After Tamerlane (57 page)

Authors: John Darwin

Of all the great powers, Russian had been the least well equipped for a total war. It lacked the industrial strength to sustain its vast armies. It needed the help of its Western allies. But there lay the problem. With the Straits closed by Turkey, the only accessible ports through which aid could be sent were Archangel in the far north and Vladivostok in the far east, both far from ideal. Much of it piled up uselessly. Even if more had been sent, it is doubtful whether it would have made any difference. Russia's railway system could not cope with the strain of supplying the fronts, or transporting the food and fuel that were needed to keep its war economy going. In all the countries at war, the combination of hardship, anxiety and dissatisfaction with leaders who failed to bring victory created political tension. Russia's military failure â its huge losses of manpower, the vast loss of territory â was overwhelming. The desperate shortages in the main industrial cities â above all in Petrograd, the imperial capital â destroyed civilian morale and factory discipline. Setbacks on this scale would have shaken any government. But the tsarist regime was uniquely vulnerable. It had no political leader to direct the government with any shred of claim to popular backing. Its ministers were bureaucrats, answerable to the tsar, as much each other's rivals as political colleagues. The elected Duma could denounce and abuse, but had no power to remove them. The tsarist court was widely suspected of harbouring defeatists or traitors. As discontent mounted, the only available recourse was repression. The tsar's authority rested on police control of the crowd and (ultimately) the loyalty of the army. In the spring of 1917, amid a wave of popular disturbance in Petrograd, both broke down. It took barely a week to force the tsar's abdication and the end of a monarchy that was a thousand years old. The rising, remarked an English historian who spent the war in Russia, âhad been unorganized and elemental. It was if a corpse had lain on top of a passive people till with a single push from below it had rolled away of itself.'

7

It seemed at first as if the new Russian state, with leaders answerable to the Duma, would have the patriotic drive, the public support and the political energy to rekindle the war effort and resume the offensive. But Russia's war economy was too badly damaged, and the organized discontent of the industrial workforce too deeply rooted, for any quick recovery. Perhaps only a German collapse could have saved the post-tsarist liberal state. After little more than six months it faced the same combination of popular discontent, economic disaster and military failure, but without the machine of repression on which the tsars had relied. Peasant hardship and land hunger dissolved the old rural order as the gentry were forced out (or murdered) and their estates divided up. (By 1914, peasant communities or individuals already owned three-quarters of arable land, and the consolidation of property in the hands of richer peasants may have sharpened the sense of land shortage.)

8

The Bolshevik coup in October 1917 brought to power a revolutionary government who knew that their own survival meant Russia's leaving the war. Indeed, it was their promise of peace and their apparent support for the peasants' revolt that ensured a precarious triumph in the struggle for power.

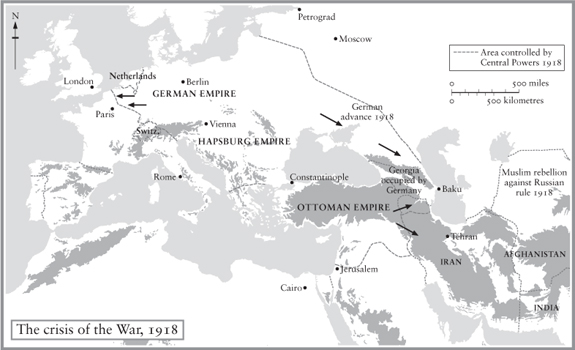

The price was paid in March 1918 at the town of Brest-Litovsk, where the peace treaty was signed. To buy peace from the Germans, the Bolsheviks were forced into concessions on a staggering scale. Most of western Russia, including Poland, the Baltic provinces and modern Belarus, had to be given up. The great salient that had made Russia a great power in Europe was simply wrenched away. But just as extraordinary was the loss of the Ukraine, where the invading Germans had promoted a separatist regime, the Rada. Russia's great grain basket (source of much of its export earnings before the war), its main source of coal, and its prime industrial centres were now controlled by a German client state. Indeed, the Brest-Litovsk treaty seemed only the prologue to a larger drama. German military power was set to extend all round the Black Sea, âliberating' Russia's colonial territories in the Caucasus and perhaps beyond the Caspian. And, as civil war brewed in Russia's remaining lands, the grip of the centre on its old imperial periphery in Central Asia and the Far East provinces looked certain to fail. One great rivet that had clamped Eurasia together was breaking in half.

