A Young Man's Passage (15 page)

Read A Young Man's Passage Online

Authors: Julian Clary

FIVE

‘The supreme object of life is to live . . .

It is true life only to realise one’s own perfection,

to make one’s every dream a reality. Even this is possible.’

OSCAR WILDE

HETEROSEXUAL SEX WAS

a revelation to me. So snug, warm and wet – I was full of admiration for Nature’s cleverness. I mastered the basic manoeuvres of intercourse in the missionary position, but the taking of the vagina from behind, known rather sordidly as ‘doggie position’, soon became a firm favourite. I also learned how important it is in the straight world to sustain sexual activity and not peak before your partner is ready. This I achieved by reciting mathematical tables (not out loud, though). Another useful trick was to sign my name, imagining the penis is a pen. Whether this works with anyone else’s name other than my own I couldn’t say, but the unpredictable twists and turns of writing ‘Julian Peter McDonald Clary’ with such a novel instrument certainly had the desired effect. The female orgasm (unless she was acting) was a Dyson to the male carpet sweeper, a whooping cough to our throat clearing. What with nipples and breasts, secretions, G-spots and sundry other erogenous zones to discover and excite, it’s a wonder I ever bothered with men again. The female body is peppered with erogenous zones. To me, as a beginner, it was a bit like learning to fly a helicopter; I didn’t know where to begin.

Of course, we didn’t attempt any preliminary lessons in the scout hut. We waited until we got back to London and the privacy of my room at Hardy Road. The world of boy/girl romance was suddenly revealed to me. That was it, we were lovers. We lay in bed half the day eating boiled eggs and listening to ‘Cool For Cats’ by Squeeze. If she was woken early by the concert violinist who lived next door, she opened the sash window in my bedroom and shrieked, ‘Stop that bleedin’ racket!’ On Valentine’s Day she gave me a card in which she’d written:

I can’t resist your silky style

The diamonds in your head

And though you are a super star

You bring me tea in bed.

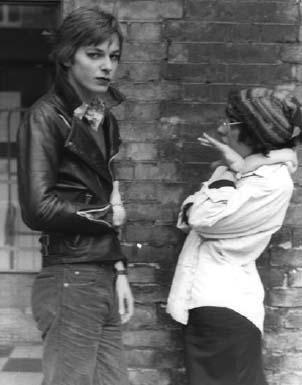

I shall call her Michelle. We had been flirting with each other for weeks before it all began. I had announced one day that I was contemplating a love affair to see me through the winter. Who did she suggest? ‘Me,’ she answered firmly. She had big brown eyes, and although she didn’t exactly stare at me she would, I noticed, rest her eyes upon me. During rehearsals we had sometimes held eye contact for a little too long. Now we were embarking on something major. At that age you don’t analyse things much, but it was hardly practical: I was gay and she had a boyfriend. But she was an alpha female, not to be denied, and I was besotted. For her birthday I gave her some big brass earrings. On one was engraved: ‘Will you marry me?’ On the other was: ‘Why ever not?’ I think we both knew we were doomed in the romantic longevity stakes, but we were helpless. We couldn’t do without each other.

The arrangement was she slept with me during the week and her boyfriend at weekends. Clothes and toiletries accumulated at my place for weekday convenience, and for four days a week I was her man. Her ritual weekend defection to the ‘other’ boyfriend became the source of some unhappiness. Consequently I was always a bit tortured on Friday, but all smiles by Tuesday. Eventually I grew accustomed to the arrangement. Secretly I rather admired Michelle’s refusal to adhere to social convention, although when a third suitor entered the fray I think we all felt a trifle mucky. We struggled gamely on for a few months, but it wasn’t fun any more.

I remember taking a suitcase full of her clothes over to her flat towards the end and emptying them on her front doorstep. There were tears and tantrums. We never quite let go of each other, and even these days, 24 years later, although we see each other from time to time, we do not socialise with each other’s husbands or discuss our personal lives. When I look into Michelle’s eyes, my heart still races and I imagine a life other than the one I have lived. I have never reprieved my heterosexual life, or dabbled again in that procreative world. I have thought of it – sometimes longed for it – but it has not come to pass. Those sacred, carnal pastures belong to Michelle alone. Once you become a renowned homosexual you subconsciously, if not culturally, feel obliged to keep within those boundaries. And if your sexuality is your career, or at least a defining aspect of it, you do not ask any questions.

