After Tamerlane (58 page)

Authors: John Darwin

Of course, these movements and others like them had not sprung from nowhere in 1918â19. In most cases they were built on older demands for nationhood, autonomy or at least recognition as a distinct community. Involuntary mobilization for war (as soldiers or suppliers), or the vicarious suffering of its hardships and losses, inflamed the grievances and widened the constituency of nationalist opposition. When the war ended or (as in Russia's case) imperial authority collapsed, the political climate soon reached fever heat. It was stoked by a mixture of fear and hope: fear that the repression of wartime would be continued indefinitely and the chance of freedom lost; hope that the cracking of Europe's imperial order and the promises of self-rule broadcast by the Allies in 1918 would mark the beginning of a newânational' age. Gaining recognition for their cause in Paris, persuading the peacemakers to right historic wrongs, winning a licence for their separate existence were key objectives of nationalist leaders: in Egypt, Turkey, the Arab lands, Iran and China. When this gambit failed, or where it was hopeless, they pulled the trigger for more direct means.

The results were mixed. In Egypt, the brief explosion of popular violence left a bitter residue of political unrest. A British inquiry attributed much of its fury to wartime resentment: of inflation, shortages and the conscription of labour and animals for the imperial war effort against the Ottoman Empire. But the Egyptian elite were deeply

suspicious that the British intended to absorb Egypt more fully into their imperial system at the end of the war (Egypt had never been formally annexed). The Wafd (or âdelegation') party was formed to take Egypt's case to the Paris peace conference and win international support for the virtual independence (or better) that the country had enjoyed before 1882. The brusque British refusal to permit this appeal, and the jailing of the Wafd leaders to pre-empt a popular campaign, produced the breakdown of order of March 1919 as strikes and demonstrations and the effects of rumour and fear fused with wider sources of social tension in a deeply stratified society. When the violence died down it was replaced politically by a climate of bitter resentment. The British controlled Egypt through Egyptian ministers and the Egyptian monarch (renamed the sultan in 1917). They preferred this indirect rule as a less confrontational way of securing what they wanted: a monopoly of foreign influence and absolute security for the Suez Canal, the lifeline of their empire in the East. Egypt, they argued, could never enjoy a âreal' independence. But after March 1919 no Egyptian minister would stay in office unless the British promised exactly that. Without Egyptian ministers, the British faced all-out opposition from every shade of local opinion: non-cooperation by officials; denunciation by teachers and clerics; strikes by key workers in transport and utilities; perhaps even recourse to the âIrish' methods they feared the most â boycott, assassination and terror. Between March 1919 and February 1922 they struggled to find a formula that would appease a âmoderate' group of Egyptian leaders and split the nationalist coalition against them. It was only when they declared Egypt to be an independent state (but bound to followBritish âadvice' in defence and foreign policy) that the fierce anti-British feeling began to die down.

12

In the Arab lands the issue was more complex. The force behind demands for an Arab state was the alliance between Feisal and his Hashemite clan (the hereditary rulers of the holy places in Ottoman times) and the Syrian notables. It was Feisal, as the son of the sharif of Mecca, who had led the Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire after 1916, with British help and encouragement, and who had extracted the notorious promise of an Arab state at the end of the war. The Syrian notables had taken the lead before 1914 in urging an Arab consciousness against Ottoman overrule â indeed Syria (Suriyya)

had begun to be thought of as an Arab homeland from the 1860s.

