A Zombie's History of the United States (11 page)

Read A Zombie's History of the United States Online

Authors: Josh Miller

That famous rallying cry was used by the Texian Army to embolden its soldiers by reminding them of the cruelty that the Mexican troops under President General Antonio López de Santa Anna had shown to the Texians at the Battle of the Alamo. Santa Anna’s siege on the Alamo Mission lasted thirteen days, from February 23 to March 6, 1836 (1836 was a leap year).

We must remember that at its conclusion, all of the Texian defenders had been killed. We must remember that Santa Anna refused to take prisoners.

This imagery of the Mexican Army’s heartless slaughter of brave men inspired a new wave of support for the Texian cause, from both Texas settlers and United States citizens. Bolstered by this collective need for vengeance, the Texians defeated the Mexican Army on April 21 that same year at the Battle of San Jacinto. The revolution was won. Then the famous rallying war cry became something of a community maxim, bonding the people of Texas.

We must remember what we had to go through to get here.

All these calls for remembering are extremely ironic, considering that the Mexicans never killed any Texians at the Alamo. When Santa Anna and his men entered the mission on March 6, they discovered the Texians already at the losing end of a bloody struggle against…

Zombies.

Everyone Wants Independence

The Mexicans do not know the undead as we do.

—Stephen F. Austin, Texas colonist, letter to the Texian Convention, April 1833

When the Mexican War for Independence (1810-1821) threw off the shackles of Spanish colonialism, the fledgling nation of Mexico rose from New Spain’s ashes and the former province of Spanish Texas became part of the new larger state of Coahuila y Tejas. The new Mexican government initially encouraged immigration from the United States, but when English speakers soon outnumbered the Mexican-born citizens by almost four to one, the government put a ban on further immigration to Tejas. With this off-balance demographic, conflict was inevitable.

The English-speaking Texians were unhappy about many things: Mexico did not believe in freedom of religion—only in the Roman Catholic Church. The government dictated what crops the settlers should grow. With Mexico bankrupt from the revolution, in most areas settlers were forced to create their own militias to protect against hostile Indians and zombies. Yet Mexico did not allow wanton killing of zombies, nor did they allow slavery (though both laws were readily ignored by the many Texians). The areas that did have garrisons were stocked with convicted criminals (given the choice between prison or the army). And the new capital, Saltillo, was in southern Coahuila, more than 500 miles away.

ZOMBIE CORRALS

The Roman Catholics in Mexico had very different feelings about zombies than Americans did, perhaps because they did not have as large a zombie population to contend with. In 1761, Pope Clement XIII had proclaimed that zombinated individuals were souls caught in purgatory, or something similar to limbo, forced to remain on earth until they had “walked away their sins.” Thus killing a zombie was tampering with the Lord’s work, and a crime.

The Spanish, and then the Mexicans, would capture and place their sparse zombie population into secured locations, or zombie corrals, as the Texians called them. The Mexican government expected the Texians to do the same but without providing the military muscle needed in the more densely zombie-populated northern Tejas area. In May 1834, a Texian farmer named Mitchell Zerda de-animated his zombinated wife, for which he was arrested. Though he was eventually set free with no punishment, his brief imprisonment and the public outcry over it was one of the many inciting incidents that lead to the Texas Revolution.

In April 1833, Texian settlers formed a convention, electing Stephen F. Austin (for whom the current Texas capital is named) to carry a message to Mexico City. The message was a proposed state constitution, affecting political policies and granting Tejas separate statehood from Coahuila. Mexican President Santa Anna flatly refused the separate statehood, and Austin was jailed when he wrote a letter suggesting Texians take action unilaterally. Things escalated further when Santa Anna dissolved Mexico’s constitution in early 1835 and shifted the government from federalism to centralism. By October of that year, the Texas Revolution was officially under way.

Digging In

You may all go to Hell with the undead and damned, and I will go to Texas.

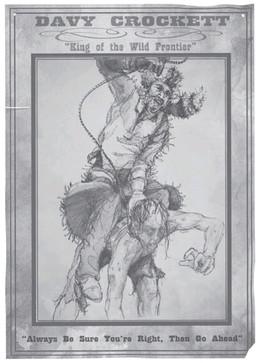

—Davy Crockett, to members of his Tennessee congressional district, 1835

After the Texian Army had forced Mexican troops to vacate San Antonio de Béxar (now just San Antonio), Texian soldiers established a garrison at the Alamo Mission, originally a Spanish religious outpost that had been converted into a zombie corral by the Béxar community. The zombies inside were de-animated one by one with bullets to the skull and removed from the compound. The mission sprawled over three acres, with 1,320 feet of perimeter in need of defense. An interior plaza was bordered on the east by a chapel, from which the two-story Long Barracks extended north. The walls surrounding the complex were at least 2.75 feet thick and 12 feet high at various sections. Originally designed by the Spanish to keep zombies out, the Béxar people had ironically retrofitted the Alamo to keep the zombies in, but neither group had designed it to stand against an artillery-equipped army.

Texian engineer Green Jameson installed nineteen cannons along the walls. Though Jameson bragged that they could now “whip 10 to 1 with our artillery,” the Texian position at the Alamo was still very poor. With fewer than one hundred soldiers remaining at the fort by January 6, 1836, Col. James C. Neill, the acting commander of the Alamo, wrote to Sam Houston (one of four men laying claim to command of the Texian Army) asking for assistance. However, Houston felt the Alamo was not worth the manpower needed to defend it. So he sent Col. James Bowie with thirty men to remove the artillery and then destroy the Alamo—while not worth defending, there was also no reason to let the Mexicans have it.

