A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future (20 page)

Read A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future Online

Authors: Daniel H. Pink

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Leadership, #Self-Help, #Personal Growth, #Success

“Leadership is about empathy. It is about having the ability to relate and to connect with people for the purpose of inspiring and empowering their lives.”

—

OPRAH WINFREY

But ten years later, the Conceptual Age is increasing the stakes. When Goleman wrote his book, the Internet was in its infancy and those highly skilled Indian programmers of Chapter 2 were in elementary school. Today, cheap and widespread online access, combined with all those overseas knowledge workers, are making the attributes measurable by IQ much easier to replace—which, as we have seen in earlier chapters, has meant that aptitudes more difficult to replicate are becoming more valuable. And the one aptitude that’s proven impossible for computers to reproduce, and very difficult for faraway workers connected by electrons to match, is Empathy.

Facing the Future

In 1872, thirteen years after he published

On the Origin of Species,

Charles Darwin published another book that scandalized Victorian society. The book was called

The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals—

and it made some controversial claims. Most notably, Darwin said that all mammals have emotions and that one way they convey these emotions is through their facial expressions. A dog with a lugubrious look on its face probably is sad, just as a person who’s frowning probably is unhappy.

Darwin’s book caused a stir when it came out. But for the next century it languished in obscurity. The assumption in the world of psychology and science was that our faces did express emotion—but that those expressions were products of culture rather than nature. But in 1965, Paul Ekman—then a young psychologist and now a legendary one—came along. Ekman, an American, traveled to Japan, Argentina, Brazil, and Chile. He showed people there photos of faces fixed in various expressions, and he found that Asians and South Americans interpreted the expressions the same way Americans did. He was intrigued. Perhaps these common interpretations were due to television or Western influence, he thought. So Ekman journeyed to the highlands of New Guinea and showed the same set of facial expression photos to tribespeople who’d never seen television, or even a Westerner, before. They read the faces the same way all of Ekman’s previous subjects did. And that led him to a groundbreaking conclusion: Darwin was right after all. Facial expressions were universal. Raising eyebrows indicated surprise in midtown Manhattan, just as it did in suburban Buenos Aires, just as it did in the highlands of New Guinea.

Ekman has devoted much of his career to studying facial expressions. He created the set of photographs that I looked at back in Chapter 1 when I was getting my brain scanned. His work is enormously important for our purposes. Empathy is largely about emotion—feeling what another is feeling. But emotions generally don’t reveal themselves in L-Directed ways. “People’s emotions are rarely put into words; far more often they are expressed through other cues,” writes Goleman. “Just as the mode of the rational mind is words, the mode of the emotions is nonverbal.”

2

And the main canvas for displaying those emotions is the face. With forty-three tiny muscles that tug and stretch and lift our mouth, eyes, cheeks, eyebrows, and forehead, our faces can convey the full range of human feeling. Since Empathy depends on emotion and since emotion is conveyed nonverbally, to enter another’s heart, you must begin the journey by looking into his face.

As we learned in Chapter 1, reading facial expressions is a specialty of our brain’s right hemisphere. When I looked at extreme expressions, unlike when I looked at scary scenes, the fMRI showed that the right side of my brain responded more robustly than my left. “We both express our own emotions and read the emotions of others primarily through the right hemisphere,” says George Washington University neurologist Richard Restak. That’s why, according to research at the University of Sussex, the vast majority of women—regardless of whether they are right-handed or left-handed—cradle babies on their left side. Since babies can’t talk, the only way we can understand their needs is by reading their expressions and intuiting their emotions. So we depend on our right hemisphere, which we enlist by turning to the left. (Recall from Chapter 1 that our brains are contralateral.)

