A World Lit Only by Fire (10 page)

Read A World Lit Only by Fire Online

Authors: William Manchester

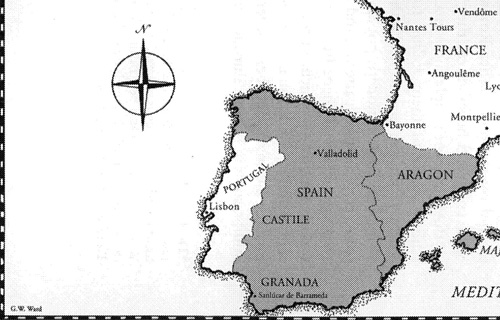

A voyager into the past would search in vain for the sprawling urban complexes which have dominated the continent since the

Industrial Revolution transformed it some two hundred years ago. In 1500 the three largest cities in Europe were Paris, Naples,

and Venice, with about 150,000 each. The only other communities with more than 100,000 inhabitants were situated by the sea,

rivers, or trading centers: Seville, Genoa, and Milan, each of them about the size of Reno, Nevada; Eugene, Oregon; or Beaumont,

Texas. Even among the celebrated

Reichsstädte

of the empire, only Cologne housed over 40,000 people. Other cities were about the same: Pisa had 40,000 citizens; Montpellier,

the largest municipality in southern France, 40,000; Florence 70,000; Barcelona 50,000; Valencia 30,000; Augsburg 20,000;

Nuremberg 15,000; Antwerp and Brussels 20,000. London was by far England’s largest town, with 50,000 Londoners; only 10,000

Englishmen lived in Bristol, the second-largest.

Twentieth-century urban areas are approached by superhighways, with skylines looming in the background. Municipalities were

far humbler then. Emerging from the forest and following a dirt path, a stranger would confront the grim walls and turrets

of a town’s defenses. Visible beyond them would be the gabled roofs of the well-to-do, the huge square tower of the donjon,

the spires of parish churches, and, dwarfing them all, the soaring mass of the local cathedral.

If the bishop’s seat was the spiritual heart of the community, the donjon, overshadowing the public square, was its secular

nucleus. On its roofs, twenty-four hours a day, stood watchmen, ready to strike the alarm bells at the first sign of attack

or fire. Below them lay the council chamber, where elders gathered to confer and vote; beneath that, the city archives; and,

in the cellar, the dungeon and the living quarters of the hangman, who was kept far busier than any executioner today. Sixteenth-century

men did not believe that criminal characters could be reformed or corrected, and so there were no reformatories or correctional

institutions. Indeed, prisons as we know them did not exist. Maiming and the lash were common punishments; for convicted felons

the rope was commoner still.

The donjon was the last line of defense, but it was the wall, the first line of defense, which determined the propinquity

inside it. The smaller its circumference, the safer (and cheaper) the wall was. Therefore the land within was invaluable,

and not an inch of it could be wasted. The twisting streets were as narrow as the breadth of a man’s shoulders, and pedestrians

bore bruises from collisions with one another. There was no paving; shops opened directly on the streets, which were filthy;

excrement, urine, and offal were simply flung out windows.

And it was easy to get lost. Sunlight rarely reached ground level, because the second story of each building always jutted

out over the first, the third over the second, and the fourth and fifth stories over those lower. At the top, at a height

approaching that of the great wall, burghers could actually shake hands with neighbors across the way. Rain rarely fell on

pedestrians, for which they were grateful, and little air or light, for which they weren’t. At night the town was scary. Watchmen

patrolled it—once clocks arrived, they would call, “One o’clock and all’s well!”—and heavy chains were stretched across

street entrances to foil the flight of thieves. Nevertheless rogues lurked in dark corners.

One neighborhood of winding little alleys offered signs, for those who could read them, that the feudal past was receding.

Here were found the butcher’s lane, the papermaker’s street, tanners’ row, cobblers’ shops, saddlemakers, and even a small

bookshop. Their significance lay in their commerce. Europe had developed a new class: the merchants. The hubs of medieval

business had been Venice, Naples, and Milan—among only a handful of cities with over 100,000 inhabitants. Then the Medicis

of Florence had entered banking. Finally, Germany’s century-old Hanseatic League stirred itself and, overtaking the others,

for a time dominated trade.