13

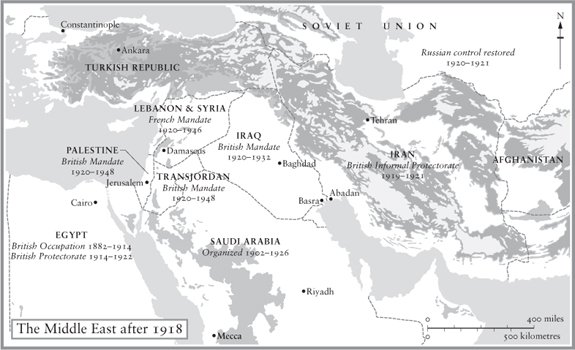

Both Feisal and the Syrians had reason to be fearful. They knewthat the Palestine district would be separately governed, partly to allow the creation of a ânational home' for Jews. They also knew that in 1916 the British and French had agreed a partition of the Arab lands, placing modern Syria and Lebanon under French supervision and most of modern Iraq under British. To make matters worse, it soon became clear that the newBritish regime set up in Baghdad regarded the idea of an Arab nation as at best irrelevant, and at worst absurd. It had no intention of allowing the Baghdadi notables to make common cause with their friends in Damascus. What Feisal hoped for was a British change of heart: a decision to repudiate the agreement with France and create an Arab state or states under a loose form of protection. The British had allowed him to head a provisional government in Damascus under their overall control. Feisal himself sought to buy off the French and to assure Jewish leaders that their ânational home' would be safe under an Arab government. But his hopes and diplomacy were both in vain. By the end of 1919 the British had agreed to pull their troops out of Syria and make way for the French. In the following spring the European victor powers (the United States had withdrawn into âisolation') decreed (as the Supreme Council of the League of Nations) that the Arab lands would be divided up and governed as âmandates', until each unit was deemed fit for self-rule. Palestine and Transjordan would be British. So would the new state of Iraq, an awkward combination of three disparate provinces: Mosul, with its large Kurdish population; Baghdad, which was dominated by a Sunni Muslim elite; and Basra in the south, which was overwhelmingly Shia. But Syria would be French and cut down to size, losing Lebanon (to be a separate French mandate) as well as the British mandates to the south. In a last act of defiance, a âSyrian Congress' assembled at Damascus to denounce the mandates and call for Arab unity and independence under Feisal as king. With a makeshift army, Feisal tried to resist the French occupation. After a hopeless battle in July 1920 he fled into exile.

If the dream of âGreater Syria' as a free Arab nation had been wiped from the slate, the Anglo-French partition was still far from secure. Defiance in Syria had spread to Iraq. The Baghdad notables, some of

them linked through a secret society with Feisal's supporters, fiercely opposed the colonial-style rule the British had imposed at the end of the war. In June 1920 their political grievances found a massive echo. In the rural communities of the Euphrates valley, pent-up resentment at foreign rule and taxation set off an explosion of violence. As the British struggled to contain it, deploying more and more troops and spending more and more money, the case for installing a suitable Arab-led government became more and more urgent. It was Winston Churchill's idea (Churchill was colonial secretary with responsibility for the Arab Middle East, but not Egypt) that the now-exiled Feisal would be the best choice as leader, since only he, so it seemed, would have the skill and prestige to keep this ramshackle creation together in one piece. Yet whether even he could do so, and then on what terms, were still profoundly uncertain. For the fate of Iraq was only part of a larger question. By the end of 1920 it seemed more and more likely that a newTurkish state, hostile and aggressive, would rise from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire and claim its old place in the politics of the region. In 1921â2, Mustafa Kemal imposed the authority of his Turkish republic across most of Asia Minor, smashing both British hopes of a weak Turkish client state ruled by the sultan and the grand Greek project to turn much of western Anatolia into the âIonian' extension of a âGreater Greece'.

14

In September 1922 he captured Smyrna (Izmir) and was marching on Constantinople, the old imperial capital, when he met a small British garrison stationed at Chanak to guard the Dardanelles. A vast crisis nowloomed. If a newwar began between the British and the Turks, the political future of the whole Middle East would be back in the melting pot.

15

The actual outcome after months of tense diplomacy was a treaty of peace agreed at Lausanne in July 1923. It recognized Turkey as an independent republic. It restored Constantinople as a fully Turkish city. (It was officially renamed âIstanbul' in 1930.) It voided the claims for European spheres in Turkey's Anatolian heartland. It scrapped the old system of foreign extraterritorial privilege (the âCapitulations') and released Turkey from the thrall of the pre-war Debt Administration. It provided for an exchange of populations, clearing Turkey of âGreek' Christians and Greece of Muslim âTurks': a portent of things to come.

