Ali vs. Inoki (16 page)

Authors: Josh Gross

Gene LeBell poses with Antonio Inoki at a Cauliflower Alley Club event (photo used courtesy of Gene LeBell)

Antonio Inoki barely misses a kick to the face of Muhammad Ali (photo used courtesy of Bobby Razak and

The History of MMA)

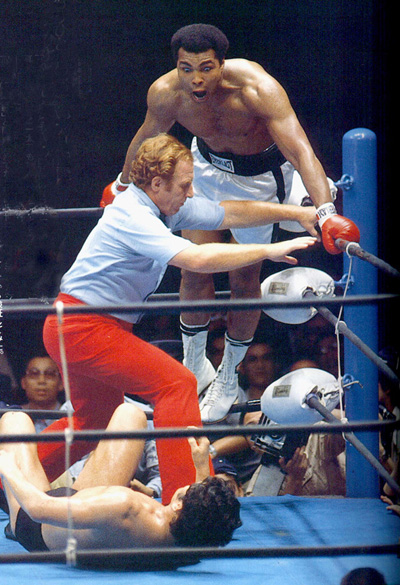

Referee Gene LeBell steps between Muhammad Ali and Antonio Inoki (photo used courtesy of Bobby Razak and

The History of MMA)

Muhammad Ali taunts Antonio Inoki as the Japanese wrestler asks the boxer to join him on the ground (photo used courtesy of Bobby Razak and

The History of MMA)

ROUND NINE

F

reddie Blassie changed Gene LeBell's life as much as anyone.

In his early twenties, LeBell fawned over motorcycles. Two to three times a week he took his Whizzer motorbike over to the Honda of Hollywood motorcycle dealership to hang out and daydream. He fantasized about what it would mean to have a new bike, even if he wasn't very good at riding yet. He told himself that he could beat everybody if he got his hands on a racing model with a high-backed fender. The problem was affording one.

Honda of Hollywood owner Bill Roberston Sr. enjoyed LeBell's company for obvious reasons, not the least of which was that “Judo” Gene paid him respect and was fun to be around. One day, as they often did, the pair made small talk and Robertson mentioned a customer who came into the dealership and wrote a bad check for $2,000. Robertson said the dealership tracked the customer down over the phone,

and he threatened that if anyone showed up at his place trying to collect he would kill them. Apparently he claimed he was from Chicago and a member of the mob.

LeBell relayed the story to Blassie, who loved playing a good angle when he could. Blassie came up with a concept to retrieve the cash, and “Judo” Gene went back to the dealership asking for the tough guy's address. Blassie wanted LeBell to show up on the gangster's doorstep holding a big box of matches claiming to be a pyromaniac. LeBell didn't know what that was and Blassie explained it was someone who liked to watch houses burn.

The house in question was located in Hollywood, near the Honda dealership just north of Santa Monica Blvd. LeBell showed up and got into character like Blassie would. As soon as the front door opened, the man inside tried to shut it on LeBell, who quickly blocked it with his foot.

“Mr. Robertson told me I could burn your house down,” LeBell said, adding a speech impediment. “I'm a pyromaniac.”

He shoved the door open and observed how nice the curtains were. “Oh, I'm happy,” LeBell muttered. The man asked what he wanted. “Bill says you're going to give me $2,000, but I'm going to burn your house down,” LeBell said as he spilled matches onto the floor.

The man quickly walked to the back of his house, reappearing with a thick wad of cash. He peeled off the balance of the debt, which went directly into the pyromaniac's pocket.

Returning to Honda of Hollywood, feeling good about himself, LeBell rolled out a beautiful motorcycle he had had his eye on. “At that age most guys were looking at women,” LeBell said. “I was looking at motorcycles, so you know

I was screwed up.” He wheeled the bike out and sat on it while waiting for Robertson Sr. to show himself. It wasn't long before the owner walked downstairs carrying a ballpeen hammer. Robertson asked if the customer had been paid a visit. LeBell gave the bike some gas then handed over $2,000, which sixty years later was worth roughly $17,500.

Robertson asked LeBell if he liked the motorcycle. Yes, of course. LeBell wanted it but he said he didn't have the scratch. The next thing LeBell remembers is Robertson caving in the metal gas tank with the hammer.

“Write it up,” Robertson told an employee. “It's his bike.”

One of LeBell's friends in the service department used a screwdriver to remove the big dent. “You couldn't even tell,” said LeBell, the new owner of a $320 machine, who was in heaven riding his first bike that “went really fast.”

