A World Lit Only by Fire (46 page)

Read A World Lit Only by Fire Online

Authors: William Manchester

Delighted with the weather and the local women, the fleet’s crews would have preferred to linger in Rio indefinitely, but

their leader ordered them to hoist sail; according to Schöner’s globe, the Río de Solís, as the Río de la Plata was then called,

lay a thousand miles to the south, and he was impatient to find his priceless paso. After hugging the shore for two weeks,

the flagship, with the other vessels streaming behind, passed the cape of Santa María and then, just beyond a low hill which

they christened Montevidi—today Montevideo, Uruguay—lookouts sighted the great estuary. The men, seeing that it was impossible

to glimpse a far shore, cheered lustily; without exception, Pigafetta wrote, they believed this to be the mouth of the legendary

strait. Their leader was sure of it, convinced that here, where Juan Díaz de Solís had died less than four years earlier,

lay the inlet which would lead him to Balboa’s Mar del Sur and, six hundred leagues to the west, the coveted, disputed Spice

Islands.

H

IS DISCOVERY

of his crushing error came gradually, like a man’s realization that he has irrevocably lost his most prized possession. It

has to be here, he tells himself, or, I left it there; it

must

be

somewhere

. The fact that it is forever gone is insupportable at first;

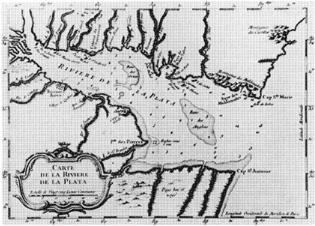

The Río de la Plata, from an early atlas

acceptance of the disaster comes slowly, accompanied by a sickening feeling of emptiness. So the bleak truth must have come

to Magellan. Despite Faleiro’s calculations, Schöner’s globe, Behaim’s map, and the fourteen-year-old Portuguese pilots’ rutters

in Lisbon’s Tesouraria, the capitán-general had found, not a strait, but only an immense bay. He was nothing if not stubborn.

For nearly a month he explored and reexplored the Plata, desperately trying to find an opening and always failing. Finally,

on Thursday, February 2, 1520, he abandoned hope. Once that happened—once he grasped the implications of his defeat—the

depth of his grief can only be imagined. It meant that his every Valladolid assurance, given in good faith to King Carlos

and his privy council, had been false. He could share his disappointment with no one; if his Castilian captains knew the truth,

they would clap him in irons, lock him up in the flagship’s brig, and return him to Spain, a defrocked Knight Commander of

Santiago charged with fraud, imposture, and extortion of royal funds. Abandoning his search was therefore out of the question.

Like Cortés at Veracruz, he had burned his boats. A return to Portugal, where he was wanted for treason, was also out of the

question. Either he found glory, or disgrace—and execution—would find him.

The strait, if it existed, could only lie to the southwest; thus his future, if he had one, also lay there. In the first week

of February, without a word of explanation to his baffled officers and men, who knew only that their destination was the balmy

south seas, he led them crawling through treacherous currents and surging tides, down the desolate, barren, and increasingly

bitter Patagonian coast toward antarctic latitudes, praying that his dream would be redeemed by the reach around the next

cape, or the next, or the one after that. Every harbor, every cove was scouted, with his leadsmen taking soundings, till shoals

forced him to quit and move on to the next inlet. On February 24 his hopes rose in the Golfo San Matías. He sent parties of

men in ship’s boats to search thoroughly. They did, but returned weary and dejected, having found nothing. The Bahía de los

Patos followed, then the Bahía de los Trabajos and the Golfo San Jorge. All ended in disappointment.

Each day the weather grew more depressing. No European had ever been this close to the South Pole.

*

The days grew shorter, the nights longer, the winds fiercer, the seas grayer; the waves towered higher, and the southern

winter lay ahead. To grasp the full horror of the deteriorating climate, it is necessary only to translate degrees of southern

latitude into northern latitude. Rio de Janeiro, where they had first landed, is as far below the equator as Key West is above

it. By the same reckoning the Río de la Plata is comparable to northern Florida, the Golfo San Matías to Boston, and Puerto

San Julián, which they reached after thirty-seven days of struggling through shocking weather, to Nova Scotia. The sails of

their five little ships were whitened by sleet and hail. Cyclones battered them twice a week or more. Both forecastles and

after-castles had been repeatedly blown away on every vessel and replaced by ship’s carpenters. Crews shrank as the corpses

of men pried loose from frozen rigging slid to briny graves. Yet the paso remained as elusive as ever.

In dismal, chilly, miserable Puerto San Julián, having inched down 1,330 miles since leaving the Río de la Plata, Magellan

decided to hole up in winter quarters. They had reached the forty-ninth parallel—the forty-ninth degree of south latitude.

There, on Saturday, March 31, he told his royal captains that he meant to continue south until he had found the strait, even

if it took them below seventy degrees. Some thought they heard him promise to turn back if their frustration continued as

far down as seventy-five degrees south latitude, but if he said it, he cannot have known what it meant; at that parallel the

fleet would have been frozen fast in what is now the Antarctic’s Weddell Sea. Nevertheless his mood was undeniably implacable.

Sunday morning—Palm Sunday—he reduced bread and wine rations for all hands. Almost certainly he intended to provoke revolt.

