Alcott, Louisa May - SSC 11

Read Alcott, Louisa May - SSC 11 Online

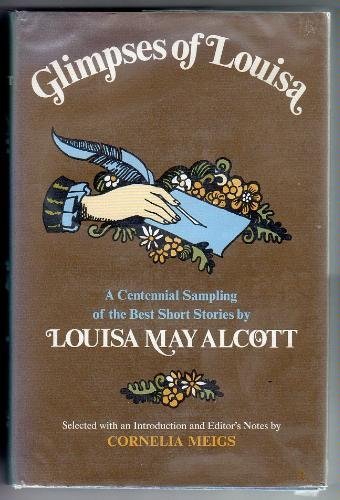

Authors: Glimpses of Louisa (v2.1)

Glimpses of Louisa

A Centennial Sampling of the Best Short Stories

Louisa May Alcott

O

NAWANDAH

"What in the world have

I

chosen?" exclaimed Geoff, as he drew out a manuscript in his turn and read

the queer name.

"A story that will just suit you, I think. The hero is an Indian, and a

brave one, as you will see. I learned the little tale from an old woman who

lived in the valley of the

Connecticut

,

which the Indians called the Long River of Pines."

With this very short preface, Aunt Elinor began to read, in her best manner,

the story of

ONAWANDAH.

Long ago,—when hostile Indians haunted the great forests, and every settlement

had its fort for the protection of the inhabitants,—in one of the towns on the

Connecticut River, lived Parson Bain and his little son and daughter. The wife

and mother

was

dead; but an old servant took care of

them, and did her best to make Reuben and Eunice good children. Her direst

threat, when they were naughty, was, "The Indians will come and fetch you,

if you don't behave." So they grew up in great fear of the red men. Even

the friendly Indians, who sometimes came for food or powder, were regarded with

suspicion by the people. No man went to work without his gun near by. On

Sundays, when they trudged to the rude meeting-house, all carried the trusty

rifle on the shoulder; and while the pastor preached, a sentinel mounted guard

at the door, to give warning if canoes came down the river or a dark face

peered from the wood.

One autumn night, when the first heavy rains were falling and a cold wind

whistled through the valley, a knock came at the minister's door, and, opening

it, he found an Indian boy, ragged, hungry, and foot-sore, who begged for food

and shelter. In his broken way, he told how he had fallen ill, and been left to

die by enemies who had taken him from his own people, months before; how he had

wandered for days till almost sinking; and that he had come now to ask for

help, led by the hospitable light in the parsonage window.

"Send him away, master, or harm will come of it. He is a spy, and we shall

all be scalped by the murdering Injuns who are waiting in the wood," said

old Becky, harshly; while little Eunice hid in the old servant's ample skirts,

and twelve-year-old Reuben laid his hand on his cross-bow, ready to defend his

sister if need be.

But the good man drew the poor lad in, saying, with his friendly smile:

"Shall not a Christian be as hospitable as a godless savage? Come in,

child, and be fed: you sorely need rest and shelter."

Leaving his face to express the gratitude he had no words to tell, the boy sat

by the comfortable fire and ate like a famished wolf, while Becky muttered her

forebodings and the children eyed the dark youth at a safe distance. Something

in his pinched face, wounded foot, and eyes full of dumb pain and patience,

touched the little girl's tender heart, and, yielding to a pitiful impulse, she

brought her own basin of new milk and, setting it beside the stranger, ran to

hide behind her father, suddenly remembering that this was one of the dreaded

Indians.

"That was well done, little daughter. Thou shalt love thine enemies, and

share thy bread with the needy. See, he is smiling; that pleased him, and he

wishes us to be his friends."

But Eunice ventured no more that night, and quaked in her little bed at the

thought of the strange boy sleeping on a blanket before the fire below. Reuben

hid his fears better, and resolved to watch while others slept; but was off as

soon as his curly head touched the pillow, and dreamed of tomahawks and

war-whoops till morning.

Next day, neighbors came to see the waif, and one and all advised sending him

away as soon as possible, since he was doubtless a spy, as Becky said, and

would bring trouble of some sort.

"When he is well, he may go whithersoever he will; but while he is too

lame to walk, weak with hunger, and worn out with weariness, I will harbor him.

He cannot feign suffering and starvation like this. I shall do my duty, and

leave the consequences to the Lord," answered the parson, with such pious

firmness that the neighbors said no more.

But they kept a close watch upon Onawandah, when he went among them, silent and

submissive, but with the proud air of a captive prince, and sometimes a fierce flash

in his black eyes when the other lads taunted him with his red skin. He was

very lame for weeks, and could only sit in the sun, weaving pretty baskets for

Eunice, and shaping bows and arrows for Reuben. The children were soon his

friends, for with them he was always gentle, trying in his soft language and

expressive gestures to show his good-will and gratitude; for they defended him

against their ruder playmates, and, following their father's example, trusted

and cherished the homeless youth.

When he was able to walk, he taught the boy to shoot and trap the wild

creatures of the wood, to find fish where others failed, and to guide himself

in the wilderness by star and sun, wind and water. To Eunice he brought little

offerings of bark and feathers; taught her to make moccasins of skin, belts of

shells, or pouches gay with porcupine quills and colored grass. He would not

work for old Becky,—who plainly showed her distrust,—saying: "A brave does

not grind corn and bring wood; that is squaw's work. Onawandah will hunt and

fish and fight for you, but no more." And even the request of the parson

could not win obedience in this, though the boy would have died for the good

man.