3

People with damage to their right hemisphere have great difficulty recognizing the emotions on others’ faces. (The same is often true for those with autism, which in some cases entails a malfunction of the right hemisphere.) By contrast, people with damage to the left side of the brain—the side that, in most people, processes language—are actually

better

at reading expressions than the rest of us. For instance, both Ekman and Nancy Etcoff, a psychologist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, have shown that most of us are astonishingly bad at detecting when someone is lying. When we try to determine from another’s facial expressions or tone of voice if that person is fibbing, we don’t do much better than if we had offered random guesses. But aphasics—people with damage to their brain’s left hemisphere that compromises their ability to speak and understand language—are exceptionally good lie detectors. By reading facial cues, Etcoff found, they can spot liars more than 70 percent of the time.

4

The reason: since they can’t receive one channel of communication, they’re better at interpreting the other, more expressive channel.

The Conceptual Age puts a premium on this more elusive, but more expressive, channel. Endowing computers with emotional intelligence has been a dream for decades, but even the best scientists in the field of “affective computing” haven’t made much progress. Computers still do a shabby job of even distinguishing one face from another—let alone detecting the subtle expressions etched onto them. Computers have “tremendous mathematical abilities,” says Rosalind Picard of MIT, “but when it comes to interacting with people, they are autistic.”

5

Voice recognition software can now decipher our words—whether we tell our laptop to “Save” or “Delete” or whether we request “Aisle” or “Window” to an automated airline attendant. But the most sophisticated software on the planet running on the world’s most powerful computers can’t divine our emotions. Some newer applications are getting better at spotting the

existence

of emotion. For instance, some kinds of voice recognition software used in call centers can detect big changes in pitch, timing, and volume, all of which signal heightened emotion. But what happens when the software recognizes these signals? It transfers the call to an actual human being.

That example is a microcosm for work in the Conceptual Age. Work that can be reduced to rules—whether the rules are embedded in a few lines of software code or handed to a low-paid overseas worker—requires relatively little Empathy. Such work will largely disappear from countries like the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. But the work that remains will demand a much deeper understanding of the subtleties of human interaction than ever before. No surprise, then, that students at Stanford Business School are flocking to a course officially called “Interpersonal Dynamics” but known around campus as “Touchy-feely.” Or consider a field not typically known for emotional literacy—the practice of law. Much basic legal research can now be done by English-speaking lawyers in other parts of the world. Likewise, software and Web sites, as I explained in Chapter 3, have eliminated the monopoly lawyers once had on certain specialized information. So which lawyers will remain? Those who can empathize with their clients and understand their true needs. Those who can sit in a negotiation and figure out the subtext of the discussion that’s coursing beneath the explicit words. And those who can look at a jury, read their expressions, and instantly know whether they’re making a persuasive case. These empathic abilities have always been important to lawyers—but now they’ve become the key point of differentiation in this and other professions.

“People who lean on logic and philosophy and rational exposition end by starving the best part of the mind.”

—

WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS

But Empathy is much more than a vocational skill necessary for surviving twenty-first–century labor markets. It’s an ethic for living. It’s a means of understanding other human beings—as Darwin and Ekman found, a universal language that connects us beyond country or culture. Empathy makes us human. Empathy brings joy. And, as we’ll see in Chapter 9, Empathy is an essential part of living a life of meaning.

M

ANY OF

US

can boost our powers of Empathy. And nearly all of us can improve our ability to read faces. Over the years, Ekman has compiled an atlas of facial expressions—likely all the facial expressions that human beings throughout the world use to convey emotions. And he’s found that seven basic human emotions have clear facial signals: anger, sadness, fear, surprise, disgust, contempt, and happiness. Sometimes these expressions are full and intense. Many other times they are less conspicuous. There’s what Ekman calls the “slight expression,” which is usually the first prickle of an emotion or the failed attempt to hide that emotion. There’s the “partial expression.” And there’s the “micro expression,” which flashes across the face in less than one-fifth of a second and often occurs “when a person is consciously trying to conceal all signs of how he or she is feeling.”

6

Ekman has taught face-reading skills to agents from the FBI, CIA, and ATF, as well as to police officers, judges, lawyers, and even illustrators and animators. And now I’m going to teach you one aspect of Ekman’s techniques. (You can learn more of them in the Portfolio at the end of this chapter.)