He was aware that the tinder was there, awaiting a spark. There were Spaniards in the crews who were loyal to their Castilian

officers. And the dons, he knew, were in an ugly mood. On Monday he summoned them to dine with him. Their refusal was curt.

It was a

desafio

, a challenge; in effect they had thrown down the gauntlet. And that evening, April 2, 1520, they mutinied.

T

HEY CAME AT NIGHT

—thirty armed Spaniards in a longboat, led by Juan de Cartagena, Antonio de Coca, and Gaspar de Quesada, rowing with muffled

oars toward

San Antonio

, the largest ship in the fleet. King Carlos’s privy council would have been surprised to know that Cartagena no longer commanded

the ship. In Valladolid the planners of the expedition had envisaged the capitán-general on the quarterdeck of the flagship

Trinidad

, with the Castilians commanding the other four. But once at sea, Magellan, exercising his supreme powers as admiral, had

begun switching skippers. Now, six and a half months after their departure, a Portuguese officer, Álvaro de Mesquita, one

of Magellan’s cousins, conned

San Antonio

. Only

Concepción

and

Victoria

remained in the hands of the dons. If Cartagena could regain his old command, however, the mutineers, controlling three vessels,

could bar the way to the open sea and hold their admiral at bay. And aboard

San Antonio

, all hands were asleep. Why Magellan had not alerted Mesquita and ordered him to post guards is puzzling. Ordinarily he was

the most vigilant of leaders, and the omens of trouble had been unmistakable. Perhaps he could not believe they would actually

rebel. They were, after all, well-bred aristocrats, who had sworn holy oaths of obedience in Seville. And treachery was not

only a capital offense; it was also shameful. He may also have doubted their resolve. In the coming days they were, in fact,

to prove irresolute, but at the outset they moved with confidence, swarming up rope ladders and boarding the big ship, which

quickly became their prize. Mesquita awoke to find himself surrounded by men with drawn swords, and, moments later, manacled

and confined to the purser’s cabin. Until now the coup had been bloodless. Then Mesquita’s officers, wakened by the tumult,

demanded an explanation, and one of them, the ship’s master, Juan de Elorriaga, roughly challenged the mutineers. Quesada

and his servant knifed Elorriaga six times; the officer fell to the deck mortally wounded. That ended the resistance. After

clapping all crewmen loyal to Magellan in irons, the mutineers broke into the storeroom and issued wine to the rest of the

men. Quesada remained aboard and brought Juan Sebastián del Cano over to serve as master. The others quietly returned to their

own ships.

Tuesday morning Magellan rose as usual, unaware of any change in his command. He was soon to be enlightened. In winter quarters

the fleet’s daily routine began with dispatching a ship’s boat ashore. Its mission there was to fetch water and wood for all

five vessels, each of which contributed men to the working party. When the boat reached

San Antonio

, its bos’n was vexed to find no rope ladder lowered and no crewmen ready to join him. He angrily called for an explanation

and was told that the ship was now under the command of Capitán Gaspar de Quesada, who no longer honored orders from the “

así llamado

” (“so-called”) capitán-general. The bos’n hastily returned to

Trinidad

. Magellan calmly instructed him to tour the other vessels, demanding pledges of loyalty.

Victoria

and

Concepción

refused. Only

Santiago’s

Serrano, Spanish but loyal, swore that he would remain so.

Thus the lines of battle were drawn. In any fight

Santiago

—at seventy-five tons the smallest of the five—would be quickly sunk. The flagship could not continue round the world

alone. The admiral seemed checkmated, but his dilemma over the paso—not to mention his temperament—meant that yielding

was out of the question. Now, as so often, patience was his sheet anchor. He quietly awaited word from the rebels. When that

word arrived—in the form of a letter from Quesada, speaking for the others—it revealed their pathetic weakness. Their

noble birth was to be their undoing after all. The letter expressed no wrath, no piratical defiance; there was no ultimatum,

nor even a list of demands. Instead the dons were submitting a

suplica

, a petition. On reflection they had decided to acknowledge his supreme authority, as conferred by their sovereign. In their

subordinate role they merely asked for better treatment at his hands, a little respect for their high birth, and some information

about his plans, particularly how he proposed to reach the Spice Islands. All this was set forth in the most florid, most

oleaginous Spanish prose.

Mutineers may command, but they cannot beg. Their strength derives from force alone; if they disavow it, they are naked. Magellan

now had their measure; with audacity, he could regain control of his fleet. He knew the rebel captains expected him to lunge

toward

San Antonio

. The ship’s size argued for that; so did his cousin’s imprisonment there; so did the presence on its quarterdeck of Quesada,

now the chief conspirator. Therefore Magellan, knowing the value of the unexpected, decided to retake

Victoria

, whose Castilian commander was the less formidable Luis de Mendoza. The counterattack would be made by two longboats. The

larger boat, with the wind at its back, would carry fifteen heavily armed men led by Duarte Barbosa. To lead the other, smaller

craft the admiral picked Gonzalo Gómez de Espinosa, the fleet’s master-at-arms and commander of its marine guard. Gómez’s

crew consisted of only five men, but its mission was crucial—to strike the first blow and thereby create a diversion.