"We can not tame an eagle as we can a barnyard fowl. Let him remember only

kindness of us, and so we turn a foe into a friend," said Parson Bain,

stroking the sleek, dark

head, that

always bowed

before him, with a docile reverence shown to no other living creature.

Winter came, and the settlers fared hardly through the long months, when the

drifts rose to the eaves of their low cabins, and the stores, carefully

harvested, failed to supply even their simple wants. But the minister's family

never lacked wild meat, for Onawandah proved himself a better hunter than any

man in the town; and the boy of sixteen led the way on his snow-shoes when they

went to track a bear to its den, chase the deer for miles, or shoot the wolves

that howled about their homes in the winter nights.

But he never joined in their games, and sat apart when the young folk made

merry, as if he scorned such childish pastimes and longed to be a man in all

things. Why he stayed when he was well again, no one could tell, unless he

waited for spring to make his way to his own people. But Reuben and Eunice

rejoiced to keep him; for while he taught them many things, he was their pupil

also, learning English rapidly, and proving himself a very affectionate and

devoted friend and servant, in his own quiet way.

"Be of good cheer, little daughter; I shall be gone but three days, and

our brave Onawandah will guard you well," said the parson, one April

morning, as he mounted his horse to visit a distant settlement, where the

bitter winter had brought sickness and death to more than one household.

The boy showed his white teeth in a bright smile as he stood beside the

children, while Becky croaked, with a shake of the head:—

"I hope you mayn't find you've warmed a viper in your bosom, master."

Two days later, it seemed as if Becky was a true prophet, and that the

confiding minister

had

been terribly

deceived; for Onawandah went away to hunt, and that night the awful war-whoop

woke the sleeping villagers, to find their houses burning, while the hidden

Indians shot at them by the light of the fires kindled by dusky scouts. In

terror and confusion the whites flew to the fort; and, while the men fought

bravely, the women held blankets to catch arrows and bullets, or bound up the

hurts of their defenders.

It was all over by daylight, and the red men sped away up the river, with

several prisoners, and such booty as they could plunder from the deserted

houses. Not till all fear of a return of their enemies was over, did the poor

people venture to leave the fort and seek their ruined homes. Then it was

discovered that Becky and the parson's children were gone, and great was the

bewailing, for the good man was much beloved by all his flock.

Suddenly the smothered voice of Becky was heard by a party of visitors, calling

dolefully:—

"I am here, betwixt the beds. Pull me out, neighbors, for I am half dead

with fright and smothering."

The old woman was quickly extricated from her hiding-place, and with much

energy declared that she had seen Onawandah, disguised with war-paint, among

the Indians, and that he had torn away the children from her arms before she

could fly from the house.

"He chose his time well, when they were defenceless, dear lambs! Spite of

all my warnings, master trusted him, and this is the thanks we get. Oh, my poor

master! How can I tell him this heavy news?"

There was no need to tell it; for, as Becky sat moaning and beating her breast

on the fireless hearth, and the sympathizing neighbors stood about her, the

sound of a horse's hoofs was heard, and the parson came down the hilly road

like one riding for his life. He had seen the smoke afar off, guessed the sad

truth, and hurried on, to find his home in ruins, and to learn by his first

glance at the faces around him that his children were gone.

When he had heard all there was to tell, he sat down upon his door-stone with

his head in his hands, praying for strength to bear a grief too deep for words.

The wounded and weary men tried to comfort him with hope, and the women wept

with him as they hugged their own babies closer to the hearts that ached for

the lost children. Suddenly a stir went through the mournful group, as

Onawandah came from the wood with a young deer upon his shoulders, and

amazement in his face as he saw the desolation before him. Dropping his burden,

he stood an instant looking with eyes that kindled fiercely; then he came

bounding toward them, undaunted by the hatred, suspicion, and surprise plainly written

on the countenances before him. He missed his playmates, and asked but one

question:—

"The boy, the little squaw,—where gone?"

His answer was a rough one, for the men seized him and poured forth the tale,

heaping reproaches upon him for such treachery and ingratitude. He bore it all

in proud silence till they pointed to the poor father, whose dumb sorrow was

more eloquent than

all their

wrath. Onawandah looked

at him, and the fire died out of his eyes as if quenched by the tears he would

not shed. Shaking off the hands that held him, he went to his good friend,

saying with passionate earnestness:—

"Onawandah is

not

traitor!

Onawandah remembers! Onawandah grateful! You believe?"

The poor parson looked up at him, and could not doubt his truth; for genuine

love and sorrow ennobled the dark face, and he had never known the boy to lie.

"I believe and trust you still, but others will not. Go, you are no longer

safe here, and I have no home to offer you," said the parson, sadly,

feeling that he cared for none, unless his children were restored to him.

"Onawandah has no fear. He goes; but he comes again to bring the boy, the

little squaw."

Few words, but they were so solemnly spoken that the most unbelieving were

impressed; for the youth laid one hand on the gray head bowed before him, and

lifted the other toward heaven, as if calling the Great Spirit to hear his vow.

A relenting murmur went through the crowd, but the boy paid no heed, as he

turned away, and with no arms but his hunting knife and bow, no food but such

as he could find, no guide but the sun by day, the stars by night, plunged into

the pathless forest and was gone.