A Zombie's History of the United States (13 page)

Read A Zombie's History of the United States Online

Authors: Josh Miller

Once becoming hybridized many hybrids committed suicide, either of their own accord or under influence of their church officials, who assured them it was their only hope of regaining entrance into heaven. Many others fled to the western frontier to become a problem for the Indians. Some simply found ways to conceal their secret. Most were caught and destroyed. Regardless, the hybrid strain was here, and it was here to stay.

Zombies in Chains

The moving dead are our Nation’s mightiest resource and still unrealized in full.

—Robert La Jogne, South Carolina senator, 1808

From the moment Europeans first encountered zombies, they had attempted to put the creatures to profitable use. Zombies were disastrous as a tool in warfare, and though there was a trade in zombie prostitution, it was hardly a widespread practice. Given the high cost of importing and maintaining slaves from Africa, it was inevitable that some enterprising individuals would attempt to use zombies as manual labor.

Most people were not crazy enough to attempt working alongside a zombie in any capacity; that is, until 1807, when Calvin Moore created a simple and effective zombie muzzle. Getting the muzzle on the zombie wasn’t exactly easy, but once it was fastened in place, it rendered a zombie virtually harmless. Following the mass production of Moore’s muzzle, there was a zombie slavery boom.

Zombie slaves were used for a variety of tasks. They were chained to posts amongst crops to serve as scarecrows, and chained to perimeter fences to deter the escape of human slaves. They were fastened to yokes and used to till and plow fields, to pull carts and wagons, and used to turn grinding wheels in mills. Zombies could not be whipped or given orders, but by placing human bait in front of them, they would struggle forward indefinitely, no matter the weight placed against them. In fact, zombie slaves were so ideal that many plantation owners would intentionally zombinate their African slaves to make them easier to control. This practice was illegal and generally frowned upon by the public, but the law was rarely ever enforced.

Regardless of the effectiveness of Moore’s muzzle, with so many zombies near so many humans day in and day out, accidents had to happen. Muzzles would break, or a zombie claw mark might lead to zombination. In 1820, a faulty muzzle accident struck the North Carolina farm of Tom Hunter. All of the farm’s twenty-one residents were either devoured or zombinated, and four other humans died after the zombies spread from the farm—it was the worst in a long line of similar accidents. Following the tragedy, North Carolina passed a “deficiency law” requiring plantation and farm owners to have two living slaves for every undead one. Over the course of the next few years, other states followed North Carolina’s example, adopting their own variations of deficiency laws (South Carolina required only one human slave for every five zombie slaves).

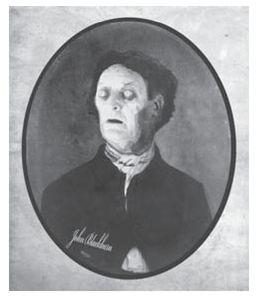

Pictoral accompanying an article about zombie labor from the

Virginia Farmer’s Gazette

, May 1844.

By the mid-1800s, zombie slavery had become a way of life in the South. Northern zombie slavery abolitionists saw the practice not only as unsavory and embarrassing to the American character, but also dangerous. The First Cleanse in 1751 had removed a massive number of zombies from the colonies, and though the number of undead had increased during the tumult of the Revolutionary War, the overall numbers had still remained lower than what they had been prior to the cleanse. Now southern plantations had systematically increased the number dras tically. The population of the United States in 1860 was 31,443,321. Of that, 5,600,142 were slaves: 3,953,760 human, 1,646,382 zombie.

HYBRID SLAVES

In 1845, a hybrid named Porter Wallace was arrested in Georgia when his family discovered what he was, after Wallace perplexingly survived being impaled on a wooden beam during a silo explosion. Instead of being terminated by flame or firing squad, as was the general practice, Wallace was purchased as a slave by William Alme, a cotton plantation owner. Presumably picking cotton seemed an acceptable alternative to Wallace when compared with being burnt alive.

In general, hybrids were not very desirable as slaves, seen as too intelligent and temperamental (i.e., dangerous) compared with their predictable zombie brethren. Slavery versus death was a choice given to many captured hybrids, but unlike zombies, hybrids would eventually seek to escape. Zombies could also be starved for incredibly long periods of time, often over a year, before they finally beca me too weak to work. Hybrids potentially could go as long, but they would be driven to unmanageable fleshlusts from hunger after a few weeks.

Slavery supporters argued that the zombies were well controlled, posing no danger to anyone. Statistically this was generally true. Accidents were still routine, but given the immense number of zombies in the South, they were less frequent than one might have expected. Slave owners could also have made the argument that zombies were closer to animals than their human slaves, and thus not actually slaves at all, but doing so would have been admitting there was something questionable about keeping human slaves in the first place. So zombie and human slavery remained intertwined for both slavery proponents and opponents alike.