In fact the implosion of Russia opened the door to a vast reordering of the whole Eurasian land mass. Its immediate effect was to allow the Germans to transfer men from the east to knock out France and Britain before American help could become decisive. In the great offensive of MarchâJune 1918, they came very close. As the armies of the Entente reeled under the blow, it seemed in London as if a catastrophic change in the shape of the war was about to unfold. France and Italy (after the disaster at Caporetto, in October 1917, when the Italian armies were thrown back by the Austrians) were on the verge of defeat. That would mean British (and American) withdrawal from the European mainland, where German control would become complete. What remained of Russia would be of no account: it is unlikely that the Bolshevik regime would have lasted long if Germany had won the war. With their Ottoman ally, and their newfound friends in the Ukraine and the Caucasus, the Germans would become the dominant power in the Near and Middle East. They would make Iran a client, and advance on the Gulf. British India would be in their sights. Nor could London be sure that, in this appalling scenario, its Japanese ally would not change sides, to protect the wartime gains it had made in North East Asia. Even if peace was made, under these conditions it was bound to be followed by a cold imperial war. So exposed in Europe, Britain would become much more dependent on its American ally. The âSouthern British World' (a contemporary phrase in British grand strategy) in Africa, India and Australasia would have to become a huge armed camp for an indefinite time, with unforeseeable consequences for its political future.

9

The only safeguard against the global impact of German domination of Europe, reasoned British leaders, was to redouble efforts to control the crossroads of Eurasia in the Middle East. From March 1918, small British forces were dispatched to rally the resistance of the former Russian dependencies in the Caucasus and Central Asia against the GermanâOttoman alliance. Another British unit, âNorperforce', was sent to âNorth Persia', to ensure a sympathetic regime in Tehran. A great newoffensive was planned against the Ottoman army in Palestine as soon as men could be spared from the western front and newtroops be raised in India. The absolute necessity to break up the Ottoman Empire and to impose a form of British paramountcy

across the vast land area between Afghanistan and Greece became a radical newelement in British foreign policy, inconceivable before 1914.

10

A British-controlled Middle East would join partitioned Africa as a dependant of Europe â though a Europe divided (as still seemed likely as late as July 1918) between a continental hegemon and an embattled offshore power. But before the realism of this amazing plan could be properly tested, the military tide began to turn in the west.

The Germans had tried to break the stalemate of trench war with an all-out offensive. But, like the British and French in 1916â17, they found it hard to maintain their momentum in a pattern of warfare that favoured defence. Despite an early breakthrough that nearly cut the Anglo-French armies in half, their advance had run out of steam by the middle of June. A well-organized counteroffensive began driving them back. The last hope of German victory before American manpower could make itself felt began to fade away. After heavy losses in early August, and the âblack day of the German army', the âsilent dictatorship' of Hindenburg and Ludendorff began to lose its nerve. Amid signs of social unrest at home, and with worsening news on the Balkan and Palestine fronts (where Allenby destroyed the Ottoman army at Megiddo), it decided to ask for an armistice. The Allied side, where the French and British had to count the cost of continuing the war in terms of an ever-increasing American influence, lacked the will to press on for an outright German surrender. When the armistice came, on 11 November, the German front line still lay across Belgium. The invasion of Germany would have taken the war into a further year. Here lay the origins of the pervasive myth of the inter-war years: that the German army had not been beaten, but had been âstabbed in the back' by socialist treachery in domestic politics. Here lay the root of the persistent belief that the peace that followed took no account of the military balance sheet and was a cruel injustice to Germany's status as one of Europe's great powers. Because of that, the huge military struggle on the western front turned out to have settled nothing. The armistice was precisely that: a temporary truce in Europe's second Thirty Years War.

