Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation (11 page)

Read Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation Online

Authors: Mark Pelling

Tags: #Development Studies

Social systems displaying openness and adaptability tackle the root causes of risk, are flexible and prepared to change direction rather than resist change in the face of uncertainty. That this mode of resilience is so rare is testament to the huge inertia the results from personal and collective investment in the status quo. Large fixed capital investments make change difficult as do investments in soft infrastructure – preferences for certain types of education or cultural values making shifts painful in industrial societies. Dangers also lie with this form of resilience: instability will lead to some ineffective decisions and maladaptation would need to be prepared for within individual sectors as a cost of wider systems flexibility. These are both worries that decision-makers have cited in making it difficult for them to commit to adaptive management strategies, as described above.

Handmer and Dovers prefigure their account by a caution that while the three classifications are designed to cover the full range of policy responses to the adaptation challenge, most actors will operate in only a small part of this range. This points to a central dilemma for progressive adaptation – that the comfort zone for adaptive action is relatively small because both those with power and the marginalised are wary of the instability they fear from significant social change (see

Chapter 5

). Resilience then has the possibility of both identifying the scope for flexibility within the socially accepted bounds of stability but also making transparent for all social observers the range of choices foregone. Mapping the characteristics of social systems that are more or less amenable to these three forms of resilience is a key foundation for the analytical framework development in this book which places emphasis on the processes through which systems undertake or resist adaptive change.

More contemporary work on resilience and its relationships with vulnerability and adaptation have also applied critical reasoning. This has focused on the advantages of inclusive governance. This, it is argued, facilitates better flexibility and provides additional benefit from the decentralisation of power. On the down side, greater participation can lead to loose institutional arrangements that may be captured and distorted by existing vested interests (Adger

et al.

, 2005b; Plummer and Armitage, 2007). Still, the balance of argument (and existing centrality of institutional arrangements) calls for a greater emphasis to be placed on the inclusion of local and lay voices and of diverse stakeholders in shaping agendas for resilience through adaptation and adaptive management (Nelson

et al.

, 2007). This is needed both to raise the political and policy profile of our current sustainability crisis and to search for fair and legitimate responses. Greater inclusiveness in decision-making can help to add richness and value to governance systems in contrast to the current dominant approaches which tend to emphasise management control. When inevitable failures occur and disasters materialise this approach risks the undermining of legitimacy and public engagement in collective efforts to change practices and reduce risk. This takes us back to Handmer and Dovers’ (1996) analysis of the problem of resilience and shows just how little distance has been travelled in the intervening years.

Acts of adaptation are stimulated by the crossing of risk, hazard and/or vulnerability thresholds. Each threshold is socially constructed, a product of intervening properties including identification, information and communication systems, political and cultural context and the relative, perceived importance of other risks, hazards and vulnerabilities that compete for attention. The existence of social thresholds explains the ‘lumpiness’ of human experience, where history does not unfold as a gradual story but in fits and starts. Forward looking adaptation, or the impacts of climate change resulting from a lack of sufficient adaptation, may be catalysts for the breaching of thresholds.

Risk is ever present in society. The level of risk that is accepted by different social actors determines the first threshold (see discussion on coping) and is shaped by whose values and visions for the future count in society (Adger

et al.

, 2009a). For any social group the level of acceptable risk can change as scientific innovation, media interest and public education influence awareness amongst the public and decision-makers. Communication between science, decision-makers, the media and the public is determined by norms of trust. Trust is built over time by the everyday performance of scientific or government bodies but is easy to lose (Slovic, 1999). Where there is a confidence gap in advisory bodies, the government or science, popular regard for new risk announcements will be greeted with scepticism (Kasperson

et al.

, 2005), with a preference for self-reliance or fatalism amongst those at risk and potentially resistance to any coordinated adaptation. It is here that dedicated intermediary organisations or individuals that can translate climate science into the language of target audiences (such as agricultural extension agencies) play a significant role in shaping people’s willingness to reduce risk (Huq, 2008). Indeed part of the challenge facing adaptation to climate change is the need to communicate without confusing, and the science community that has championed climate change research thus far has not found this easy (Hulme, 2009).

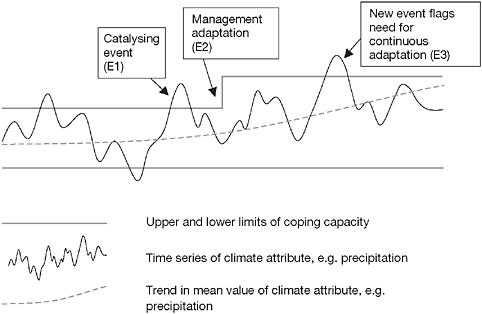

Climate change is felt locally through many environmental indicators.

Figure 2.3

represents how just one – say precipitation – is influenced by climate change and how this is related to the timing and scope of coping and adaptation. In this case climate change produces reduced hazardousness at minimum extremes (drought) but increased hazardousness at maximum values (flood). In this way

new hazard thresholds challenge existing hazard management strategies which are breached until the changing hazard threshold is recognised (E1) and responded to (E2). The distance between these two points reflects the risk acceptance and communication thresholds described above. A final threshold that determines adaptation comes from changing vulnerability profiles.

Demographic and economic change in particular influence the likelihood of adaptation. This is often not integrated into accounts of adaptive capacity and action (see

Figure 2.3

) but is particularly important in rapidly changing contexts such as rapid urbanisation, economic restructuring or where social tensions might lead to armed violence. The vulnerability threshold suggests there is a critical mass of assets or people at risk and of risk management capacity that are needed for adaptation to be likely. This also has consequences for the kind of adaptation undertaken. Thus a small coastal settlement may undertake independent, spontaneous adaptations to protect livelihoods in the face of sea level rise, but should this area be subject to investment by the corporate tourism sector and subsequent high levels of labour in-migration adaptation may become more coordinated, collective and planned.