James “Jim” Bowie was a frontiersman and soldier. He had risen to a level of international notoriety in 1827 following his famous Sandbar Fight. The Sandbar incident started as a typical duel, until several zombies attacked the participants. When his gun jammed, Bowie single-handedly killed all the zombies with his hunting knife, jamming it into their skulls and decapitating one. How much of this story is true we do not know, but Bowie soon became legendary, as did his knife, which he superstitiously carried with him everywhere. Bowie called his knife “Skuller.” So identified did Bowie become with the knife that replicas became incredibly popular. To this day the model is known as a Bowie knife.

Col. Neill appealed to Bowie not only to leave the artillery he had been sent there to retrieve, but to stay and fight as well. Perhaps drawn by the call of adventure, Bowie accepted. In a letter to Governor Henry Smith, Bowie said:

Colonel Neill and myself have come to the solemn resolution that we will rather die in these ditches than give it up to the enemy. Let them come and try us. They shall receive a most warm welcome from Skuller.

Bowie was not the only legendary figure at the Alamo who had answered the call of adventure. On February 8, a small group of volunteers arrived to give support, including David “Davy” Crockett. Crockett was a politician and living American folk hero, famous for his self-hyping tales of frontier exploits, such as his classic boast:

I’m Davy Crockett, fresh from the backwoods, half-horse, half-alligator, a little touched with the snapping turtle, can wade the Mississippi, leap the Ohio, ride upon a streak of lightning, and slip in and out an Undead’s mouth without nicking its teeth!

Advertisement for a public appearance by Davy Crockett, 1829.

On February 11, Neill received orders to report to another command. Before leaving, he transferred leadership to cavalry officer William B. Travis, who ended up sharing command with Bowie, who had been elected by the men. The two men did not get along, but they were forced to put aside their differences on February 23 when Mexican troops were seen approaching Béxar. Residents fled the city, and members of the garrison who had been living in town were forced to scurry their wives and children into the Alamo with them. Within hours Béxar was occupied by 1,500 Mexican troops.

The Siege

Lets us let those believe what they are want to about the Alamo.

—Sam Houston, letter to the commanders of the Texian Army, March 1836

The first several days of the siege were without much incident. Mexican soldiers established artillery batteries about 1,000 feet from the Alamo and launched cannonballs into the mission’s plaza. There were no Texian casualties. Travis ordered that the cannonballs be reused and shot back at the Mexicans. When Mexican soldiers crossed the San Antonio River and took cover in some abandoned structures near the Alamo, several Texians ventured out and burned the structures down. A brief skirmish followed in which two Mexicans were killed and several more wounded. There still were no Texian casualties.

In fact, the only ill tidings within the Alamo walls had been when Bowie collapsed during dinner from illness. The two doctors on hand were unable to determine what malady Bowie was suffering from, but it was serious enough that Travis had to assume sole command of the garrison. Bowie thought that Travis must’ve poisoned him, jotting in his journal “that great horse apple wanted me out the way.” Though outside of Bowie’s fevered paranoia, most scholars have never given the idea much credit. Whatever the case, Bowie was to remain bedridden for the remainder of the siege.

By March 3, almost 2,000 extra Mexican soldiers had arrived at Béxar. Travis was frantically sending out messages to nearby Texian garrisons, but help was simply not coming. There had still been little in the way of actual battle or Texian death. One soldier went missing in the night, which Travis recorded as a deserter, but Bowie recorded this ominous version:

My fever were so high sleep would not come last night. Rolled on my cot in my sweat listening to the Mexicans cannons. Fnally, I was near drifting when I heard the groans. I sat up. Groans, still. Faint but there. I grabbed Skuller from my pillow and climbed from the cot. Walking was hard and I could scarsly hear over my own weezing but I continued after the groans. It sounded almost below me and I found a door with stairs led down. I swear the groan was down there. Then the dammed medic spotted me and forced me back to bed, ignoring my telling of the groan. A soldier was sent to look after the stairs. Now this morn they say this same soldier run off. I called on damm Travis to tell him but he gave me a look as though I got mad with fever. I know what I heard.

On March 4, reinforcements finally arrived but a far smaller force than Travis had been hoping for, and they arrived with no heavy artillery. A twelve-pound cannon was expected to arrive on March 7, which would be one day too late, as Santa Anna announced to his men that they were going to attack on the morning of March 6. Though as it would turn out, Santa Anna would be too late as well.

On the night of March 5, Santa Anna ordered a halt to his artillery bombardment. His plan was to let the Texians get lulled by the calm, then strike while they were all asleep. In the early hours of March 6, gunfire was heard from the Alamo, but as Santa Anna’s men readied to return fire, they realized none of the firing was being directed toward them. Screams were echoing up from within the mission’s walls. The chaos ended at 6:30 a.m., the Alamo going silent.

When Santa Anna and his men finally managed to break through the Alamo’s main gate, all they found were dead bodies—dead soldiers everywhere. Most of the women and children had gathered in the safety of the church, though some also lay strewn amongst the carnage. Santa Anna was shocked when the women and children broke down in relief upon the sight of the Mexican soldiers, so scared had they been that they praised the Lord upon seeing their enemy. None of them could quite explain what had happened, but zombies were involved. Yet the zombies were all on the ground too, de-animated.