The Hansa, a league of some seventy medieval towns centering around Bremen, Hamburg, and Lübeck, was originally formed in

the thirteenth century to combat piracy and overcome foreign trade restrictions. It reached its apogee when a new generation

of rich traders and bankers came to power. Foremost among them was the Fugger family. Having started as peasant weavers in

Augsburg, not a Hanseatic town, the Fuggers expanded into the mining of silver, copper, and mercury. As moneylenders, they

became immensely wealthy, controlling Spanish customs and extending their power throughout Spain’s overseas empire. Their

influence stretched from Rome to Budapest, from Lisbon to Danzig, from

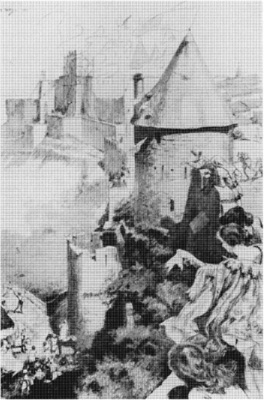

A sixteenth-century town wall

Moscow to Chile. In their banking role, they loaned millions of ducats to kings, cardinals, and the Holy Roman emperor, financing

wars, propping up popes, and underwriting new adventures—putting up the money, for example, that King Carlos of Spain gave

Magellan in commissioning his voyage around the world. In the early sixteenth century the family patriarch was Jakob Fugger

II, who first emerged as a powerful figure in 1505, when he secretly bought the crown jewels of Charles the Bold, duke of

Burgundy. Jakob first became a count in Kirchberg and Weisser-horn; then, in 1514 the emperor Maximilian I—

der gross Max

—acknowledged the Fuggers’ role as his chief financial supporter for thirty years by making him a hereditary knight of the

Holy Roman Empire. In 1516, by negotiating complex loans, Jakob made Henry VIII of England a Fugger ally. It was a tribute

to the family’s influence, and to the growth of trade everywhere, that a year later the Church’s Fifth Lateran Council lifted

its age-old prohibition of usury.

Each European town of any size had its miniature Fugger, a merchant whose home in the marketplace typically rose five stories

and was built with beams filled in with stucco, mortar, and laths. Storerooms were piled high with expensive Oriental rugs

and containers of powdered spices; clerks at high desks pored over accounts; the owner and his wife, though of peasant birth,

wore gold lace and even ignored laws forbidding anyone not nobly born to wear furs. In the manner of a grand seigneur the

merchant would chat with patrician customers as though he were their equal. Impoverished knights, resenting this, ambushed

merchants in the forest and cut off their right hands. It was a cruel and futile gesture; commerce had arrived to stay, and

the knights were just leaving. Besides, the adversaries were mismatched. The true rivals of the mercantile class were the

clerics. Subtly but inexorably the bourgeois would replace the clergy in the continental power structure.

T

HE TOWN, HOWEVER

, was not typical of Europe. In the early 1500s one could hike through the woods for days without encountering a settlement

of any size. Between 80 and 90 percent of the population (the peasantry; serfdom had been abolished everywhere except in remote

pockets of Germany) lived in villages of fewer than a hundred people, fifteen or twenty miles apart, surrounded by endless

woodlands. They slept in their small, cramped hamlets, which afforded little privacy, but they worked—entire families, including

expectant mothers and toddlers—in the fields and pastures between their huts and the great forest. It was brutish toil,

but absolutely necessary to keep the wolf from the door. Wheat had to be beaten out by flails, and not everyone owned a plowshare.

Those who didn’t borrowed or rented when possible; when it was impossible, they broke the earth awkwardly with mattocks.

Knights, of course, experienced none of this. In their castles—or, now that the cannon had rendered castle defenses obsolete,

their new manor houses—they played backgammon, chess, or checkers (which was called

cronometrista

in Italy,

dames

in France, and draughts in England). Hunting, hawking, and falconry were their outdoor passions. A visitor from the twentieth

century would find their homes uncomfortable: damp, cold, and reeking from primitive sanitation, for plumbing was unknown.

But in other ways they were attractive and spacious. Ceilings were timbered,

A medieval fair: customers, cloth merchants, a beggar, a draper’s shop, a money-weigher, mountebanks

floors tiled (carpets were just beginning to come into fashion); tapestries covered walls, windows were glass. The great central

hall of the crumbling castles had been replaced by a vestibule at the entrance, which led to a living room dominated by its

massive hearth, and, beyond that, a “drawto chamber,” or “(with)drawing room” for private talks and a “parler” for general

conversations and meals.

Gluttony wallowed in its nauseous excesses at tables spread in the halls of the mighty. The everyday dinner of a man of rank

ran from fifteen to twenty dishes; England’s earl of Warwick, who fed as many as five hundred guests at a sitting, used six

oxen a day at the evening meal. The oxen were not as succulent as they sound; by tradition, the meat was kept salted in vats

against the possibility of a siege, and boiled in a great copper vat. Even so, enormous quantities of it were ingested and

digested. On special occasions a whole stag might be roasted in the great fireplace, crisped and larded, then cut up in quarters,

doused in a steaming pepper sauce, and served on outsized plates.