Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation (9 page)

Read Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation Online

Authors: Mark Pelling

Tags: #Development Studies

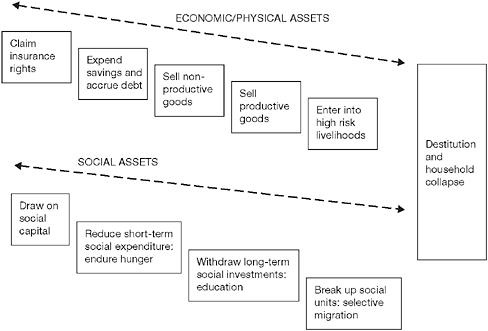

Figure 2.2

The coping cascade: coping and erosion of household sustainability

(Source: based on Pelling, 2009)

example, child sharing is a well-developed coping mechanism in the Caribbean that need not signify approaching household collapse. Here the extended family, not the household, is the basic unit of social organisation (Pelling, 2003b). Broadly, though, as a household approaches collapse subsequent acts are more difficult to reverse.

The delicate balance between the terms coping and climate change adaptation (see

Table 2.2

), and the negotiation of the intellectual division of labour between them can be found in some early writing on adaptation. Kelly and Adger (2000) define coping capacity as the ability of a unit to respond to an occurrence of harm and to avoid its potential impacts, and adaptive capacity as the ability of a unit to gradually transform its structure, functioning or organisation to survive under hazards threatening its existence. This distinction builds on earlier work; for example, working on food security, Gore (1992, in Davies, 1993) offers a distinction based on the actor–institution relationships. Coping is the means to survive within the prevailing systems of rules; adaptation is indicated when institutions (cultural norms, laws, routine behaviour) and livelihoods change. This distinction is becoming increasingly accepted. Under this rubric an example of coping might be selling cattle during drought, with adaptation signified by migration or a change in livelihood to supplement or replace dependence on livestock. Critics of this division argue that, on the ground, the distinction between coping and adaptation in terms of the depth of consequence for actors is

Table 2.2

Distinctions between coping and adaptation

Coping | Adaptation | Source |

The ability of a unit to respond to an occurrence of harm and to avoid its potential impacts | The ability of a unit to gradually transform its structure, functioning or organisation to survive under hazards threatening its existence | Kelly and Adger (2000) |

The means to survive within the prevailing systems of rules | Change to the institutions (cultural norms, laws, routine behaviour) embodied in livelihoods | Gore (1992) |

The range of actions available to respond to the perceived climate change risks in any given policy context | Change to the set of available inputs that determine coping capacity | Yohe and Tol (2002) |

The process through which established practices and underlying institutions are marshalled when confronted by the impacts of climate change | The process through which an actor is able to reflect upon and enact change in those practices and underlying institutions that generate root and proximate causes of risk, frame capacity to cope and further rounds of adaptation to climate change | Pelling (2010) |

greatly influenced by the viewpoint of the observer. This blurs the practical utility of the empirical boundaries between coping and adaptation, producing a potential lack of analytical and policy clarity (for example, Saldaña-Zorrilla, 2008).

Yohe and Tol (2002) offer a nuance on the distinction between coping and adaptation described above. They see adaptive capacity as describing the set of available inputs that determine coping capacity which itself is manifest in the range of actions available to responding to perceived climate change risks in any given policy context. Adaptive capacity is determined by underlying social factors: resources, institutions, social capital, human capital, risk spreading, information management and awareness. Their availability is context specific and path dependent. Coping capacity is defined by the range of practical measures that can be taken to reduce risk. The range, feasibility and efficiency of these measures is determined by adaptive capacity. This logic reveals some insightful outcomes in the relationships between inputs and actions (adaptation and coping). Enhanced investment in the ‘weakest link’ component of adaptive capacity has the

advantage of raising coping capacity across the board – or at least until the next weakest link emerges to limit coping. By the same token investing in one component in isolation need not increase coping capacity. Adding to the resource base may, for example, have no effect on coping capacity if institutional processes or decision-making structures block implementation.

The distinction being made by these authors reflects other attempts to disentangle distinct relationships between actors and their environment. This helps provide some depth to the more narrowly focused challenge of coping/adaptation in climate change. The interest of Freire (1969) was to make transparent the potential role of education in society – much like the climate change problem, his concern was to see development as a process that contained what the poor knew and what they imagined they could do with knowledge. The distinction between ‘adapted man’ (that is, someone who has learnt to live with the current system) and ‘critical consciousness’ has parallels with coping and adaptation. Adapted man corresponds with coping – where successive rounds of coping, that is, of accommodating one’s life to live with hazard, describe well the ratchet effect undermining assets and human wellbeing. Critical consciousness – the ability to see one’s position in society as a function of social structures as a prerequisite to seeking ways of making change in those structures – has great parallels with the institutional dimensions of adaptation described above. The difference is that climate change has to date been driven predominantly by a concern for maintaining efficiency in the output of economic systems and livelihoods rather than in the balance of power between actors or as embodied in institutions. Thus the current modes of defining adaptation go only halfway to meet Freire; they acknowledge the action to change institutions but do not emphasise the potential for emancipation that this could bring – nor indeed that this could be a parallel and even motivating goal for climate change adaptation.

The systems worldview that has had a great influence on recent thinking about human responses to climate change also recognises the potential for more profound change (for example, Flood and Romm, 1996; Pelling

et al.

