Ace of Spies (35 page)

Some weeks later Pepita received a further letter from Boyce in Helsingfors, dated 18 October, in which he broke the news to her that things had definitely gone wrong:

I am on my way to Paris via London and hope to be with you on Thursday or latest Friday. The position I am sorry to say is much worse than I had hoped from the information previously received. It appears that at the last moment just before they hoped to complete the whole business a party of four of them were prospecting in the forests near by and were suddenly attacked by brigands. They put up a fight with the result that two were killed outright. Mutt

5

was seriously wounded and the fourth was taken captive.

6

Promising to meet her in Paris when he would hopefully have more precise and up-to-date news, Boyce signed off. At this point it is clear that Pepita considered the possibility that Boyce might be an OGPU double agent who had entrapped her husband.

7

This would not be the last time that such suspicions were to fall on Boyce.

From the OGPU interrogation records, it would appear that the information Reilly had thus far given about himself was as far as he was willing to go in terms of volunteering the information they were demanding. On 13 October Reilly responded to Styrne's ultimatum, to co-operate fully or face the consequences, by categorically stating, âI am unable to agree'.

8

On 17 October he again wrote to Styrne, emphasising that he would not provide the âdetailed information' they were seeking.

9

Psychological methods were therefore brought to bear on him, which ultimately succeeded in persuading him to co-operate. Even when this point was reached on 30 October, it is clear that Reilly did his best to drag things out.

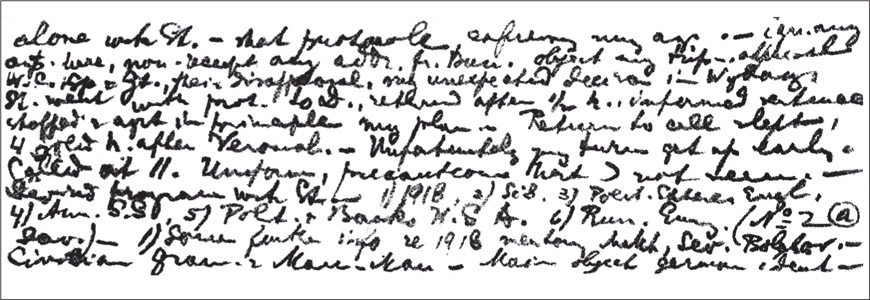

How then was he persuaded to talk and what did he tell them? Reilly himself left a trail of clues in the form of daily notes he made during his last week in cell 73. Using a pencil he made tiny handwritten notes on cigarette papers. These he hid in his

clothing, in his bed and in cracks in the plasterwork of the cell walls. They were later found when the cell was searched, and photographic enhancements made by OGPU technicians.

10

The handwriting in the daily diary is clearly identifiable as Reilly's. The constructions, grammar and use of abbreviations are not only in keeping with his general written style, but are consistent with other examples of earlier diaries he kept.

In 1992 Robin Bruce Lockhart called into question the diary's authenticity in a revised edition of his

Ace of Spies

book,

11

dismissing it as âSoviet disinformation'. If it was an OGPU fabrication, however, created solely to mislead the West, why was it never used at any time during the following sixty-six years of Communist rule in the Soviet Union? On the contrary, it remained classified at the highest level and was kept securely in the archives of the OGPU and its successor organisations.

Why he wrote the diary is another question altogether. The most likely scenario is that he assumed, or at best hoped, that he would eventually be released to the British authorities. Had this happened, he would, no doubt, have tried to smuggle the diary out with him. Like the postcard he posted to Ernest Boyce shortly before his arrest, it was a testament or boast to the fact that he had entered the lion's den and returned to tell the story. It was also a record of OGPU interrogation techniques, which he was sure would be of interest to SIS. The diary itself contains many abbreviations, and the following account reproduces only the text of which the meaning is clear and incontrovertible â