I do not cast any doubt on my homosexuality (Lord knows, we’ve all got better things to do with our time) but in analysing my life for your reading pleasure, my relationship with Michelle must be given its due. It was a happy, if emotionally stirring, interlude in this my gay life thus far.

AT THE TIME

I didn’t dwell on things for too long. I wrote some dreary poems, but soon after our affair petered out I returned to the gay world with an enthusiasm that surprised even me. I got a job as a bar man at Heaven nightclub behind Charing Cross station. Taking a handsome boy home after work wasn’t so much a perk, more a part of your job description. My job there came to an end on ‘toga night’. As is not uncommon on such themed nights, all the bar staff wore minimal loincloths to help the atmosphere along. A crusty old punter draped in a beer-stained sheet leered at me all evening then asked me, ‘Is it yes or no?’ Once I understood that the question requiring an answer was whether I was his for the night, I answered in no uncertain terms and he complained to the management. The next night the manager, David Inches, ‘let me go’.

My days at Goldsmiths were nearly over, too. I wrote to my parents: ‘No one talks about anything but exams and work and what they’re going to do afterwards. Whatever will become of me? I change from being worried and depressed about it, seeing myself ending up as a disillusioned teacher or office worker, to being very excited, thinking that now is the time I’ve been waiting for, and now it all happens.’

After university the plan was to get acting work. We signed on the dole, sent hopeful letters to the National Theatre and the RSC, and got a few dismissive replies. In those days you couldn’t get far without an Equity union card. Linda and I got our provisional card by doing Glad and May gigs wherever anyone would take us. Old people’s homes provided us with a few of the required contracts, although the old dears weren’t terribly taken with us. They watched our nonsense for a few minutes then started playing cards.

On my 21st birthday Linda and I did a Glad and May gig in a pub somewhere in Shepherd’s Bush. As it was a special occasion we got a taxi back to Hardy Road from Blackheath Station. I paid for the fare with our wages – a £50 note, and, without noticing, got change for a fiver. Linda wasn’t pleased.

After pestering the local paper we got some publicity. ‘Cheek and chat are where it’s at,’ announced the entertainment page of the

Lewisham Gazette

. ‘Gaudy, fast-talking housewives Glad and May have found just what they wanted in a nervous pub customer’s handbag.’ Our big break, or so we thought, was a centre spread in the

Sun

on 17 July 1980. ‘Come to the Cabaret!’ wrote Roslyn Grose. ‘All over Britain song-and-dance is coming up on the menu nearly as often as fish and chips. Glad and May are a pair of housewife superstars who would make Dame Edna Everage gnash her dentures with envy. They’re so young and pretty they make other women feel nervous – especially when they nudge each other and ask: “Feel like a rummage?”’ Someone recognised me in the newsagents and I was thrilled.

To make the most of this national coverage we put an advert in the

South-East London Chronicle

saying, rather naively, ‘Glad and May, Housewives Extraordinaire, will entertain you at your office party’. I only got one call, from an Indian man, who asked what the show entailed.

‘Well,’ I said, ‘we come out dressed as two char ladies talking about our lives.’

‘And then?’ he asked.

‘Well, then we turn into Amanda and Elyot from

Private Lives

.’

‘And then?’ he said, breathlessly.

‘Then we sing a song and do a handbag competition.’

‘And then? S-s-sex cabaret?’ he whispered hopefully.

I hung up.

I remember a few of our gigs. The Queen’s Head, a tiny pub in Steine Street, Brighton. We were introduced by Simon Fanshawe, who said afterwards, ‘There are two things going to happen to Julian. Firstly, he’s going to become a huge star. Secondly, he’s going to be seeing a

lot

more of me!’ One out of two isn’t bad.

