A World Lit Only by Fire (43 page)

Read A World Lit Only by Fire Online

Authors: William Manchester

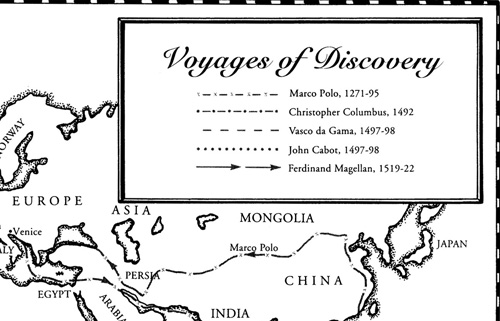

Rutters were copied by hand and translated under supervision, but those opening new trade routes never reached the hands of

printers. They were too precious. Some were sold. Others were declared to be state secrets; divulging their contents was punishable

by death, for a rival captain with a rutter in his cabin could exploit another’s dearly bought knowledge. Once a way had been

found, dangers were minimal, but the perils of the original explorers can scarcely be exaggerated.

It is a remarkable fact that virtually all of them came from one corner of Europe. Portugal and Spain had contributed little

to Western civilization before then. In the five centuries since then they have produced several brilliant artists; apart

from that, their achievements have been less than awesome. But this, incontestably, was Iberia’s hour. Within thirty years

—a single generation—a few hundred small ships weighing anchor in Lisbon, Palos, and Sanlúcar discovered more of the world

than had all mankind in all the millennia since the beginning of time.

T

HE FIRST

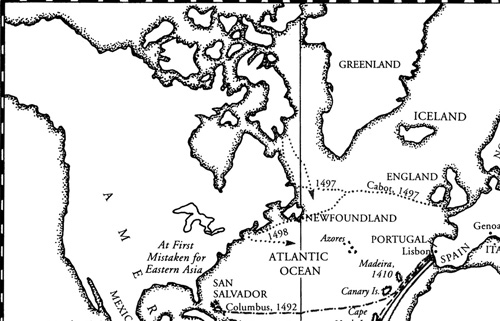

probing voyages were cautious, even hesitant, and in perspective their accomplishments seem slight. In 1460, when Prince

Henry died, Portuguese mariners had made only six unimpressive discoveries: three small archipelagoes off their own coast

—the Azores, Madeiras, and Canaries—and, in northern Africa, Cape Verde’s fertile promontory, the Senegal River, and the

port of Ceuta. The prince had been in his grave eleven years when João de Santarém became the first European to cross the

equator and return unscathed. Another eleven years passed before Diogo Cão found the mouth of the Congo River. Finally, in

1486, a half-century after the prince’s first expedition, Bartolomeu Dias made a major discovery. Struggling through a mighty

storm, he rounded the southern tip of Africa. He was anxious to sail on, convinced that India lay ahead, but his exhausted

men forced him to return home. There King John II, after congratulating him, named the tip the Cape of Good Hope. To Dias’s

dismay, however, his countrymen were indifferent to the implications of his rutter—an all-water route to India, outflanking

the Middle Eastern merchants dealing in spices, perfumes, silks, drugs, gold, and gems.

Six years later the initiative passed to Spain, whose Castilian adventurers, having completed their conquest of the Moors’

last stronghold, were ready for new challenges. Because Arab traders had passed along fragments of Asian geography, Europeans

had a general idea of the continent’s chief coastal features: India, China, Japan, the East Indies. Paolo Toscanelli, a Florentine

scholar, had concluded that the Orient lay only 3,000 nautical miles west of Lisbon. Toscanelli strengthened the confidence

of Genoa’s Christopher Columbus. Columbus had raised 500,000 maravedis for an expedition. He won over Louis de Santangel,

Spain’s royal treasurer, and Santangel persuaded the crown to invest another 1 million maravedis—roughly $14,000—in a

Columbian attempt to reach the East by crossing the Atlantic.

Off the Genoese seaman went, navigating by dead reckoning and, legend has it, crying to his men, “

Adelante! Adelante!

” (“Forward! Forward!”). Returning early in 1493, he electrified Christendom by reporting complete success. In Barcelona Isabella

and Ferdinand held a grand reception for him. Honoring him with the titles Viceroy of the Indies and Admiral of the Ocean

Sea (

Almirante del Mar Océano

), they told him to organize more expeditions to the Orient. Actually he couldn’t. He had found, not Asia, but the Bahama

island of San Salvador. He refused to abandon his claim to the discovery of Cathay, however, and although he returned to the

New World three times, he never changed his mind. He called the natives he encountered Indians, which is why the Caribbean

Islands have been known as the West Indies ever since. In 1496, he was unable to sail around Cuba. His officers explained

that they were thwarted by bad weather, but Columbus rejected the explanation. The real reason, he said, was that they were

lying off an Oriental peninsula. He thought it was probably Malaya.