Friday 30 October 1925

12

Additional interrogation in late afternoon. Change into work clothes. All personal clothes taken away. Managed to conceal a second blanket. When called from sleep was ordered to take coat and cap. Room downstairs near bath. Always had premonition about this iron door. Present in the room are Styrne and his colleague, assistant warder, young fellow from Vladimir gubernia, executioner

13

and possibly somebody else. Styrne's colleague in chair. Informed that GPU Collegium

had reconsidered sentence and that unless I agree to co-operate the execution will take place immediately. Said that this does not surprise me, that my decision remains the same and that I am ready to die. Was asked by Styrne whether I wished time for reflection. Answered that this is their affair. They gave me one hour. Taken back to cell by young man and assistant warder. Prayed inwardly for Pita,

14

made small package of my personal things, smoked a couple of cigarettes and after fifteen to twenty minutes said I was ready. Executioner who was outside cell was sent to announce decision. Was kept in cell for full hour. Brought back to the same room. Styrne, his colleague and young fellow. In adjoining room executioner and assistant all heavily armed. Announced again my decision and asked to make written declaration in this spirit that I am glad I can show them how an Englishman and a Christian understands his duty.

15

Refusal. Asked to have things sent to Pita. Refused. They said that no one will ever know about it after my death. Then began lengthy conversation â persuasion â same as usual. After three-quarters of an hour wrangling, a heated conversation for five minutes. Silence, then Styrne and colleague called the executioner and departed. Immediately handcuffed. Kept waiting about five minutes during which distinct loading of weapons in outer rooms and other preparations. Then led out to car. Inside were the executioner, his warder, young fellow, chauffeur and guard. Short drive to garage. During drive soldier squeezed his filthy hand between handcuffs and my wrist. Rain. Drizzle. Very cold. Endless wait in garage courtyard while executioner went into shed â guards filthy talk and jokes. Chauffeur said something wrong with radiator and pottered about. Finally start, short drive and arrival GPU by north â Styrne and colleague â informed post-ponement twenty hours was communicated. Terrible night. Nightmares.

According to OGPU reports, Reilly spent the night alternately crying and praying before a small picture of Pepita. It seemed that the classic âmock execution' technique had finally shaken his resolve. The scenario he describes, the endless waiting, the uncertainty, followed by a postponement of the execution is

typical of this psychological method of interrogation and no doubt induced the nightmares to which he refers.

Much controversy surrounds a letter written on the same date as the âmock execution', 30 October. The full text of the letter, which is contained in the OGPU file on Reilly, is as follows:

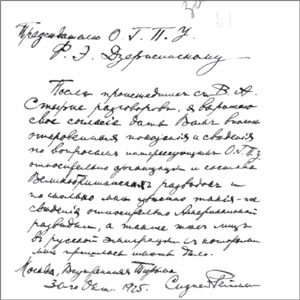

To the Chairman of the OGPU

F.E. Dzerzhinsky

After the discussions that have taken place with V.A. Styrne, I express my agreement to co-operate in sincerely providing full evidence and information answering the questions of interest to the OGPU relating to the organisation and personnel of the British intelligence service and as far as it is known to me what information I have relating to the American intelligence and likewise about those persons in the Russian émigré organisations with whom I had dealings.

Moscow, the Inner Prison,

30 October 1925

[signed] Sidney Reilly

16

Again, there have been suggestions that this too was an âOGPU fabrication'. Gordon Brook Shepherd, for example, asserts that:

⦠it is inconceivable that Reilly, who had throughout displayed defiance, would have failed to mention [in the diary] such a volte-face. It seems all the more probable therefore that the document was produced by the OGPU's diligent factory of lies and forgery to make things look neat and pretty in their files.

17

Edward Gazur, the FBI counter-intelligence officer who debriefed Alexander Orlov after his defection to the US, was even more emphatic: âthere is no doubt in my mind that Orlov did not know of the existence of such a letter when he died in 1973 as he would have certainly addressed the matter with me'.