I’ve always been irritated by what I think are fake smiles—but I’ve never been sure whether someone is grinning because he’s charmed by my wit or smiling precisely because he isn’t. Now I know. A smile of true enjoyment is what Ekman calls the “Duchenne smile,” after the French neurologist Duchenne de Boulogne, who conducted pioneering work in this field in the late 1800s. A genuine smile involves two facial muscles: (1) the zygomatic major muscle, which stretches from the cheekbone and lifts the corners of the mouth; and (2) the outer part of the obicularis oculi muscle, which orbits the eye, and is involved in “pulling down the eyebrows and the skin below the eyebrows, pulling up the skin below the eye, and raising the cheeks.”

7

Artificial smiles involve only the zygomatic major. The reason: we can control that muscle, but we can’t control the relevant part of the obicularis oculi muscle. It contracts spontaneously—and only when we’re actually experiencing enjoyment. As Duchenne himself put it, “The emotion of frank joy is expressed on the face by the combined contraction of the zygomaticus major muscle and the obicularis oculi. The first obeys the will but the second is only put into play by the sweet emotions of the soul.”

8

In other words, to detect a fake smile, look at the eyes. If the outer muscle of the orbicularis isn’t contracting, the person beaming at you is a false friend.

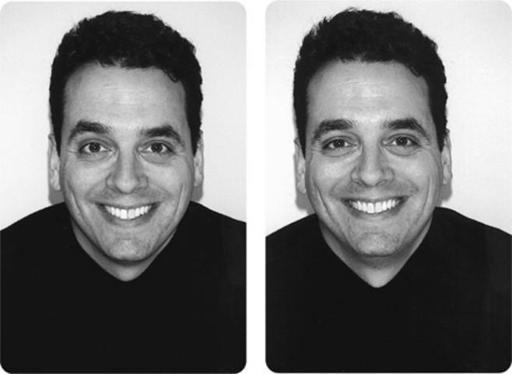

Here’s an example—two smiling photos of yours truly.

Can you tell in which one I’m squeezing out an insincere smile and in which I’m smiling in response to something funny my wife said? It’s not easy, but if you look carefully at my eyes, you can figure out the answer. The second photo is the true enjoyment photo. The eyebrows are a little lower. The skin under the eyes is pulled a little higher. The eyes themselves are bit narrower. In fact, if you cover up everything but the eyes, the answer is clearer. You just can’t fake a Duchenne smile. And while you can improve your empathic powers, you can’t fake Empathy either.

A Whole New Health Care

Empathy is not a stand-alone aptitude. It connects to the three high-concept, high-touch aptitudes I’ve already discussed. Empathy is an essential part of Design, because good designers put themselves in the mind of whoever is going to experience the product or service they’re designing. (It should be no surprise that one of the items in the Empathy Portfolio comes from a design firm.) Empathy is related to Symphony—because empathic people understand the importance of context. They see the whole person much as symphonic thinkers see the whole picture. Finally, the aptitude of Story also involves empathy. As we saw in the section on narrative medicine, stories can be pathways to Empathy—especially for physicians.

But Empathy is also reshaping medicine more directly. Several leaders in the medical field are urging that the profession shift its overarching approach from “detached concern to empathy,” as bioethicist Jodi Halpern puts it. The detached scientific model isn’t inappropriate, they say. It’s insufficient. As I’ve mentioned, much of medical practice has been standardized—reduced to a set of repeatable formulas for diagnosing and treating various ailments. While some doctors have criticized this development as “cookbook medicine,” it has many strengths. Rules-based medicine builds on the accumulated evidence of hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of cases. It helps ensure that medical professionals don’t reinvent the therapeutic wheel with each patient. But the truth is, computers could do some of this work. What they can’t do—remember, when it comes to human relations, computers are “autistic”—is to be empathic.