. They used to park their Dodge tourers around the big elm tree and sit on the running boards, or on the leaf-strewn, shadow-dappled grass and eat pies.

On the main street were two butchers’ shops with sawdust on the floors and one of these sold the finest sausages in the world it was generally understood. The other butcher had the best steak. Everybody knew that this was so. There could be no gainsaying it. Even the children knew that one butcher was renowned for his sausages and the other for his steak, because they had heard it stated so often and so positively by their elders. This conflicting appeal to patronage could complicate shopping, but we were unaffected inasmuch as only the sausage master was willing to extend credit to the Poindexter family. We were resigned

to gnawing away at the most gosh-awful steak. However, as Ma said, ‘What yuh lose on the swings yuh get on the rouseabouts.’ Good old Ma! There were several confectionery shops with counters and tables for sundae and milkshake consumers, a chemist, a saddlery, ironmongery, two grocery shops, two banks, and an old-established drapery business. Dabney’s, the undertaking and furnishing business, half-way along the street, was a very old-established firm, but it was shut as often as not; either that or there was no answer, and people never went there to buy furniture. They went to Hardley & Manning.

Hardley & Manning was our really big store and no shopping expedition was complete without using it as a short cut between two streets. The adventure of going right through Hardley & Manning, using it as a short cut, never palled. One emerged on a wide, dusty back street which commanded a fine view of the misty hinterland. It also featured the defunct Jubilee Hotel. There were three other hotels at Klynham, a number said by some to be ridiculous for the population while others bemoaned the days when there were four, before they shut down the Jubilee. Too many pubs or not, the big-bellied licensees, who wheezed masterfully in those open doorways were recognised as men of affluence, but they certainly spent no money having the litter swept up from the bare corridors between the bars. Except for the hotels, such two-storeyed buildings as the street boasted were unoccupied upstairs and some even had the top windows boarded up.

The main street always looked desolate at this hour on a Saturday as most of the shops closed at midday. Walking late on a Saturday afternoon the only person one could ever really count on meeting was Sam Finn, the local halfwit, another attraction

Klynham ran to in those days. Poor Sam Finn. When I think of him I feel as if I am looking back at the town through the wrong end of a telescope. And it feels odd to reflect that I, alone, probably hold the key to the secret of his disappearance, even the secret of his grave. But Sam Finn and the equally ill-fated Mabel Collinson, the music teacher, part and parcel of this story as they may be, will have to wait their cue. As I said the main street of Klynham looked desolate this Saturday after the cinema had closed. There was a sniff of dark smoke from the railway station in the air. The afternoon seemed reproachfully old. I would not have even seen Prudence who was diagonally across the intersection from us, I was still so burnt up about the raid, but Les nudged me and said, ‘That’s yuh sister, Ned.’

We stopped only because Les stopped, and Prudence came across the street slowly, shielding her eyes from the westering sun. When she reached the shadow of the big elm tree her squint became an engaging grin. She was two years older than me and she always looked to me as if she had a dirty face, but I realise now that everybody must have been right when they said she was ‘real pretty’. I think everybody was downright puzzled too at one of the Poindexter girls turning out a beauty, because no one else I can recall in the family was any oil painting.