18

He is firmly of the view that âthe letter was a fabrication conceived and floated by the

KGB [sic]'.

19

Gazur takes his argument further by reasoning that âhad Reilly confessed, he would have likewise been placed on trial if only for the Soviets to reap an extraordinarily bountiful harvest of propaganda'.

20

On 30 October 1925, Reilly wrote to Cheka boss Felix Dzerzhinsky, in a last ditch effort to buy himself more time.

This scenario is a most unlikely one, however. There is no evidence that the Bolsheviks ever had any intention of subjecting Reilly to a show trail. Not only had he already been tried

in absentia

in 1918, and been sentenced to death, they had already announced his death via the Moscow Trust Council meeting within days of his arrest. Clearly, they would have found it a little difficult to then bring him back to life in order to place him on trial. Furthermore, Reilly's letter can in no way be described as a âconfession'. It is purely a statement of intention that he is prepared to co-operate. Savinkov, on the other hand, certainly did âconfess' in every sense of the word, and the statement he made was a clear recanting of his opposition to the Bolsheviks:

I unconditionally recognise your right to govern Russia. I do not ask your mercy. I ask only to let your revolutionary conscience judge a man who has never sought anything for himself and who has devoted his whole life to the cause of the Russian people.

.21

Reilly, on the other hand, no doubt hoped that the letter would save his life or at least buy him time. In fact, his own handwritten notes testify to the fact that during the following five days he did exactly what he said he would do in the

Dzerzhinsky

letter. It is also clear, however, that what he told them was generally low-grade information, much of which they already knew. The one thing they were keen to learn more about, the identity of SIS agents currently working in Russia, he was unable to tell them, as he had had no connection with SIS for over four years.

Saturday 31 October 1925

Next morning called at 11. Spend day in Room 176 with Sergei Ivanovich and Dr Kushner.

22

Apparently Styrne much impressed with his report â increased attention. At 8 p.m. drive dressed in GPU uniform. Walk in country at night. â Arrival Moscow apartment. Great spread. Tea. Ibrahim. Then conversation alone with Styrne â that protocole [sic] expressing my agreement. Ignorance of any agents here â object my trip. Appraisal of Winston Churchill and Spears. My unexpected decision in Wyborg. Styrne went with protocol to Dzerzhinsky, returned half an hour later. Informed sentence stopped and agreed in principle my plan. Return to cell slept, four solid hours, after Veronal.

23

â Unfortunately my turn get up early. â Called at 11. Uniform, precautions that I not be seen. Devised programme with Styrne â 1) 1918, 2) SIS, 3) Political spheres England, 4) American Secret Service, 5) Politics and banks USA, 6) Russian émigré Source for information regarding 1918 â Main object German identification, scene at American Consulate

24

â Cut off supplies untruth

25

â Accused of provocation â 2a) Savinkov's changed attitude, distrust, my conviction proven. My intentions if Savinkov returned. Rest. Ask whether knew Stark,

26

Kurtz.

27

Story of Operput,

28

Yakushev.

29

Then

began on Number 2 â SIS. Only introduction. â finished 5 p.m. Retired to room 176. Rest, dinner. At 7 p.m. dictated Numbers 4 and 5. Then cell. Veronal did not act.

The last week of Reilly's life is recorded in the diary he wrote on cigarette papers in cell 73.

Sunday 1 November 1925

During interrogation tremendous stress laid whether Hodgson

30

has any agents and whether any inside agents anywhere in Comintern. â Questions regards Dukes,

31

Kurtz, Lifland, Peshkov.

32

â Questions regarding Litseintsy.

33

Told story of Gniloryboff

34

and other case attempted escape. Asked whether any agents are in Petrograd. Lots of talk about my wife â offers any money or position â Sergei Ivanovich Kheidulin.

35

Feduleev

36

and guard with glasses was with me in cell. No work. Drive in afternoon. Corrected American report.