The peace conference that assembled in Paris in January 1919 had as its first priority drawing up the terms of a treaty between Germany

and the four-power coalition that had forced it to abandon the war. These included the issue of Germany's boundaries, the demand for reparations for wartime damage, and (to justify reparations) an admission of German guilt for having started the conflict. But there was a huge extra agenda. The most pressing item was a new states system for Eastern, Central and South East Europe to replace the shattered imperial order of Romanovs, Habsburgs and Hohenzollerns. No less urgent was the political future of the former Ottoman Empire, and of the old tsarist borderlands in the Caucasus and Central Asia with their mixed populations of Christians and Muslims. In East Asia, where China had entered the war on the side of the Allies in 1917, the peacemakers were faced with the claims of Japan to the German sphere in Shantung (fiercely opposed in China). There was the awkward fact of Japan's growing power on the North East Asian mainland, where it had occupied Vladivostok in April 1918 â ostensibly as part of the Allied intervention to keep Russia from succumbing to German control. Both formed part of the larger question of whether Japan would be allowed to dominate post-imperial China. Taken together, this amounted to a programme for the political reconstruction of almost all of Eurasia. Compared with this, deciding which of the victor powers was to administer the Pacific and African colonies taken away from Germany, and under what terms, seemed a tiresome detail. Indeed, it was much the easiest issue to settle.

11

On the greater issues, the odds against agreement were appallingly high. Quite apart from the rivalry of the victor powers, peacemaking was complicated by colossal uncertainties. Who would win the civil war between Reds and Whites that was now raging in Russia? Would Russia's revolutionary politics spread to the rest of Europe? Would the newnation states envisaged for Europe agree on their frontiers? Could the ethnic claims of Turks, Greeks, Armenians, Arabs and Jews be reconciled with each other and with the wartime agreements to partition the Ottoman Empire between Britain, France and Italy? What would happen if they could not? And who on the ground would emerge in control of Russia's former Asian empire? Had the victor powers enjoyed overwhelming military power and used it in unison they might have hoped to impose their favoured solutions (had they been able to agree on them). The reality was different. Demobilization

was swift and war-weariness strong. Restless opinion at home made consistent policy hard. The result was a climate almost made for upheaval. On the one hand, local leaders had every incentive to recruit local armies and force through local solutions, presenting a fait accompli to faraway peacemakers and their underpowered agents. On the other, the newideology of national self-determination, eagerly propagated as a weapon of war by the British and the Americans and upheld as the leitmotif of the peace conference in Paris, dangled hope of recognition to any plausible nationalism. Amid ample signs on all sides that Eurasia's old imperial order had been washed away by the flux of war, it was hardly surprising that revolutionary symptoms now appeared almost everywhere.

By March 1919a general crisis of European control was well under way across much of Asia. On 10 March, British officials in Egypt reported riots in Cairo after the arrest of a leading nationalist, Saad Zaghlul. Within days the violence spread through the delta towns and into upper Egypt. A thousand Egyptians had died before the revolt was suppressed; the political unrest was much harder to quell. In early April there were violent disorders in British-ruled India. In the province of Punjab (the main recruiting ground for the Indian army), the British faced what they thought was an organized rising to smash their control. Their savage reaction reached a bloody climax in the events at Amritsar on 13 April, when nearly 400protesters were shot by troops. In Anatolian Turkey, parts of which had been assigned by the peacemakers in Paris to an expansionist Greece, a national uprising began in May under Mustafa Kemal, a pre-war âYoung Turk' and a wartime general in the Ottoman army. In south-eastern Anatolia, a Kurdish revolt threatened the precarious grip of the British occupation in the province of Mosul. In the Arab Middle East, where Damascus was the epicentre of political action, the great powers' permission for a free Arab state was awaited impatiently, but with growing suspicion. In the old tsarist empire, the struggle for freedom by Bashkirs, Tatars, Kazakhs, Azerbaijanis and the Muslim peoples in Russian Central

Asia that had begun with the Russian Revolution of 1917 also hung in the balance. Most momentous of all, events in May 1919 showed that the Chinese revolution, apparently stalled since 1911, had at last taken off. The May Fourth demonstrations in Peking, whose immediate target was the decision in Paris that Japan should retain a sphere of influence in Shantung, signalled a far wider movement of national consciousness. That China must be a constitutional state, not a dynastic empire, nowseemed accepted by all educated opinion. The restoration of full Chinese sovereignty, the end of foreign (especially British) enclaves and privileges, and China's acceptance as an equal member of the international community became the objectives of this newChinese nationalism. The implications for East Asia, and for the colonial states that bordered China's territories or had Chinese minorities, were bound to be large.