Afterlands (27 page)

Aye aye, sir! Anthing hollers.

On the way back, Meyer insists on standing in the bow, waving solemnly like a returning monarch as they approach the castaways lining the shore of their home.

That evening the sea sweeps over the floe and washes them out of the tent. Tyson orders everything and everyone into the whale-boat, where they slump together in a democracy of terror and cold. Through a haze the setting sun appears grey and hollow and cold, and the wind seems to be howling straight out of it, as if from the mouth of a pale tunnel. She sits on the middle bench with Punnie on her lap, in a ready boat on a hard surface, waiting for the flood to lift them. The Flood, this is the story she tells the child now, sometimes quoting verses word for word. How those good people with their mated animals—yes, lions and camelopards as well—drifted for a long time over the flood-waters, but then they sent forth land-birds, and at length the dove returned not again unto Noah, and he and his family came safely unto shore. Punnie, whispering, relays the story to her glumly staring doll, interpreting into Inuktitut; for Elisapee, she affirms, speaks no English.

Soon the Gosling Moon will begin, little one. The land-birds will lead us home, too.

They were lucky to have so many pairs of animals to eat, the child says.

They try to sleep as the night engulfs them, and Tukulito hears Mr Kruger clacking his jaws, shuddering over his frozen feet. In her heart she feels the wrong of the lieutenant’s believing him to have been the thief. Two days ago, or perhaps three—nothing is quite clear anymore—she confided to him, the lieutenant, that Mr Kruger was innocent of this charge, for she herself was the thief; and then she quickly related her full story. At first he was silent, but his beard had a bitterly smiling look. Then he said, I can’t credit that you would break so with native custom, Hannah. You mean to protect him, I see. When she replied, And why should I wish to do that, sir? he only smiled in the same chilling, cheerless manner, the pupils of his eyes sinking into the deep-fathomed blue around them. So he too appears to hold this false belief about herself and Mr Kruger. Of course she said nothing on the matter; but she cannot help wondering if Mr Kruger has made some lying claim.

From time to time high seas swamp the floe—not enough to lift the boat, though they rock it a good deal—so that all are confined aboard. All are throttled with thirst; the freshwater ice is now polluted with brine and there is no blubber to melt it anyway. The men are again famished. It has been days since Ebierbing has taken a seal. Tukulito can read their hunger in the way several of them consider her and Punnie, and especially in how they look skittishly away: Jamka, with his green-scabbed cheek, who now takes pains to avoid her, trying to keep a crewman between himself and her at all times, which is easily done, for Kruger always quietly inserts himself, though whether to protect her, or to be closer to her, or both, she is unable to interpret.

At dawn she wakes in the boat with Punnie right inside her amautik. Somehow the child has burrowed up inside it in the night so that Tukulito looks, and feels, massively pregnant. Feels even the warmth of pregnancy. She takes the revolver from her outer pocket and pushes it into her boot. It is consoling to know that with this, her third child, death will not be able to separate them, and they will sink as one flesh: what they never really were. How wrong some people are to suppose that one does not love a

paninguaq

, adopted girl, “pretend daughter,” the same way. As if the warmth of flesh and blood could ever surpass the fire of the soul’s love. Behind her at the tiller, Tyson, demoted to boyhood in his joy, cries in a breaking voice, Oh, Hannah, look! A raven is gliding toward them not far above the ice, inspecting them. In the wake of the straggling dovekies that have passed lately, this bird looks enormous, a thing considerably too large to be airborne. Updrafts dance in the finger-like feathers off the backs of her wings. So, here is the land-bird that her story has promised Punnie. Punnie!—wake up, little one, come out and see!

Her voice is in the same condition as Tyson’s, but the child will not emerge.

Fevered with hunger and familiar since childhood with the spirit of such creatures, Tukulito is now peering down from high above, through the raven’s shrewd, currant-black eyes, on a floe where everything is still alive and, for now, there is nothing to scavenge. With a coarse, scraping call—having astutely noted the company’s position—the bird circles back toward land.

Easter Sunday. Conditions increasingly desperate. We seem forgotten here. Men obeying still but some wear dangerous Looks. This Hunger is disturbing every Brain. Last night the Stars looked heartless to me & the Aurora a gawdy & vacant show! Can right no more now. Must sleep

.

April 14, Morning

. I think this must be Easter-Sunday in civilized lands. Surely we have had more than a forty days’ fast. May we have a glorious resurrection to peace and safety ere long!

Last night, as I sat solitary on my watch, thinking over our desperate situation, the northern lights appeared in great splendor. I watched while they lasted, and there seemed to be something like the promise accompanying the first rainbow in their brilliant flashes. The Auroras seem to me always like a sudden flashing out of the Divinity: a sort of reminder that God has not left off the active operations of his will. So we must continue to trust. This, with my impression that it must be Easter-Sunday, has thrown a ray of hope over our otherwise desolate outlook.

April 18

. Blowing strong from the north-east. There is a very heavy swell under the ice.

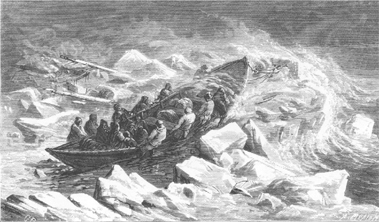

At 9 P.M., while resting in our tent, we were alarmed by hearing an outcry from Lundquist on the watch; and almost at the same moment a heavy sea swept across our piece, carrying away every thing on it that was loose. This was but a foretaste of what was to follow; we began shipping sea after sea, one after another, with only a few minutes’ interval between each. Finally came a tremendous wave, carrying away our tent, skins, and most all of our bed-clothing. Only a few things were saved, which we had kept in the boat; the women and children were already there, as they were every night, or the little ones would certainly have been swept to watery graves. All we could do now was to try and save the boat. So all hands were called to man it in a new fashion—namely, to hold on to it with might and main, to prevent its being washed away. Fortunately, we had preserved our boat warp, and had also another strong line, made of strips of oogjook-skin, and with these we secured the boat to projecting vertical points of ice; but having no grapnels or ice-anchors, these fastenings were frequently unloosed and broken, and the boat could not be trusted to their hold. All our additional strength was needed, and we had to brace ourselves with all the strength we had.

