Ace of Spies (24 page)

Matters were pre-empted in a dramatic and totally unforeseen way, when, on 30 August, Leonid Kannegiser, a Workers’ Popular Socialist Party activist, shot dead Moisei Uritsky, head of the Petrograd Cheka. That same day, in a completely unconnected incident, Fanya Kaplan, a member of the Social Revolutionary Party, shot Lenin as he left a meeting at the Michelson factory in Moscow. Lenin survived, but only just. Of the two shots fired at point-blank range, one missed his heart by less than an inch and the other missed his jugular vein by a similar margin.

These unconnected events were now knitted together by the Cheka to implicate and link Bolshevism’s many opponents into one giant conspiracy that warranted the unleashing of a full retaliatory response. The ‘Red Terror’, as it came to be known, resulted in over a thousand political opponents being summarily rounded up and shot. The Cheka raid on the British Embassy in Petrograd resulted in the death of Cromie, who apparently put up resistance. Using a list supplied by Berzin, the Cheka also rounded up those who were involved in the ‘Lockhart Plot’ and more besides. Lockhart was arrested, although later released in an exchange for Litvinov, who had been arrested in London in reprisal. Elizaveta Otten, Reilly’s lover and chief courier, was also arrested, along with his other mistress Olga Starzheskaya. Maria Fride, one of Kalamatiano’s couriers, was also arrested at Otten’s flat with a set of papers she had brought for Reilly. Olga later related the story of her arrest in a petition to the Red Cross Committee for the Aid of Political Prisoners:

I was arrested at VTsIK where I had worked at the Administrational Section since May. A day before, at night, my flat was searched but nothing was confiscated, and nobody was arrested. The reason for my arrest is known to me and is as follows: my groom Konstantin Markovich Massino, who I deeply loved and intended to share my life with, proved to be Englishman Reilly, who participated in the Anglo–French plot.

Throughout our acquaintance he gave himself out for a Russian, and it was shortly before his disappearance that he told me who he really was. Until that moment I had no doubts he was Russian. I believed him and loved him, regarding him as an honest, noble, interesting and exclusively clever man, and in the deep of my heart I was very proud of his love. Therefore I was horrified by what I discovered about him during the interrogation. There proved to be two completely different persons. The deception, dirt and mean behaviour of this man pained me enormously. I have learnt about this ploy only from the papers. He never told me anything about it. Moreover, he seemed to me to be a supporter of Soviet power, though we never had any serious political discussions, as I was exclusively engaged in the settlement of my personal life, a new flat, household and work matters. My interest in politics was merely superficial. Throughout my stay in Moscow, and before that, I was never involved in any illegal organisations and made no statements against the existing order; moreover, I always supported Bolshevism and Communism as I understood it, and all those who knew me used to call me a Bolshevik.

33

Elizaveta Otten also petitioned the committee:

I was arrested on 1 September for my acquaintance with British officer Sidney Reilly, who was involved in the Anglo–French plot. I had known Reilly over four months, as from the very beginning of our acquaintance he could bind me to himself. He never talked to me about his political motives, I only knew that he served at the British Legation. He shared a flat with us and when repression against the British officers began, he left us saying he would depart from Russia forever. Shortly before his leave he asked me to do him a favour and pass on to him any letters that may arrive at his former address while he was staying in Moscow. I promised to do that being unaware that these letters may have political meaning, otherwise I would not have agreed to do that, as I had never been involved in politics. At the interrogation I discovered that Reilly had been foully deceiving me for his own political purposes, taking advantage of my exclusively good attitude to him, and by his seeming departure from Moscow he wanted to veil a change of his attitude towards me, intending to move to one divorced lady

34

he had promised to marry.