We were also booked for a Saturday night at the famous, if notoriously rough, south London drag pub the Vauxhall Tavern – home for 15 years to Lily Savage. Booked to do half an hour, we only had 20 minutes of material, so I asked my old schoolfriend Nick, now a graduate of the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, to warm up the crowd with a few show tunes. We were all in a state of terror beforehand. Nick sought comfort in a bottle of sherry before he went on. After a couple of numbers the crowd were turning ugly. Nick’s microphone was unceremoniously unplugged and Lee Paris, the resident compère, introduced us.

‘We’ve got something a bit unusual for you now, ladies and gentlemen – a double act, one of whom is a real live woman!’ The audience growled their disapproval. We raced through the act getting no laughs at all, and in no time were into the handbag competition. There weren’t many on offer but we grabbed what we could. Linda opened hers first and pulled out a letter. ‘Oh, look!’ she said, ‘her husband’s in Pentonville Prison!’ We both knew it wasn’t wise, but it was too late to do anything but read on – a harrowing, personal letter from an incarcerated husband to his darling wife. Desperately trying to squeeze some comedy out of the letter, we sounded suspiciously like two inexperienced students making fun of a sad, private communication.

‘’Ere, Glad, I wouldn’t mind being banged up, how about you?’

‘Oh no, May! I was sent down once and it left a terrible taste in my mouth!’

That’s when the ice cubes started to be thrown. A slow hand-clap started at the back of the pub and swiftly gained momentum. The burly woman who owned the bag stood at the front punching her fist into the palm of her other hand. We hurriedly retreated to the dressing room where we stayed long after closing time in case we were lynched.

MEANWHILE, WE SCOURED

the back pages of the

Stage

where acting jobs were advertised. There were lots of profit-share companies doing group-devised plays that would tour the outer reaches of Wales, or worthy theatre-in-education productions funded by the GLC. Sometimes we’d get an audition. Linda got lucky first, a contract for a year’s work with the Chipping Norton Repertory Company, strangely enough the very place my great-grandmother came from. I went to quite a few auditions but rarely got a re-call. Not only was I extremely uncomfortable and nervous when expected to impress a panel, but my languid mannerisms and breathy voice, let’s face it, excluded me from most roles. I didn’t really go in for versatility. But eventually my persistence paid off. My first job was with the Covent Garden Community Theatre. Legend has it that just as I started my audition speech a shaft of sunlight broke through the window and gave me an ethereal glow. The panel of jolly left-wing types thought I was some kind of Second Coming and gave me the job on the spot.

The show was called

I Was A Teenage Sausage Dog

, written and directed by Andy Cunningham. I was to play Auntie Vera. It wasn’t glamour drag: I wore a rainbow-coloured Afro wig, a woollen minidress and Dr Martens boots. Aimed at children, it was an anti-vivisection romp about Vera’s dog Fluffy Wuffles (played by a collie puppy called Georgia Georgio) being pursued by evil scientists who wanted to perform unspeakable experiments on him.

We rehearsed in the Holy Trinity church hall, opposite Holborn tube station. The acting style was loud and cartoon-like and we performed in community centres, adventure playgrounds and the occasional London pub, travelling round in a battered red van. As soon as we were all on board and en route to our first gig of the day, a joint would be rolled and passed around. To begin with I was worried about my promise to my mother, and about fainting again, so I just mimed my inhalations. Soon enough, however, I got the idea and the weeks passed in an amiable, stoned haze. But this was just the start. We also took our show off to various summer hippy fairs, such as the Elephant Fayre in Suffolk. Drugs of every sort were all the rage there, of course, and along with everyone else I took magic mushrooms and LSD, which made the corn in the fields turn a heavenly yellow and the sky blood-red. ‘Ooh! Aaah!’ we all said. I also remember joining the queue outside a caravan. ‘Cocaine £1 a line’ read the advert, written in felt-tip on a torn piece of cardboard. Taking drugs at that time among those people was commonplace. I remember going to see an acupuncturist and being asked if I’d had any drugs in the last week, and proudly giving a very extensive response: ‘Marijuana, speed, cocaine, mushrooms, Valium and temazepam.’ It didn’t occur to me that if I’d cut out all the substances, I’d have had no need of the treatment for exhaustion in the first place.