His claims continued to be accepted. In Lisbon King Manuel, ascending the throne in 1495, assumed that the Spaniards had stolen

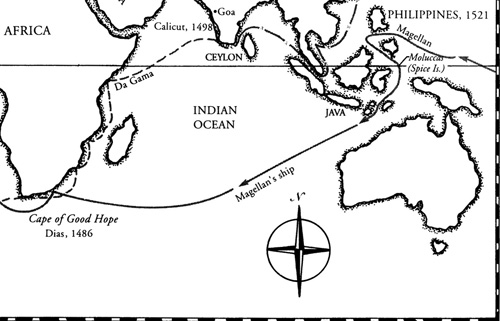

a march on him. Jealous, and aware of the pleas of Bartolomeu Dias, he gave Vasco da Gama four vessels and instructions to

reach India via the Cape of Good Hope. Da Gama is not among the attractive figures of the age, although in many ways he was

typical of it. Brawny, brutal, cruel, and vindictive, he sought to dominate strange lands by terrifying the inhabitants. Once

he deliberately set fire to an Arab ship, burning alive some three hundred passengers, including women and children. Nevertheless

he earned the rank of

almirante

, bestowed upon him by his grateful sovereign, for Portugal’s rise as a world power owed much to him. On November 22, 1497,

he rounded the cape Dias had found. Equipped with an Arab map and accompanied by an Arab navigator, he pushed on, first reaching

Mozambique and Kenya on Africa’s east coast, and then, after a twenty-three-day run across the Indian Ocean, Calicut on the

southwest shore of India.

T

HE

P

ORTUGUESE

had finally found a new passage to India, one free of the costly transshipment and tolls exacted by the old routes from Egypt,

Arabia, and Persia via Italy. For more than a century the economic consequences of this commercial revolution—for that is

what it amounted to—were more spectacular than the discoveries of Columbus and his successors in what was coming to be known

as the New World. While Spanish navigators were floundering about in the Caribbean “Indies,” the vaults of Lisbon’s banks

were filling up with profits from the new trade. Indeed, until the turn of the sixteenth century the Portuguese scarcely thought

of the possibilities lying on the far side of the Atlantic and even then Manuel’s ministers were preoccupied with the markets

created by vessels doubling the Cape of Good Hope.

Afonso de Albuquerque took office as governor of Portuguese India in 1509. His duties were more military than civil; fighting

Hindus and Muslims, he captured and fortified both Goa and, on the Arabian coast, Aden; then he landed on Ceylon and moved

on to seize Malacca on the Malayan Peninsula, the center of the East Indian spice trade. From Malacca alone he sent home $25

million in loot. His Excelência roamed all over the underbelly of Asia. He dispatched twenty ships to the Red Sea, and, in

1512, planted Manuel’s colors in Celebes and the Moluccas. The Portuguese expansion continued to pick up momentum; in 1516

Duarte Coelho opened Thailand and southern Vietnam to Portuguese commerce, and the following year Fernão Peres de Andrade

reached trade agreements on the Chinese mainland with both Peking and Canton.

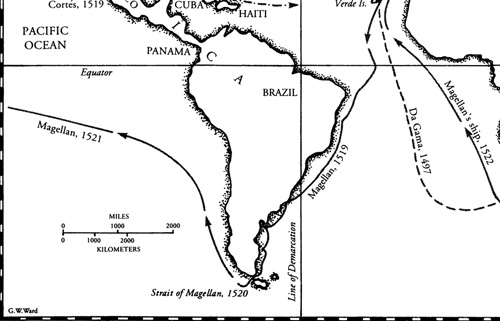

Half a world away, Columbus had continued to make one landing after another in the New World, sending back reports on his

increasing knowledge of the Orient. However, there was a growing suspicion among the mariners who had followed in his wake

that they were not in Asia at all. By the late 1490s landings had been made in Honduras, Venezuela, Newfoundland, and on the

North American mainland. In 1500 Gaspar Côrte-Real reached Labrador, and that same year Pedro Cabral, storm-driven from a

course he had set for the Cape of Good Hope, stumbled upon Brazil. Cabral hoisted Portugal’s colors over Brazil; Vicente Yáñez

Pinzón claimed it for Spain.

With the discovery of Panama, Colombia, and the mouth of the Amazon, a very long coastline had begun to take shape. It remained

for Amerigo Vespucci, a Florentine merchant in the service of the Medicis, to define the emerging truth. In Spain on business,

Vespucci had caught the exploration fever and sailed westward under the Portuguese flag. Later, in a letter to Italian friends,

he wrote that on June 16, 1497, during one of his four expeditions to what he called the

novo mondo

, he had touched the mainland of a new continent. Although doubt was later cast on this claim, both Columbus and the Spanish

government, which awarded Vespucci a lifetime appointment as

piloto mayor

—chief of Spain’s pilots—believed him reliable. In April 1507 Martin Waldseemüller, professor of cosmography at the University

of Saint-Dié, produced the first map showing the Western Hemisphere. He called it “America,” and thirty years later Gerardus

Mercator followed Waldseemüller’s precedent, though by then it was clear that the New World comprised more than one continent.