16

The Turks accepted the demilitarization

Straits, accepted the loss of their Arab empire, and agreed to arbitrate their special claim to Mosul. It was a remarkable compromise. It reflected the reluctance of both British and Turks to resume the armed struggle, the modest reassertion of Russian influence in the region after 1920 (see below), and the eagerness of Kemal to build his new Turkish state along the European lines favoured by pre-war reformers. It was the crucial stage in solidifying the grip of the British and French on their newArab mandates. It allowed France a free hand to parcel up Syria and crush the great revolt that followed in 1925â7. It made a cheap British presence possible in Iraq, where the British traded air power (to help crush Feisal's opponents) for the bases they needed to guard the approach to the Gulf and reach India by air. Nevertheless, the scale of post-war resistance had left a deep mark on the Middle East's politics. In Syria and Palestine, Arab claims to self-rule had been roundly rejected. But in Egypt and Iraq the British had been forced to agree to wide local autonomy and acknowledge the claim of both states to independence â in 1922 to Egypt, a decade later to Feisal's Iraq â as a quid pro quo for Britain's control of their strategic zones, the Suez Canal especially. Even Transjordan had been given its own (Hashemite) king. Despite the trauma of partition, the Arab Middle East had not been transformed into a fully colonial region. The sense of pan-Arabness, awake before the war, had not been extinguished. There were many spaces left in which it could grow. European authority (it was mainly British) was shallowly rooted in social and cultural terms. It depended heavily on geopolitical contingency: the temporary easing of great-power rivalry with the eclipse of Germany and the isolation of Russia. In an age of depression, it gained little help from the spread of trade or the region's accession to the international economy. The growth of the oil industry was too long delayed (the Middle East produced only 1 per cent of world output in 1920, only 5 per cent in 1939, almost all of it from south-west Iran) to allowit to serve as a real Trojan Horse of European imperial influence. Once the brief excitement of war imperialism had passed, there was little enthusiasm for an Arab empire in either Britain or France â especially one that was going to cost money.

17

If the Middle East's partition was the high tide of empire, it was the tide that turned soonest, the imperial moment that was shortest.

It was Turkey and Iran that seemed to gain most from the era of turmoil between 1918 and 1923. Both had been faced with humiliating relegation to protectorate status or worse: Turkey as the occupied rump of the Ottoman Empire; Iran as the client state of a victorious Britain. Both were to benefit from the dramatic easing of the external pressures that had been almost unbearable before 1914. Neither Russia nor Britain was eager to intervene actively in their internal affairs after 1923; each was preoccupied with domestic demands. The chance was seized by two remarkable state-builders to drive through the changes of which reformers had dreamed before 1914. Mustafa Kemal (later named âAtatü rk') assembled a Turkish republic in the Anatolian core of the ruined Ottoman Empire, largely âcleansed' of its Christian minorities. In Kemal's republic, conservative Islam was the principal foe, the main obstruction to a modern state able to hold its own against ill-intentioned great powers. New laws about clothing (banning the brimless fez that allowed the Muslim faithful to touch their head to the ground), the alphabet (replacing the Arabic script with Latin-style letters), education (outlawing religious instruction in madrasas) and surnames (Turks were obliged to acquire Western-style family names) dramatized the conflict between a Muslim identity and the loyalty demanded by the secular state from its ânational' citizens.

Behind Kemal's success lay the ânational' movement created to win the war with the Greeks and restore Turkish independence. Kemal commanded an army that was (and remained) deeply committed to his national programme. He also inherited a recognizably modern administrative structure from the Ottoman reforms before 1914. In Iran the going was bound to be tougher. There the war and its aftermath had sharpened the conflicts within Iranian society, all but destroying the central government in Tehran. Foreign occupation (by British, Russian and then Soviet forces), breakaway governments, ethnic movements, social unrest and tribal self-assertion threatened to make the country ungovernable. In these desperate conditions, the military coup in February 1921 by Reza Khan, an officer in the Cossack Brigade (the only regular force under Tehran's nominal control), was widely supported, and Reza was able to negotiate a Soviet and British withdrawal. Once established in power, he quickly

adopted a programme of change strikingly similar to Kemalist Turkey's. A large army was built up to crush provincial rebellions and tribal indiscipline. Newrailways and roads increased the government's reach. Laws about headwear (requiring caps or hats), on the adoption of surnames (Reza took the name âPahlevi'), on the treatment of women and outlawing the veil signalled Reza's main target: the influence of the mullahs. Faced with resistance, Reza became a virtual dictator: in April 1926 he crowned himself shah. Huge dynastic estates and extensive court patronage were added to the power supplied by the army and bureaucracy. Reza had fashioned a newimperial state far stronger than anything that the Qajars had hoped for. He was able to do so without the reliance upon foreign funds or concessions that had rallied the enemies of Qajar reform. The key reason for this was a newsource of wealth. For, although Reza stopped short (as prudence dictated) of taking control of the oilfields just north of the Gulf from the British-owned company that held the concession (the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, of which the British government held 51 per cent of the shares), his revenues profited from the hundredfold increase in the income they earned after 1913. But for him, as for the republic that Atatü rk (who died in 1938) had made, the real test would be felt when the geopolitical lull they had exploited so skilfully collapsed into war after 1939.

18