35

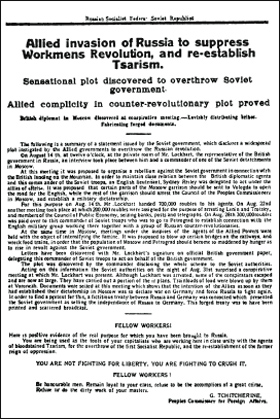

A Russian propaganda leaflet issued to Allied troops in Murmansk, naming Reilly as a conspirator in the plot to ‘overthrow the Russian Revolution’.

Although both statements should be read with a pinch of salt in terms of their exaggerated naïvety concerning Reilly’s actions, they do reflect the genuine shock both women felt on learning of his nefarious and duplicitous exploitation of them on a personal level.

On 3 September, details of the ‘Lockhart Plot’ were sensationally published in the Russian press.

36

Reilly was named as one of the principal plotters and a dragnet was put out for him. The Cheka raided his flat, but once again Reilly had, in the nick of time, vanished into thin air.

EN

F

OR

D

ISTINGUISHED

S

ERVICE

W

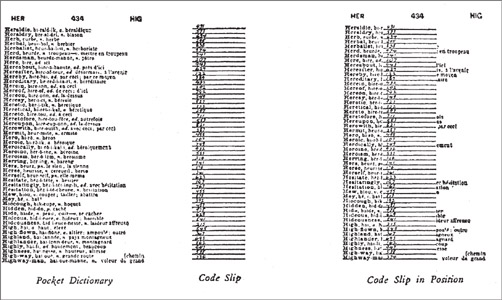

ith Cheka raids taking place throughout Petrograd, Capt. George Hill sent Lockhart a message using SIS ‘dictionary’ code: ‘I have’, he reported, ‘been over the network of our organisation and found everything intact’. ‘There was undoubtedly a fair amount of nervousness among some of the agents’, however.

1

Hill, under the impression that Reilly had been arrested by the Cheka, assured Lockhart that, ‘I have got all of Lt Reilly’s affairs under my control, and provided I can get money it would be possible to carry on’.

2

Lockhart was never to receive the message, for when Hill’s courier arrived at Lockhart’s flat, she found that it had shortly before been raided and Lockhart arrested. The message was therefore diverted to Lockhart’s assistant, Capt. Will Hicks. Hicks replied that it was important to lie low for some days to come, and that to the best of his knowledge there would be no more money for Hill as the source for obtaining it had completely dried up. Hicks too was of the view that Reilly had been arrested, although he had no news to confirm this. On receipt, Hill sent a further message to Gen. Poole informing him of the day’s events in Moscow.

At midday on 4 September, ‘a girl of Lt Reilly’s’ brought Hill a message to say that he was safe in Moscow, having travelled by

train in a first-class compartment from Petrograd. On arrival at the Nicolai Station in Moscow, he had been informed that his chief courier and mistress, Elizaveta Otten, had been arrested. Hill immediately went to see Reilly, who was now in hiding, occupying two rooms in a flat ‘at the back end of town’.

3

When Hill arrived there he found that Reilly had changed his name but was not going out during the day or even at night, as he had no identity papers to match the new name he was using. Reilly wanted a passport, some new clothes and another place to stay, as his present abode was ‘entirely unsuitable’.

4

Although Hill makes no direct reference to whose flat this was, the transcript of the so-called ‘Lockhart Trials’ reveals testimony by Olga Starzhevskaya, who states that Reilly stayed with her between 3 and 4 September, which coincides exactly with the two days he spent at ‘the back end of town’.

5

When Hill proposed that Reilly should make his escape by the safest route, heading westwards via the Ukraine, using a network of agents in that area for safe houses and assistance, Reilly refused. This route, he felt, would take far too long, and instead chose the more dangerous option of travelling north to Finland, from where he hoped to make his way to a neutral port. In the meantime, Hill moved Reilly to new accommodation the following day, 5 September. Intriguingly, although Hill was not specific as to the location, it would seem from his report that this was an office of some description.

