Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation (14 page)

Read Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation Online

Authors: Mark Pelling

Tags: #Development Studies

Self-organisation can evolve slowly in response to changing social values and organisational forms driven by demographic shifts or changes in popular ideology, but also more rapidly. This latter opportunity has been observed following disaster events when new forms of social organisation emerge as dominant forms fail (Pelling and Dill, 2009). Emergent organisation ranges from spontaneous solidarity as neighbours undertake first response, to coordinated networks of NGOs and state agencies in recovery (see Chapters

5

and

8

). Capacity to self-organise, like social capital, is particularly difficult to measure in society for this reason – much capacity is hidden and latent, its emergence dependent upon wider social and political context and the nature of threats and opportunities presented to society. It is not possible to measure capacity for self-organisation from existing organisational forms alone. Berkes (2007) notes that because social capital can remain latent in society, social relations that might have been used in the past can be reinvigorated as new threats or needs arise. This was the case in Trinidad and Tobago when networks originally established to deal with coral reef management in Trinidad and Tobago have also played a key role in disaster preparedness (Adger

et al.

, 2005b). Existing organisational forms can also serve to hinder the emergence of novel self-organisation through institutional inertia so that observed high levels of organisation may not alone indicate high levels of capacity for self-organisation to respond to future climate-change-related pressures.

Social learning and self-organisation reinforce each other so that a social system exhibiting rich capacity for social learning is also likely to have considerable

scope for self-organisation. The extent to which social learning can be fixed through self-organisation is tracked through three elements of capacity to change: consciousness, institutionalisation and implementation. Consciousness is the capacity to reflect on the outcomes of and alternatives to established norms and practices and sets the limits for subsequent alternative visions or discourses. Bateson (1972) described this as dutero-learning – making learning to learn an act of adaptation. There is no normative assumption on the scope or depth of learning so that this can include adaptive ingenuity and critical consciousness. Institutionalisation is the capacity to move from recognition of constraints to affect change in the institutional architecture that frames implementation through the reproduction of existing, or insertion of new, values and practices. All three processes can unfold within the canonical and shadow systems. Their interaction provides reinforcing or contradictory realms for experimentation and learning and for novel values and practices to emerge (Pelling

et al.

, 2007).

Organisations operate at scales from the household to firms and national and international bodies. They are often seen as agents in the construction of adaptation for subsidiary actors – for example, by enforcing environmental management regimes or regulating land markets – but in this and the subsequent chapters we also focus on the ways in which internal social relations shape information flow, agency and the direction an organisation can take in adapting itself to a changing external environment. An important distinction is to be made between organisations and institutions.

Following North (1990), institutions are defined as the rules of the game (formal and informal) that influence adaptive behaviour. Organisations are the collective units, embodying institutions, that are vehicles for adaptation. Organisations are not monolithic; they contain potentially competing agents and interests so that internal adaptive change brings new risks as well as opportunities which are not experienced evenly within organisations even when the stated focus of change is on the external environment. Internal differentiation also means that adaptations undertaken by individuals are not always replicated throughout the organisation with consequences for efficiency as well as equity in adaptation. This is the case for households, firms and public or civil society organisations alike.

If organisations and individuals or social groups within them can learn, how might learning be observed? At a surface level, learning is observed through changes in behaviour (signifying implementation and assuming consciousness and institutionalisation). In addition to this behaviouralist Gross (1996) focuses on externally validated, physical behaviour, and following Maturana and Varela (1992) and Ison

et al.

(2000), internal actions are also interpreted as learning. That is, we can learn in relation to different modes of interacting with the world: emotional and conceptual as well as physical. Our learning corresponds to differences in the way that we act (consciously or unconsciously) within these modes, which in turn arise in response to our ongoing experience. The judgement

of what constitutes behaviour lies with the observer in question, but the definition does not rule out internal and tacit activities such as conscious or unconscious cognition, emotional affect or the formation and operation of personal relationships, for example. Identifying different realms of behaviour is important in sharpening our focus on the site(s) where adaptation can be observed; not only in material actions, but in contrasting attitudes or views that have not been allowed translation into action. In this way Pred and Watts (1992) identify the behaviour of marginalised actors who need to keep low visibility in the face of surveillance by more powerful actors, and the potential importance of private language as a mechanism for resistance that could form a potential resource for adaptation when organisational relationships or external contexts change.

Constructing the learner as an individual or social entity links individual learning to social processes of change that emerge at the collective level. Thus social adaptation can be seen as collective learning. This is not a claim that individual and collective behaviour are qualitatively the same, but recognises the interaction of learning and adaptive behaviour at these different levels. In this way, adaptation to climate change and variability can be read at different levels of learning operating as a range of system-hierarchic scales – the behaviours of components and subsystems of the system, as well as changes to the emergent properties of the system – and this can be used to unpack different adaptive trajectories: international, national, local. It may be that adaptive behaviour emerging at one scale – say the local – is the result of learning that has been ongoing amongst a range of actors networked across a range of scales. Additionally, adaptation at one spatial (or temporal) scale can impose externalities or constrain adaptive capacity at other scales. In short, the system-hierarchic scale where adaptation is or is not enacted is a socio-political construction (Adger

et al.

