After the People Lights Have Gone Off (4 page)

Read After the People Lights Have Gone Off Online

Authors: Stephen Graham Jones

Tags: #Fiction, #Ghost, #Short Stories (Single Author), #Horror

I stood there beside it and I held my breath as long as I could, the skin of my face drawing tight in the heat, my heart shaped exactly like two hands holding each other, and when I finally turned to go home, Lucas was there, and Thomas, and Trino, and they hid me, and they never told, and I’ll never leave this town, I know.

Not for the usual reasons, though.

In the flames that night before anybody got there, I saw a boy, the front of his pants wet with blood, and I saw Marcus, wearing his swim goggles, and I saw a pale white shepherd’s crook ahead of them, leading them through, leading them on.

Someday she’ll come for me too, I know.

I’ll be waiting.

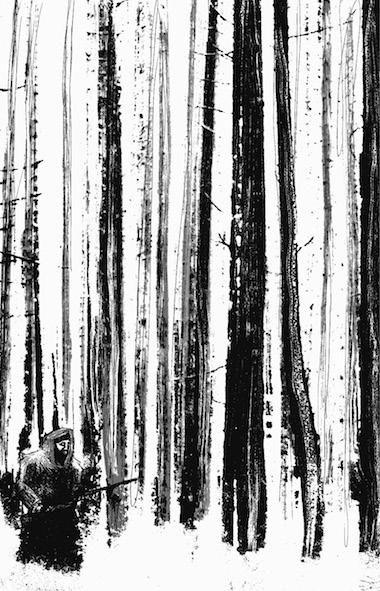

ing, waiting for the sun to glint off some elk horn, Junior tracked himself back, stepping in his own boot prints when he could. And it’s not that he didn’t understand: coming out an hour before dawn, walking blind into the blue-black cold, some of the drifts swallowing you up to the hip, it wasn’t the same as watching football on the couch.

The bear tracks they’d seen yesterday hadn’t helped either, he supposed.

Since then, Junior was pretty sure Denny wasn’t so much watching the trees for elk anymore, but for teeth.

He was right to be scared, too. Junior was pretty sure he had been, at that age. But at some point you have to just decide that if a bear’s going to eat you, a bear’s going to eat you, and then you go about your day.

One thing Junior knew for sure was that if he’d been in walkie contact with

his

dad, then there wouldn’t have been any meets at the truck.

Junior was doing better, though. It was one of his promises.

So he eased up to the truck, waiting for Denny to spot him in the mirror. When Denny didn’t, Junior knocked on the side window, and Denny led him fifteen minutes up a forgotten logging road, to a thick patch of trees he’d probably stepped into for the windbreak, to pee.

“Whoah,” Junior said.

It was a massacre. The bear’s dining room. At least two winters of horse bones, some of them bleached white, some of them still stringy with black meat.

Junior had to admit it: this probably would have spooked him, twenty years ago.

Hell, it kind of did now.

“They’re supposed to be asleep,” Denny said. “Right?”

Junior nodded. It was his own words. The tracks they’d seen yesterday, he’d assured Denny, would lead them to a musty den if they followed them.

“Let’s go work the Line,” Junior said, and Denny was game.

The Line wasn’t the one that separated the reservation from Canada, but from Glacier Park. It was just across the road from Chief Mountain.

Twenty-five years ago, Junior had popped his first buck there, across a clearing of stumps he’d been pretending just needed tabletops to make a proper restaurant. That had been his secret Indian trick to hunting, back then: to not hunt. The same way you never find your wallet when you’re actually looking for it.

Just, keep a rifle with you.

Junior dropped Denny off right at the gate, told him to walk straight up the fence, and keep an eye out.

“Check?” Denny said into his walkie, stepping out, gearing up.

“Check,” Junior said into his walkie, his own voice echoing him.

“Just walk back to Chief mountain if you lose the fence,” Junior told Denny. “You’ll hit the road first. I’ll be up at that other pull-out. Maybe you’ll scare something my way, yeah?”

“Yeah,” Denny said, looking at the tree line with pupils shaped like bears, Junior knew.

Junior left him there, pulled over a quarter mile or so up the road.

He hadn’t been lying about them scaring elk or some whitetail into each other’s paths, either. It was how he’d learned to hunt, his uncles pointing down this or that coulee, telling him to slip down there, make some noise, they’d shoot anything that spooked up.

Denny wasn’t just a brushdog, though.

Really, Junior was half-hoping to scare something over to

him

. Every animal on the reservation, it knows to run for the Park when Bambi shooters are in the forest.

The kid deserved an elk this year, or a nice buck. Something to hook him into

this

way of doing things, instead of all the other ways there always were, in Browning.

Junior pulled his gloves on, locked the door, and beat his way through the brush, keeping his rifle high like he was a soldier fording a river, not a latter-day Indian with a burned arm and forty-percent disability.

Maybe a half hour into it, half-convinced the world was

made

of trees all blown over into each other, the ground under his boots tilted up sharply. Junior followed, eager for an open space.

