A Young Man's Passage (35 page)

Read A Young Man's Passage Online

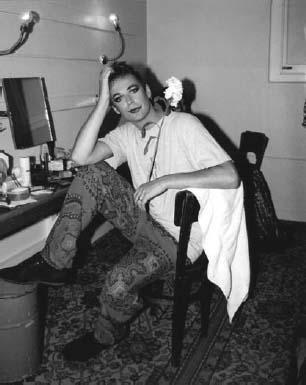

Authors: Julian Clary

Feel like escaping, running away.

9 December 1993

Again, Rohypnol in attendance. Just want to note the interesting thing I’ve done today: transferred all the Mikos trauma to Christopher, which is the underlying reason for such disproportionate drama anyway and is somehow easier to cope with. Just the occasional (if I’m strict!) pang.

Went to the doctor yesterday. Valium and Rohypnol. I cried. I’ve been quite a worry all round.

11 December 1993. Swindon

Arrived at my parents’ and burst into tears on the doorstep. My mother looked shocked and pulled me to her then whisked me upstairs. I know I have driven Mikos away with my tears and traumas. Why do I care so much? Why am I tortured with thoughts and memories? I’m dreadfully restless.

Psychic Penelope paid a visit this morning (I think my friends are on a rota system, keeping watch). She said my heart was numb. My brain is, too, but Valium is better than the panicky madness. She quoted a Chinese proverb, along the lines that you have to set someone free then they can come back and you have to set them free again. But I don’t think Mikos will be back. ‘You’re going from bad to worse,’ he said the other day.

13 December 1993. Middleton Grove

Extraordinary fuss in the tabloids about my remarks on the British Comedy Awards last night. Front page of the

Mirror

,

Sun

and

Star

.

Mirror: ‘GAY CLARY’S SICK TV GAG.’

Star: ‘LAMONT GAY JIBE BY CLARY ROCKS TV AWARDS.’

Sun: ‘OBSCENE. STORM OVER GAY CLARY’S SEX JIBE AT LAMONT.’

Said I’d just been fisting him in the wings. (The set looked like Hampstead Heath, you see. The punchline was ‘Talk about a red box . . .’ but I don’t think it registered after the F word.)

Anyway, attempted a writing session for the second series of

Terry and Julian

with Paul Merton and John Henderson, but was too Valiumed to achieve much. Passed Mikos as I drove down Camden Road. He was waiting for a bus, hood pulled up as it was raining and lighting a cigarette.

Then it was the new Comedy Store opening in Oxenden Street. Had a great time in the dressing room with Paul and everyone. Paul was very sweet and concerned about me. He surreptitiously got me to eat something, I noticed. Compèred part two.

Then home and there was a message from Penelope telling me it was a new moon. Feeling stronger.

SO THERE WE

have it. I thought I should put the infamous Norman Lamont incident in context for you. Taxi drivers reminisce about it still, punters in supermarkets tell me where they were and who they were with as if it was the day Elvis or President Kennedy died. It was just a joke, a daring one perhaps. Nowadays it is widely perceived as the moment my career was derailed; I had crossed the line and gone too far. LWT issued a kind of fatwa banning me from live television for evermore. A retrospective documentary about gay comics I saw on Channel 4 recently made it sound as if I was dead. ‘The first soldiers always fall . . .’ said some pompous talking head. He seemed to imply my downfall was necessary to pave the way for Brian Dowling to host kiddies’ TV. Well, that makes it all worthwhile. The real wonder is that I was able to come up with such a top-notch joke while in such a dysfunctional state. I have learned to live with it, of course, and cannot regret something that has given so much pleasure to so many. Boy George likened it to his ‘Sex? I’d rather have a cup of tea!’ remark. We will never escape our infamy, and fully expect it to feature in our obituaries when the time comes. Incidentally, fisting isn’t an exclusively ‘gay’ activity, whatever the press may tell you. It’s an activity open to anyone lucky enough to be born with a hand and an arsehole.

But because I was so engulfed with melancholy at the time, so drugged with Valium and alcohol, it does not evoke happy memories for me. I finish the book here at what was for some a deserved public dishonouring in the tabloids, and for others just a jolly good laugh. But it was a pivotal moment, let’s face it, and I’m sure the reader appreciates the drama of such a signing off as much as I do. In the context of the times I can now see that fame uncentred me, love distracted me and rejection unbalanced me. You live and learn.

What you do need to know is that my malaise passed eventually and I recovered. But not before I sold the house in Holloway, put everything in storage, had some counselling, went on another five-month tour of Australia and a twelve-month course of Prozac. Apart from the occasional panic attack I was fine. (A chat show with Ruby Wax, Ivana Trump and Dana International, for example. Well, wouldn’t you panic?)

When I returned I bought a house back in jolly Camden Town where happiness reigns. I aspired to it as a teenager and as soon as I moved there I knew I had found my spiritual home. Somehow, at the age of 13, I knew I wanted to live in Camden Town and drive a Citroën 2CV. I think Nick and I had been to the market one weekend, and where the 2CV fantasy came from I don’t recall, but I think it’s more to do with ley lines and ancient pagan goings-on. Such things are not for analysing. Best just to go with the flow. I flirt with Norfolk, Majorca and Brighton, but only in Camden does the never-specified tribal contentment settle over me. I know what’s what there. The tweeness of Primrose Hill and the desolate harshness of Kentish Town fill me with horror. As soon as I enter my safe half-square mile, I know the gods are with me. This is also where Christopher and Fanny reside. Whether they could face a move, I’m not sure. But it’s them I scurry home to.