As soon as possible I got the boat, with the help of the men, over to that edge of the floe where the seas first struck; for I knew if she remained toward the farther edge, the gathered momentum of the waves as they rushed over the ice would more than master us, and the boat would go. It was well this precaution was taken, for, as it was, we were very nearly carried off, boat and all, many times during this dreadful night. The heaviest seas came at intervals of fifteen or twenty minutes, and between these came others that would have been thought very powerful if worse had not followed.

There we stood all night long, from 9 P.M. to 7 A.M., enduring what I should say few, if any, have ever gone through and lived. Every little while one of these tremendous seas would come and lift the boat up bodily, and us with it, and carry it, and us, across the ice almost to the opposite edge of our piece; and several times the boat got partly over the edge, and was only hauled back by the strength of mortal desperation. Then we must push and pull and drag the boat right back across the floe to its former position, and stand ready, bracing for the next sea. Had the water been warm and clear of

débris

, it would have been hard enough. But it was freezing and full of loose ice, rolling about in blocks of all shapes and sizes, and with every sea would come an avalanche of these, striking us on our legs and bodies, and bowling us off our feet like so many pins in a bowling-alley. Some of these blocks were only a foot or two square; others were as large as an ordinary bureau, or larger.

And so we stood, hour after hour, the sea as strong as ever, but we weakening from the fatigue, so that before morning we had to make Hannah and Hans’s wife leave their children and get out to help us. I do not think Mr Meyer had any strength from the first to assist in holding the boat, only that by clinging to it he kept himself from being washed away; but this was a time in which all did their best, for on the preservation of the boat we knew that our lives depended. If we had but “four anchors,” as St Paul describes in the account of his shipwreck, we could have “awaited the day” with better hope; but “when neither sun nor stars appeared, and no small tempest lay on us, all hope that we should be saved was then taken away”—nearly all. That was the greatest fight for life we had yet had. For twelve hours there was scarcely a sound uttered, save for the crying of the children and my orders to “hold on,” “bear down,” “put on all your weight,” and the responsive “ay, ay, sir!”—which now, thank God, comes readily enough. I am afraid that a sealing ship is our only hope now; and though the season is right, we have still a ways to drift to the sealing grounds.

A FEARFUL STRUGGLE FOR LIFE

.

Kruger grips the gunwale amidships, bracing his numb feet on the ice in stance for the next assault. Through the moonless dark the sea is distinguished from the sky only by its pale-glowing, incessant cargo of ice pans and chunks and pash and frazil which, like phosphorescence, chart out the violent flexing of the waves. When the larger swells approach, the floe dips lower and lower and Tyson at the bow yells, Hold on, men, here it comes! while beside him the soft-spoken Ebierbing hollers over the uproar, Big wave, boys, big! The hardest thing is to keep both hands on the gunwale while the sea thrashes over with its rattling barrage of ice—not raising a hand in self-protection. To do so would mean getting swept away. So the men tortoise their heads down and scrunch their bodies into the gunwale, as if under fire. Such cold and fear, Kruger’s testicles press upward hard as if trying to cringe back up inside him. His throat burns raw with salt. Every time a wave lifts the boat, flushing it clear back across the floe, he wonders if his boots will light again on ice or in the sea on the aft side.

But he has Tukulito to see him through. She is seated in the boat, on the middle bench beside him, Punnie a large bulge inside her parka. She has to grip the gunwale too, her mittened hands next to Kruger’s. Her face calms him like a full moon seen through a window on awakening from a nightmare: expressionless and benign. Sometimes her eyes are closed and she is silent and then they are open and staring ahead as she sings steadily to the hidden child—to Kruger—English hymns, and then, later, in the keening depths of the night, lullabies in her own language. By then he is hallucinating freely. Assigning German words to the lullabies, hearing a clear translation in his mind, much as lovers will instantly adapt each other’s words, even when they speak the same tongue. One time in the short spell between big waves he dozes off and wakes to her mittened hands clasped over his, holding them tight to the frozen gunwale. Then a shove from behind:

Wach auf, Roland!

It’s Anthing.

Ja

, says Kruger,

danke

. And Tyson’s voice again: Bear down, bear down … ! Minutes later Kruger in turn has to kick Herron awake. Tukulito’s head, in its pointy hood, is now resting on her mittens, on the gunwale. Kruger feels such an ache of tenderness that he can’t be sure if the salt taste on his cold lips is only brine or tears as well. How ever did the others get through this night without a woman beside them? At one point her tired eyes mesh with his and in that breath of time it seems to him that she weighs him critically, comes to some difficult decision, then thanks him for his efforts with her gaze, a slow tender blink of acknowledgment, as if to say, You are a man, or, I trust in you. His eyes are choked with tears, for some time. Some time later the highest swell yet and on its surface a thin sheet of ice like a pane of glass comes slicing downward. Kruger ducks and when he opens his eyes the boat is surging backward as if airborne, and ahead of him John Herron, cleanly decapitated, still clings to the side; then Herron’s drenched head, still attached, sticks back up from inside his parka.