Figure 2.3

, although stylised, is useful in demonstrating several other attributes of adaptation (Füssel, 2007). It shows the disproportionate ability of extreme over average climatic conditions to stimulate adaptation, the need to consider natural climatic variability and anthropocentric climate change together in planning adaptations, and the continuous process of review and response needed of adaptation to climate change as hazard thresholds change (E3). The fuzzyness inherent

Figure 2.3

Adaptation thresholds

(Source: based on Füssel, 2007)

in labelling adaptation as reactive or proactive is revealed with the decision to adapt being both a reaction to the preceding extreme event and a proactive anticipation of future risk. A reactive motivation can lead to a proactive adaptation. This said, the time needed to make decisions to adapt to climate change and complete adaptive measures such as major infrastructure works or the reform of housing stock is often several years if not decades so that incremental adaptation may be dangerous and costly (Reeder

et al.

, 2009). In contrast, planning over extended timeframes opens decision-making to uncertainty. As the limits of scientific knowledge are reached so decisions are based increasingly on value judgements. These in turn are shaped by the structures and norms of governance systems and cultural–historical expressions of acceptable risk that inform and legitimate adaptation (Paavola and Adger, 2006). Ultimately this directs scrutiny to questions about who it is that determines the principles upon which adaptive choices are made as much as the nature of the decisions themselves.

There are two bases for evaluating between adaptive choices: economic costs and human rights. At the global scale both approaches have already been used to argue for mitigation (Stern, 2006). Lack of agreement on global responsibilities for the distribution of costs of adaptation (which have not been fully calculated but likely far outweigh those of mitigation) mean the case for adaptation has been less forcefully argued using either approach, although human rights has been used to frame accounts of climate change impacts as unjust, for example by the UN Human Rights Commission in its resolution 7/23 (UN Human Rights Commission, 2009).

At the regional level and within countries there is some experience in the use of cost–benefit analysis (CBA) as a tool for adaptation decision-making (Splash, 2007). CBA tries to establish the costs of alternative adaptive measures and how much damage can be averted by increasing the adaptation effort given a specific climate change scenario. CBA works for individual sectors where costs and benefits can be derived from market prices; it is harder when multiple sectors are included and when market prices are unavailable – for example, in placing a value on human health or wellbeing – and where the items being compared are incommensurable (Adger

et al.

, 2009c). Despite such limitations, some sophisticated methods are emerging which can at least show clearly what is known and provide a logical framework for political judgement. For example, it has been suggested that the range of choices for adapting to heat stress in the UK (though not their social and environmental costs, including potential for maladaptation) is likely to be maximised in future global contexts characterised by active free markets and entrepreneurialism, but more limited if strong environmental regulation becomes the norm (Boyd and Hunt, 2006). CBA has also been used effectively to argue for proactive adaptation through investment in disaster risk reduction as an alternative to managing disaster risk through emergency response

and reconstruction. The World Bank and US Geological Survey calculate that an investment in risk management of US$40 billion could have prevented US$280 billion in losses during the 1990s alone, a CBA ratio of 7:1. In high risk locations advantages of proactive risk reduction are even higher, Oxfam calculates that construction of flood shelters costing US$4,300 saved as much as US$75,000 a ration of 17:1 (DFID, 2004a). These are compelling ratios but do not allow estimation of costs for specific investments before disaster strikes and in this respect their weight in decision-making is limited.

Given the methodological constraints on economic assessment for the costs and benefits of adaptation options can ethics help? Caney (2006) argues that people have a moral right not to suffer from the adverse effects of climate change. However, a central dilemma for investing in adaptation based on human rights when resources are scare is whose rights to prioritise. What is the basis on which to decide? Is it fairer to target interventions to reduce risk of climate change impacts and aid adaptation amongst the most vulnerable (as Rawls would argue), or aim to generate the maximum collective good (following the utilitarian philosophy of Bentham). The latter approach may well target those who are only marginally vulnerable. It is justified by the assumption that the overall increase in wellbeing would provide a resource for compensating those negatively impacted by this decision. The utilitarian approach is one origin of economic cost–benefit analysis.

There are many strands to systematic thinking on justice that could inform decision-making for adaptation. The dominance of OECD countries in international policy and the academic literature positions the Western philosophical tradition closer to the existing intellectual core, and the relative potency of justice arguments thus framed. This is not to deny that non-Western philosophies, many perhaps not formalised, will shape local decisions and actions. Indeed their interaction with top-down policy based on Western ideas of justice may be a source of tension or misunderstandings. There are also inspiring and profound differences that can inform questions of sustainability and adaptation from non-Western sources. For example, the Buddhist aim to decrease suffering (including unmet desires) through individual control of the birth of desires (Kolm, 1996) presents a radical departure from dominant Western logics which aim to address perceived need not through individual self-knowledge, chosen restraint and a revelation of happiness, but through the social rights of access, distribution and procedure; or worse through imposed coping and restraint in the worst forms of adaptation. Meeting these Western elements of justice has further been constrained by a framing of the solution in dominant liberal political-economies that assumes needs must be met through increasing material wealth and energy consumption – an error identified by many Green philosophers and lying at the heart of Norgaard’s (1995) observation of the lack of sustainability and risk produced by humanity’s dangerous coevolution with hydrocarbons.