, 2007b). Argyris and Schön (1996) identified three kinds of learning, termed first, second and third loop learning. Only the first two are encompassed routinely in the distinction between coping and adaptation in climate change literature. First loop learning corresponds with coping – learning to improve what you already do. Second loop learning corresponds with adaptation – learning to change the mechanisms used to meet your goals. Third loop learning – learning that results from a change in the underlying values that determine goals and actions – is less clearly expressed within current adaptation theory.

The lack of emphasis in climate change literature on adaptation as critical consciousness or third loop learning is likely a reflection on the difficulty of making clear empirical associations between climate change related impacts and social change of this order. Chapters

5

and

8

aim to provide one step forward in opening this discussion. There is also the possibility that the climate change community – which has its eyes tightly focused on the IPCC process, and which in turn is a product of negotiated content between science and governments – has

not found analysis of power as part of adaptation to be a priority. It risks alienating the political and technical decision-makers for whom the IPCC endeavour is designed to support.

Another area where coping is still a predominant term, and one where further development could prove insightful for work on climate change, is the psychological literature. This work views coping as an interior action determined by the interaction of cognitive and emotional process, but acknowledging interaction with socialised values, access to information and social–historical context. Individual ability to cope with stress associated with catastrophe has been described as psychological resilience (Walsh, 2002). This literature is most developed in the USA, with Hurricane Katrina stimulating many studies including Lee

et al.

(2009) who identified psychological resilience as an outcome of survivors’ perseverance, ability to work through emerging difficulties and ability to maintain an optimistic view of recovery. Amongst this group those who suffered human loss were least able to cope, with property loss having only a minor impact on capacity for psychological recovery. Other hurricane events in the US have shown that survivors who reported more resource loss also reported higher levels of active and risk-reducing behaviour (Benight

et al.

, 1999). This has important implications for the appropriateness of mainstream methodologies for measuring disaster impact and for disaster response and recovery efforts which predominantly focus on economic and physical rather than social and psychological aspects.

Psychology has begun to offer some insight into the factors leading to individual wellbeing and empowerment post-disaster, although the link to material coping actions is as yet less well defined. Psychological traits associated with coping following Hurricane Katrina included a heightened sense of control over one’s destiny and of personal growth. These in turn were attributed to survivors who were problem-focused, accepting of loss, optimistic and held a religious worldview (Linley and Joseph, 2004). In the general population talking, staying informed and praying enabled coping, emerging as predictors of decreased psychological stress during post-disaster relocation (Spence

et al.

, 2007), with spirituality particularly significant for older African American Katrina evacuees (Lawson and Thomas, 2007). In a comparison of psychological resilience pre-and post-Katrina, Kessler

et al.

(2006) found reduced thoughts of suicide after the disaster in survivors expressing faith in their ability to rebuild their life and a realisation of inner strength. This is important in providing an empirical link for adaptation, between internal processes of belief, identity and self-worth and external actions, in this sad case illustrated through suicide rates. Outside the US, following the 2003 earthquake in Guatemala, feelings of self-control and self-assurance were also found associated with adaptation outcomes of ‘successful survivors’ who reconceptualised the crises as opportunities for acquiring new skills (Vazquez

et al.

, 2005). This work provides one approach for promoting a progressive response to climate change through acknowledging the interplay of social and psychological root causes (Moos, 2002), but this has yet to be systematically applied (Zamani

et al.

, 2006). It provides an initial evidence base

to begin a characterisation of specific psychological orientations associated with adaptation and linking interior and exterior expressions of adaptation, taking us closer to gaining some leverage on the ways in which individuals and social collectives might move between different cognitive, emotional and potentially intellectual states; the latter opening scope for the study of shifts between ‘adaptive man’ and critical consciousness or first, second and third loop learning.

In order to incorporate deeper levels of change while retaining close links to the existing literature adaptation to climate change is defined here as: The process through which an actor is able to reflect upon and enact change in root and proximate causes of risk.

This formulation sees coping as the range of actions currently being enacted in response to a specific hazard context. These are made possible by existing coping capacity (which may extend beyond the range of coping acts observed at any one time). Adaptation describes the process of reflection and potentially of material change in the structures, values and behaviours that constrain coping capacity and its translation into action. Coping then is an expression of past rounds of adaptation. Both adaptation and coping will unfold simultaneously and continuously in shaping human–environment relations, they will interact and on the ground they may be hard to separate as reflection and application occur hand-in-hand. Still, from an analytical perspective and for policy formulation there is a value in distinguishing these two components of human–environment relations.

The coproduction of vulnerability/security by coping and adaptation brings the possibility that adapting to climate change can undermine as well as strengthen capacities and actions directed at coping with contemporary climate related risks. Coping may be limited for longer-term gain or a result of ignorance or injustice in the implementation of adaptation. This can be seen in the loss of income accepted by low-income families who are able to provide an education for their children. This is an adaptive action that constrains contemporary coping capacity, but with the aim of providing future gains that will provide the means for better family wellbeing including capacity to cope with uncertainty and shocks associated with the climate change. More likely, the immediacy of political life will produce a tendency for coping that distracts from or undermines the critical reflection and long-term view of adaptation. The danger is that coping is felt to be sufficient so that the potentially difficult questions and changes in development that adaptation might bring are temporarily evaded. At the scale of large social systems, this tension is illustrated by the trade-off between short-term social disruption and the long-term easing of socio-ecological friction proposed by Handmer and Dovers (1996) (see below).