LeBell has never been a wrenchâhe broke things not fixed themâso he threw a lot of work towards the Hollywood Honda folks. Plus he offered free towing, often taking a judo belt, his obi, to tie his bike off to another. Over the years LeBell's friendship with the Robertsons grew, and he referred more than a few customers their way. The dealership still offers a 10 percent discount on parts and service to anyone carrying a “Don't Fight It, Ride It” preferredcustomer discount card. The replica autographed card features a photo of LeBell corralling Ali in the heavyweight champion's corner during the Inoki fight.

Robertson Sr. took “Judo” Gene on flights with him aboard a single-engine Beechcraft Bonanza piloted out of Whiteman Airport in the San Fernando Valley. It was rare, but once in a while they flew as far south as Mexico. In

March of 1962, the same month Blassie dropped the WWA title to RikidÅzan at the Olympic Auditorium, Robertson Sr. made use of many hours logged over Baja California by navigating and copiloting a flight aiding a pair of motorcyclists, including his twenty-four-year-old son Bill Robertson Jr., on a first-of-its-kind 1,000-mile ride along the rugged Baja Peninsula. Telegrams were sent from the start and finish to document the thirty-nine-hour, fifty-six-minute trip. Honda went on to sell many bikes and the Mexico 1000 became a yearly tradition after 1967.

Robertson Sr. also helped inspire LeBell to become a successful stunt motorcycle rider. Already doing stunt work as a martial artist, LeBell added to his slate when productions began looking for riders who could get on a bike and lay it down or jump over obstacles if needed. It wasn't long before a third of LeBell's jobs were motorbike related. Soon he met the right folks and was approached with parts for character bits, leading to one of the most extensive résumés in Hollywood that continues to grow even as LeBell approaches his mid-eighties.

“Because of Freddie Blassie,” LeBell said, “that changed my life.”

When LeBell told Blassie the story of his pyromaniac adventure, the loud blond-haired wrestler loved every word, especially after hearing about the foot in the door. All Blassie wanted for LeBell was to remain in character, and accomplish the mission. The key for Blassie was simple: once a persona was created, never break that illusion.

LeBell obviously knew Blassie well and was mesmerized by his “Faces of Eve.” In 1957 Nunnally Johnson wrote, directed, and produced

The Three Faces of Eve

, an adaptation

of a book written by psychiatrists who identified dissociative identity disorder. Joanne Woodward won the Academy Award as best actress for portrayals of Eve White, Eve Black, and Jane. LeBell knew Blassie to be the sweetest guy or a wild man prone to “annihilate, mutilate, assassinate.” For his part, Blassie considered LeBell a close friend, a far cry from Aileen Eaton's other son Mike, who was widely disliked by wrestlers as he helmed the box office at the Olympic Auditorium and became a power player with the National Wrestling Alliance.

“It still amazes me that a guy like Gene LeBell could have a brother like Mike,” Blassie said in his 2003 book,

Listen,You Pencil Neck Geeks

. “There are times I'm sure one of them was adopted.”

As long as Blassie made Mike LeBell money, they didn't have any problems. Meanwhile, his relationship with Gene had nothing to do with business. They genuinely enjoyed being around one another, sharing a sophomoric sense of humor, a love of practical jokes, and a reverence for all things wrestling.

“Not only was [Gene] one of the top martial artists in the country, he trained with some of the most vicious wrestlers and shooters in the business,” Blassie said in his book. “When the family needed an enforcer to step in the ring with a wrestler who didn't want to go along with the program all they had to do was open Gene's bedroom door and tell him to get in his wrestling gear.”

Bearcat Wright became the first African American to hold a major pro wrestling title when he took the WWA heavyweight belt off Blassie in 1963. Wright bought into being champion, and though he was supposed to give up the

title in short order, that was the last thing he seemed to be willing to do. The wrestling power players at the Olympicâ the Eatons, booker Jules Strongbow, and Mike LeBellâ grew nervous that this six-foot-six, 270-pound guy with a legitimate boxing background didn't want to go along with the plan, so Gene was unleashed to stretch him. Blassie and LeBell confronted Wright in the Olympic Auditorium parking lot, right outside the door where the “locker room” interviews were conducted. LeBell moved as if he was going after Wright, who dropped the belt, got in his car, and wouldn't return to wrestle in L.A. until 1971.

In the early '60s, LeBell owned a boat with an inboard motor, a seven-foot dinghy really, that he liked to put in his swimming pool. One day LeBell and Blassie decided to take it with them to the beach. (Blassie, then a big-time television star in L.A., lived in Santa Monica and spent most afternoons tanning near the pier. He was ritualistic enough with his sun worship that some of his most ardent fans knew when and where they could find him on any given day.) Blassie brought a good-looking girl who couldn't swim and took her out in the boat even though there wasn't room for two. A wave turned the boat over and LeBell went running to retrieve it. “How about the girl?” LeBell yelled at Blassie. “She'll wash ashore,” replied the wrestler. She did. They drained the boat and got it and the girl back into the car, the end of her lone trip to the beach with the boys.