6

His dramatised version of these events, published in 1932, however, gives a slightly different account. According to this, Hill lodged Reilly with a prostitute who ‘was in the last stages of the disease which so often curses members of her profession’. Hill claimed that Reilly ‘was the most fastidious of men and while being caught by the Bolsheviks had little terror for him, he could hardly bring himself to spend the night on the couch in her room’.

7

In another clue that suggests that he spent 3 and 4 September with Olga Starzhevskaya, Hill states that Reilly’s change of apartment was a good thing, ‘for the place where he had spent the previous night was raided by the Cheka the next evening’.

8

This would therefore be the night of 5 September, the date of Olga’s arrest. That same evening six or seven of Hill’s couriers were arrested and summarily executed by the Cheka.

The key to the SIS dictionary code used by Reilly and Hill to communicate with each other while in hiding.

As Hill was not suspected of involvement in the Lockhart Plot, Capt. Hicks decided that he should drop his cover of George Bergmann, resume the identity of Capt. George Hill, and leave Russia with the British Mission, who had been given clearance to leave by the Bolshevik authorities. This was most fortuitous for Reilly, for Hill was now able to give him the George Bergmann identity papers that would enable him to make his escape. According to Hill’s report, Reilly left Moscow aboard a sleeper train bound for Petrograd on Sunday 8 September,

9

although Reilly’s own recollection some seven years later was that the date was Wednesday 11 September.

10

Hill’s account, being recorded at the time, is more likely to be the correct one. The date of his departure aside, the chronology of Reilly’s recollections coincide pretty much with accounts given by other participants. Reilly’s account states:

Having finished the liquidation of my affairs in Moscow, on 11 September, I departed for Petrograd in a railway car of the international society in a compartment reserved for the German Embassy, accompanied by one of their legation secretaries and using the passport of a Baltic German. I spent about ten days in Petrograd, hiding in various places, to liquidate my network there and also search for a way to cross the Finnish border – I wanted to escape to Finland. I was not able to do this, so I then decided to go through Revel [now Tallinn]. I departed Petrograd for Kronstadt, after receiving a ‘Protection Certificate’, which was issued to natives of the Baltic. I had, in addition to this document for exiting Petrograd for Kronstadt, a pass issued to one of the Petrograd workers committees in a Russian name. There was a launch with a Finnish captain already waiting for me at Kronstadt, on which I spent the night. I set off for Revel… In Revel I took up residence in the Hotel Petrograd using the name of George Bergmann, an antiquarian who had left Russia after a misunderstanding with the Soviet authorities… After ten days I departed secretly on the launch for Helsingfors, and from there to Stockholm and London, where I arrived on 8 November.

11

Passing through Revel before crossing the Gulf of Finland to Helsingfors was not an option without risk, for Estonia was then under German occupation and the port was a major naval base teeming with officers and ratings of the German Baltic fleet. Fortunately, on disembarking, the Germans found ‘Herr Bergmann’s’ identity papers to be in order and he was able to walk away unhindered. At the hotel in Harju Street he mixed freely with the German officers staying there and dined with them on several occasions, as well as with the captain and his wife.

It was probably with some relief on Reilly’s part that the little boat eventually left Revel for Helsingfors a few days later. On arrival he bade the captain farewell and gave him a sealed, handwritten letter (in German):

I feel that after everything you have done for me, I must not leave you here clothed in all the lies I had to use, and that I owe it to you

to say who I really am. I am neither Bergmann nor an art dealer. I am an English officer, Lt Sidney Reilly, RFC, and have been for about six months on a special mission in Russia, and have been accused by the Bolsheviks of being the military organiser of a great plot in Moscow… I believe it is not necessary to stress that I consider it my duty towards you not to interest myself in anything military here, and not to pump the officers who were introduced to me. I believe that I played the role of the art dealer Herr Bergmann quite well, only once or twice did I catch myself using an English expression; for the rest, I imagine your lady wife was a little suspicious of me! It would be useless to offer you my gratitude – it is too big.

12