Zombie abolitionists were faced with a fairly sizable roadblock to their cause: the million and a half zombie slaves in the South could not simply be “freed.” The ensuing human slaughter would have been legendary. Marron Ross, a Pennsylvanian Quaker and zombie abolitionist, had a similar theological take on zombies as the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico. He thought it was clear that zombies were humans stuck in a kind of limbo, but unlike the Mexicans, he thought it was our duty to send them on their way through de-animation. Ross made it the subject of a short paper he published in 1854, titled

Thoughts on What to be Done With the Trouble of the Walking Damned in America

. The paper and its contained philosophy were widely embraced by the abolitionist movement.

The Civil War had already been raging for two years when, in January 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, an executive order, which declared the freedom of all slaves in ten specific states of the Confederacy. The proclamation did not name the slave-holding border states of Kentucky, Missouri, Maryland, or Delaware, who had never declared secession. As to what “freedom” meant for the zombies:

And be it further enacted, That all undead slaves of persons who shall hereafter be engaged in rebellion against the government of the United States, or who shall in any way give aid or comfort thereto, escaping from such persons and taking refuge within the lines of the army; and all undead slaves captured from such persons or deserted by them and coming under the control of the government of the United States; and all undead slaves of such person found or being within any place occupied by rebel forces and afterwards occupied by the forces of the United States, shall be deemed captives of war, and shall be forever free of their servitude, and mercifully put to immediate termination; may their souls rest with God.

Zombie slavery proponents laughed off Lincoln’s order, quickly dubbing it the “Emaciation Proclamation.”

John Blackburn

The living man’s happiness cannot be purchased by the dead man’s misery.

—John Blackburn, A Narrative of the Life of John Blackburn, an UnDead American, 1853

John Charles Blackburn was born in Talbot County, Maryland, in 1820, the average human son of a successful lawyer. Blackburn remained an average human, himself going into law, until July 1846, when he was attacked by a zombie-human hybrid while coming home from a tavern. Blackburn successfully fought off his attacker, but not before he was bitten. Afterward, Blackburn and his family did their best to hide his hybridity. He carried on with his burgeoning law career, drinking cups of human blood periodically to satiate his cravings—his parents or two brothers generously donating the blood.

Who knows how long things could have carried on like this, but when John’s father offered him a partnership in the family law firm, passing over John’s older brother George, an embittered George anonymously reported John to the authorities. John Blackburn was promptly arrested and sent to trial. Had Blackburn not been a lawyer, and a clever lawyer at that, he would surely have been sent to the courthouse’s pyre and been lost to history like countless hybrids before and after him. Fortunately for Blackburn, and for history, he

was

a lawyer, and he

was

clever.

Blackburn chose to represent himself, not wanting his father to have to tarnish his image by defending a hybrid. The prosecution of hybrids had never been particularly airtight in a legal sense. Blackburn knew this, and he argued that there was nothing in the American law books that stated being a hybrid was illegal. The trial ended with a hung jury and major headlines. Did Maryland not have the right to prosecute hybrids for being monsters? This was something that had many citizens concerned. When Blackburn’s case was retried, the state brought in Andrew Holton, a prosecutor with an impressive track record of successful wins.

Daguerreotype of John Blackburn, 1853.

Holton had Blackburn sent to a medical examiner, who testified in court that Blackburn did not have a heartbeat. Holton concluded before the jury that this was evidence that Blackburn was legally dead, and thus had no rights; he, in fact, did not even have the right to the trial they were all party to. Blackburn then countered:

If, as you say, good prosecutor, I am dead, then I am a corpse, speaking before you all. We could argue the relative and observable logic of this, but as the prosecutor wishes to wade in the technics of our law, I am eager to oblige him. It may interest the good prosecutor to know—as it would appear he is not fully current in his quotable knowledge of our laws—that in the fine state of Maryland it is illegal—I repeat—illegal to desecrate a corpse, for any purpose. And just four years ago this very court determined that the corpse of a local cooper was property of his widow. So, on top of the for-mentioned legality, it would appear that burning me up would be destroying the property of my surviving family, which I assure you, would upset them immensely.

When this trial too ended with a hung jury, the case was not retried. As a major victory for a hybrid, Blackburn was also now a minor celebrity. Despite unchanged views toward hybrids, Blackburn became a popular lecturer and guest at society functions. He was paid handsomely to tell his story in

A Narrative of the Life of John Blackburn, an UnDead American

, which shot his star even higher. He was the first openly revealed hybrid invited to the White House. Blackburn even married a human, Michelle Lagerholm, a wealthy German shipping heiress.

Blackburn championed hybrid awareness and rights and became a figurehead in the zombie slavery abolitionist movement, particularly as the editor of the abolitionist newspaper,

The Morning Star

. Though Blackburn always took pains to separate hybrids from zombies—“I would not confuse a human with an ape, though I have seen both chew a banana; I would think my people deserve similar respect.”—he was staunchly against zombie slavery. Blackburn was savvy of the fact that people’s fear of zombies fed directly into their fear of hybrids. Blackburn’s many detractors accused him of wanting the zombie slaves freed so he could use them to enslave humanity, but in reality he was a very vocal proponent of Marron Ross’s de-animation plan.