The front door bell went yesterday. I picked up the intercom.

‘Sorry to bother you,’ came the voice of a young Scottish woman, ‘but I wonder if you’ve got any steel cutters I could borrow? Only my car’s been clamped outside, and as the clampers are shut the police told me I should just get something to cut it off with.’

‘I’m sorry. I’ve only got a pair of scissors.’

I met a former neighbour from Holloway in the street one day. She’d lived opposite me in Middleton Grove, and I would often see her standing in the street outside her house gazing up at the ornamental turrets on my roof. I asked her what she’d been staring at all those months ago. ‘I sometimes thought I saw a girl’s face peering out through the little window,’ she said, spookily, a bit like Fraser from

Dad’s Army

. ‘We locals refer to your house as “Lover’s Leap” . . .’ It seems no one has been happy in that house either before me or since. Indeed, I’ve seen it for sale in the window of Hotblack Desiato every year or so since I sold it.

Things will never get that bad again, I’m glad to say. The pendulum swings back and forth until it stops. The extremes are no longer as far reaching. I have learned to be suspicious of negative thoughts and to remove myself from suspect environments. I protect myself these days.

EPILOGUE

‘Memories are the specific invisible remains

in our lives of what belongs in the past tense.’

JANET FLANNER, PARIS WAS YESTERDAY

MAYBE, IN THE

course of this book, I’ve gone too far. Tales of sex, drugs and private anguish are usually kept, if not from the family, then at least from the public. This has obviously not been the case with this particular book. Or, let’s face it, with what one might loosely describe as my ‘act’. We should none of us feign surprise. I have never aspired to cautiousness. Never mind. There’s been a lot of dirty washing down the old Ganges since 1993. Keeping quiet about the years since then is my attempt at discretion. For the moment, anyway.

‘He talks a lot about sex in his act, but not a mention of love,’ wrote Lynn Barber in an

Observer

article. There was some confusion in my mind those days, as I recall, between love and sex. Of course, a good seeing to, expertly administered, can be a real tonic. A glint in the eye, a spring in the step, an aura of well-being, not unlike visiting Stonehenge, all these can be ours from a stranger. A gift from the Gay God. Not love, of course, but better than watching television or eating food covered in breadcrumbs.

As for drugs, well, I’ve been there, as you know. You don’t work in television for years without being lured into the occasional toilet cubicle for a line of cocaine refreshment, at the very least. If it hasn’t happened you know you’re doing something wrong.

I’ve moved on since the days when a puff of a joint caused me to faint, and can acknowledge that drugs, be they paracetamol, alcohol or speed, have their uses. I saw it as self-medication at the time, but found out the hard way that there’s a price to pay. If you go up you must come down, and although one dealt with the inevitable depression a gram of coke delivered a day or so later, dismissing the sudden emotional earthquakes for the chemically induced nonsense they were, I must, in my mature years, question whether or not the whole experience was worth it. There’s a lot to be said for a clear mind and a fresh face. Drink the water, swallow the green tea, just say no.

As for private anguish, these days I simply repeat to myself as a mantra the words of retired actress Norma Talmadge to an autograph hunter: ‘Go away, dear. I don’t need you any more.’

The sense of destiny I sought at the beginning of this book has not emerged with any clarity, I’m sorry to report. It was far too lofty and philosophical a question to get a clear answer to anyway. The wisdom of my own creation remains a well-kept secret. I just turned up, I guess.

Which brings me back to my parents.

I was filming a while ago in a dogs’ grooming parlour. It was part of another quality light entertainment television show called something like ‘Celebrities Behaving like Dogs’, that was simply too exciting to go into. Bouncing around the parlour was a young kitten, white legs and underbelly, tortoiseshell back and cheekbones. She bounded towards my dog Valerie and me with all the enthusiasm and charisma of David Bowie. She was bright and attractive. I could see at once she was a special cat. ‘Looking for a home,’ said Meg, mistress of the parlour, a pleasing 25-year-old. Turns out the kitten was abandoned by the occupiers of a neighbouring squat during the drama of a recent police raid. Who knows what left-wing, communal, free-loving, drug-induced social structure had created this extraordinary creature? Half cat, half socially skilled hippy, she crashed into me, the epitome of life: bold, adventurous, funny.

Gloria wouldn’t welcome a sister, so I called my parents and planted the idea of a fun-loving kitten in need of a home.

‘I haven’t been able to sleep,’ said my mother the next day.

‘You realise this kitten might well outlive us?’ said my father.

A few days later I delivered the kitten to them. Now they’re obsessed. They call her ‘Puppy’ and follow her wherever she goes as if they were Moonies. ‘The kitten’s on the windowsill . . . She’s looking outside!’ they tell me, breathless, over the phone.

The first time she was allowed into the garden they both went with her. Ashen-faced, my father turned to my mother. ‘She’s gone in the hedge!’ They watch her every move.

‘She’s such a curious cat, we’re worried she’ll wander off or someone will steal her.’