Like was supposed to happen, the trees thinned the windier it got—the

higher

Junior got—until he stepped out of the crunchy snow, then onto the blown-flat yellow grass of . . . not quite a meadow, but a bare knob, anyway. One of a hundred, surely, if you were flying above. But, standing on it, it was the only—no, it

wasn’t

the only one: directly to the west of Junior, like a mirror image, like he’d walked up to his own reflection, was another bare knob.

Except this one, it had a little pyramid of black rocks right at the very crest.

Junior looked away to search his head for the word, finally dredged it up:

cairn

.

Like what you arrange over your favorite dog, when the ground’s frozen and you can’t cut into it with a shovel. Like what you put over your favorite dog for temporary, promising the whole while to come back in Spring, do it right.

But you never do, Junior knew.

Because you don’t want to have to see.

Except—who would bury a dog way the hell out here?

Maybe this was some super-old grave, some baby from the Lewis and Clark clown parade.

Or maybe it was older. Maybe it was real.

Junior brought his rifle up, leveled the scope on the

cairn

and steadied the cross-hairs against the wind, gusting like it knew Junior was trying to draw a bead.

The rocks looked just the same, only closer up now, and trembling, the scope dialed up to 9.

Trembling until they smudged out, anyway.

Junior took an involuntary step back, pressing the scope harder into his right eye socket—

stupid, stupid

, he said to himself—and then got things focused again.

When there was just blackness again, a

fabric

texture to it, Junior lowered the scope, looked across with his real eyes.

Denny.

He’d lost the Line, it looked like, was falling up through the trees as well, his rifle slung over his shoulder.

Instead of doing it like Junior had taught—two steps, stop, listen, look, wait, then two more steps—Denny was just stumbling across the yellow grass, his face slack like he’d been out there for hours, not thirty minutes. One of his gloves was gone, Junior noted.

His first impulse was to put the scope on Denny, so he could give a report later.

Saw you out there, Cold Hand Luke. Didn’t you see me?

Except, even if he drew the bolt back on his rifle, just the idea of putting his son in those crosshairs made him feel hollow under the jaw.

Saw you out there, son. By those black rocks.

Junior said it aloud, the wind pulling his words away.

And Denny

was

lost, Junior could tell. With Chief Mountain looming behind, the Park right there to the west, and Canada just a rifle shot to the north, if that, the kid had managed to get off-track somehow. Again. And in spite of how the Line was a three-strand

fence

for the first couple hundred yards. All you had to do then was walk where the fence would have been, if it went on. It didn’t even take a sense of direction. The Park Service had come through with chainsaws back when, shaved a line through the woods, to tell the Indians what was America, what wasn’t. Just follow the stumps, kid.

Junior

had

told him that at some point, hadn’t he?

Now Denny was doing one thing Junior had taught, anyway: going up the closest hill to eyeball for a landmark. To find Chief Mountain, like Blackfeet had been doing since forever.

“Looking the wrong way there, son,” Junior said, using his best John Wayne voice.

Soon enough, Denny was going to have to look over, see Junior waiting there for him. Even if he wasn’t scoping for Chief Mountain or for the elk he was supposed to be after, then he would at least be checking for the bear he probably thought he was climbing away from. That he could probably hear huffing and grunting right behind him.

His knob of hill was steep enough now that he was having to reach ahead, touch the ground with his bare fingertips.

Junior took a step higher, his back straightening, some alarm ringing behind his eyes.

It was nothing. Stupid.

You’re

the one being stupid, Junior told himself, in his own dad’s voice.

With his hands to the ground like that, Denny had looked like something else. Junior wasn’t even sure what. A four-legged, as the old-time Blackfeet said it, in books written by white men.

And Denny

still

wasn’t looking across.

“Hey!” Junior called, but didn’t put any real force behind it.

Still, Denny’s head rotated over at an angle Junior associated with owls more than people, his face snapping up perfectly level, his jaw hanging loose, mouth a skewed black oval, eyes vacant even at this distance, and Junior’s breath caught hard enough in his throat that he had to cough.

By the time he was able to look back up, Denny’s front hand was reaching forward delicately to the cairn, like warming his palm by a cast-iron stove. Junior brought the soft back of his glove to his face, to rub the blear and the heat from his eyes.

And Denny.

The bald knob across from him, it was just that again.

No rocks, no son. Nothing.

Junior lifted the walkie, said, “Den-man? You out there?”

Fifteen seconds later, the walkie crackled back in Junior’s hand.

No words, just static. Open air.

Because of distance, he told himself.

Because these walkies had been clearance over in Cutbank, were pretty much line-of-sight pieces-of-crap.

When Junior stepped out of the tree line and into the ditch thirty minutes later, ready to tap the horn three times—their signal—there in the passenger seat of the truck was a shape that slowly assembled itself into Denny: hat, jacket, safety-orange gloves, frosted breath.

Behind the steamed up window, he turned his head to Junior and watched.

•

Because Deezie was in Seattle sitting by her dad’s hospital bed, Junior cracked open two cans of chili and poured them into a pan, shook their can shape away.

Denny was in his room, peeling out of his hunting gear. If Deezie were here, he’d have had to strip at the door.

Junior set the pan down into its ring of flame.

On the ride home he’d said the obvious aloud to Denny: that he’d found his other glove, yeah? Good thing they were orange, right?

Denny had looked at his hands in his lap, then out the window.