, 2005a).

Organisations are spaces of engagement where learning and adaptive capacity can be constrained as well as enhanced (Tompkins

et al.

, 2002). A useful distinction is between organisations and communities of relationships acting within or across them in supporting, antagonistic or ambivalent ways. Communities describe those collectives through which close relationships reinforce shared values and practices; although reinforcement may not necessarily contribute to the organisation’s (or even the community’s) adaptive capacity, it can lead to closed thinking and the suppression of questioning established norms – a property referred to as groupthink by Janis (1989). In a less formal context a similar phenomenon is described by Abrahamson

et al.

(2009) who observed how closed social networks amongst the elderly led to the self-reinforcing of myths of personal security regarding vulnerability to heatwaves in the UK as new information or ideas were treated with caution.

For Wenger, learning in a community arises through participation and reification, the dual modes through which meaning is socially negotiated. Participation refers to ‘the process of taking part and also to the relations with others that reflect this process. It suggests both action and connection’ (Wenger, 2000:55). Participation is thus an active social process, referring to the mutual engagement of actors in social communities, and the recognition of the self in the other.

Reification is the process by which ‘we project our meanings into the world, and then we perceive them as existing in the world, as having a reality of their own’ (Ibid., 58). Thus reification can refer to the social construction of intangible concepts as well as the meanings that members of a community of practice see embedded in physical objects.

Communities of practice are often not officially recognised by the organisations they permeate (Brown and Duguid, 1991). Their official invisibility in the shadow system can be thought of as being made up of constellations of communities of practice held together by bridging ties of social capital. The link between communities of practice, informal networks and unofficial activity in organisational settings is an important association to make in tracing the workings of the shadow system in building adaptive capacity. Wenger (2000) uses the language of social capital to help define the characteristics of individual communities of practice, which, he argues, can be defined by a shared identity and held together by bonding capital. The influence of personality traits and the role of personal and professional sources of trust in bridging across communities within the public sector are discussed by Williams (2002). It is the quality, quantity and aims of individuals connected together in communities of practice, and their linking of boundary people and objects, that determine the influence of the shadow system on adaptive capacity.

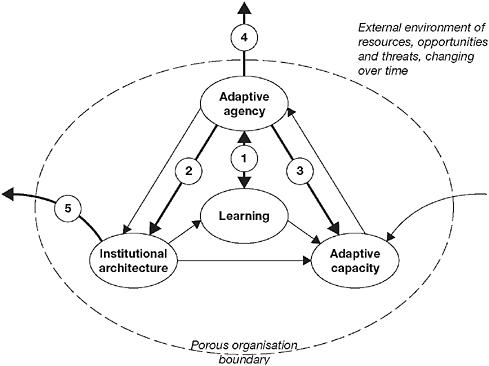

Figure 3.1

summarises the preceding discussion by identifying five pathways through which adaptive action can be undertaken by individuals or discrete subgroups within an organisation. These actions are a consequence of interactions with the institutional architecture, adaptive capacity and facility for learning held by an organisation. The host organisation can be any collective social unit, from a legally mandated government department or agency to more flexible but nonetheless restrictive private sector organisations or loose associations of actors from civil society in organised networks.

Feint arrows indicate the direction of conditioning between these aspects of organisational life, such that the institutional architecture conditions the type and scope of learning and adaptive capacity (either directly or through prescribed forms of learning) and adaptive agency through the setting and policing of formal objectives, structures and guidelines for practice in the organisation. Adaptive capacity conditions adaptive actions by setting constraints on what can be thought and done as well as the goodness of fit of existing resources to the identified external pressure. The organisation draws resources, opportunities and threats from the external environment and exerts adaptive actions upon it.

Only two of the five forms of adaptation are visible from outside the organisation. This not only flags the need to examine interior life of organisations but also the overlapping of resilience, transition and transformation with the latter two modes of adaptation potentially being found operating inside an organisation which itself applies only resilience to the external world; indeed transition or

transformation might be necessary internal motors for external resilience (see

Figure 3.1

).

The five adaptive pathways are characterised in

Table 3.1

. Adaptive agency refers to that held by individuals, sub-divisions or cross-cutting communities of practice below the level of the organisation. Such agency is made reflexive through learning (pathway 1) which is itself an adaptive act. Reflexivity implies strategic decision-making (of an entrepreneurial individual, advocacy coalition and so on within the organisation). This can be focused on symptoms leading to adaptive ingenuity, or consider root causes indicating to critical reasoning. Learning through critical reasoning or adaptive ingenuity can lead to lobbying for change in the institutional architecture of the organisation (2). This can in turn force reconsideration of aims and behaviour informing the selection and use of resources that form adaptive capacity (3) (a key concern given a dynamic external environment). Feedback from capacity and institutional architecture then potentially reshapes adaptive agency.

One important message from this approach to adaptation is that only two modes of adaptation are observable from outside the organisation. These are efforts to shape the relationship between the organisation and operating environment made either by the agent (4) or organisation (5). This is a strong argument for studies of adaptation to climate change to extend their analysis from the external/public to more internal and private life of organisations of all kinds. The

Figure 3.1

Adaptation pathways within an organisation