Such is the deviousness among wrestlers that there are different categories of pranks and cons. The most basic are called ribs. It could be as simple as twisting off the top of a salt shaker, or replacing a glass of beer with urine, or dropping a turd in a cowboy hat, but sometimes they were much

more involvedâand dangerous. Blassie was considered a hard ribber, but not the worst like the first WWWF champion Buddy Rogers or Johnny Valentine.

Valentine undertook a notorious set of ribs with and against Jay “The Alaskan” York that stand the test of time. One freezing winter night in Calgary, according to Roddy Piper's version of events, Valentine filled York's car full of water with a garden hose and let it freeze so in the morning the interior was perfect for ice hockey. Valentine, of course, was long gone by then. York took revenge the next time they ran into one another in Manhattan by finding an arc welder to angle iron Valentine's vehicle to street posts and parking meters.

York suffered from asthma and after matches always went right for his inhaler. Valentine knew this and decided that instead of inhaling medicine to open up his airways, York should draw in lighter fluid. After doing so, vomiting, passing out, and coming to his senses, York pulled a sawed-off shotgun on Valentine while his assailant was in the shower. Valentine looked at York and smiled. York blew a hole in Valentine's Halliburton aluminum briefcase. When people calmed down, Valentine went to his car. It wouldn't start. He opened the hood and saw that York, a demolition man in the Marines, had wired the car to explode but hadn't plugged it into the distributor. Instead, a fiendish note made it clear how close Valentine was to death.

A few weeks later in Minneapolis, Minn., the scene repeated itself. York walked into a dressing room packing a .357 Magnum as Valentine exited the shower. York spoke up and promised if Valentine messed with him again he'd die. Boom, the gun went off. Valentine went down, clutching his chest. The room froze. Most of the wrestlers packed heat

back then, and one of them, Harley Race, plainly told the wild-eyed York to put down the piece.

Race was about to shoot York when Valentine sprung to life. The blast had come from a blank, and blood was actually ketchup. As soon as the room realized what was underway, it sank in that this was just another classic rib.

Swerves are more involved than ribs. They typically emerge as part of a storyline presented to oblivious fans. The marks. Wrestling writers will also throw curveballs when smart fans, the snarks, think they know where a story is headed.

Most people assumed Ali's match with Inoki was going to be a work. That was the discussion behind the scenes and it went so far as Vince McMahon Sr. laying out the finish. The idea was to play off the sneaky Japanese stereotype, which is why Ali and Blassie both invoked Pearl Harbor in the lead-up to the match.

“The way Vince wrote it, Ali was supposed to come out and look like he was hitting Inoki with punches,” Bob Arum told

Sports Illustrated

in 2012. “Now wrestlers, they use razors to cut themselves so Inoki was supposed to cut himself, and blood would be everywhere. Then Ali would turn to the ref and say, âHey, please stop the fight.' Then Inoki would jump on Ali's back and pin him. Ali would get up and say this was just like Pearl Harbor, then we'd all go home.”

Before Ali met Inoki in Tokyo, while Vince McMahon Sr. promoted the WWWF closed-circuit locations in the U.S., his son, Vince McMahon Jr., was sent to Japan as an emissary. Junior presumed the AliâInoki contest would be worked, but soon realized that both sides of the bout had different plans.

Junior tells a story in which he attempts to persuade Ali to agree to stick with a scripted outcome. In Ali's hotel room, chairs and beds are pushed to the walls, making just enough space to wrestle. The story goes that McMahon took Ali down to the floor with ease, and made his case against participating in a legitimate fight.

“I certainly remember Vince being there and spending time around Ali,” said publicist Bob Goodman. “But wrestling Ali to the ground would have been a little strange to me.”

Publicly, of course, Blassie was all in for Ali. Privately he admitted rooting for the wrestler, though he disliked Inoki for several reasons, not the least of which was because to him Inoki had followed the path laid by RikidÅzan and jammed it down the throats of Japanese audiences. Blassie fully expected Inoki to twist Ali into a pretzel, but just in case the match went sideways, McMahon Jr. claimed a plan was concocted between himself, Blassie, and LeBell for everyone involved to save face.

In Blassie's 2003 biography, McMahon Jr., the promotional face of modern-day wrestling, laid out the scheme. According to the story, LeBell would sneak a blade with him into the ring. Some wrestlers were like surgeons with blades, and they could be very sneaky in terms of how it was used. As soon as there was any contact that made it look like Inoki was in trouble, LeBell was allegedly going to put himself in the middle of the combatants and figure out a way to knick Ali across the tip of his hairline. It wouldn't need to be a big cut, just large enough for sweat to take over and make it look bad.