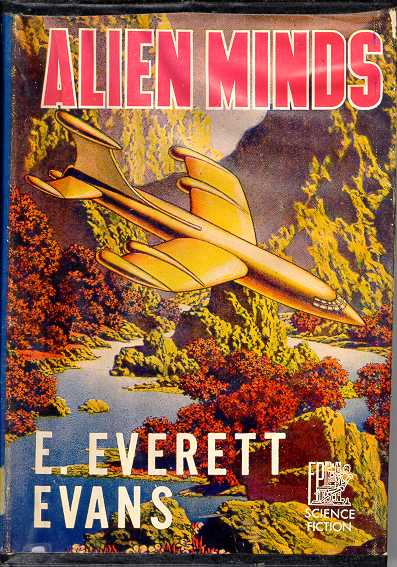

Alien Minds

by E. Everett Evans

Man of Many Minds

The Planet Mappers

Alien Minds

ALIEN

MINDS

E. Everett Evans

FANTASY PRESS, INC.

READING, PENNSYLVANIA

Copyright . . . 1955

by E. Everett Evans

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher.

FIRST EDITION

Printed in U. S. A.

For

Mother

to whom I owe so much

ALIEN MINDS

CHAPTER 1

WERE YOU LOOKING FOR A ROCH, NYER?" AN oily voice spoke up just by the elbow of George Hanlon. "I have some excellent ones here, sir."

"Yes, nyer, I want several, if I can find ones to suit me," the young man replied. Nor could anyone, glancing at him, know he was not a native of this planet, Szstruyyah, which the Inter-Stellar Corpsmen, in self-defense, called "Estrella." For the cosmetic-specialist who handled the secret servicemen's disguises had done a marvelous job in transforming the blond young Corpsman into an Estrellan native.

Hanlon continued looking into the outside cages con

taining these tailless ruches, the Estrellan equivalent of wild dogs. "I want eight, all as near the same size, coloring and age as possible."

"Eight, did you say?" the merchant looked at him in astonishment. Hanlon, carefully reading the surface of the man's mind, sensed the conflict there between the ethics his religion and philosophy had taught him, his natural love of haggling, and a desire to make as much profit as possible. But he could not sense the slightest suspicion that the man confronting him was not another Estrellan.

This was a great relief to Hanlon, for he was still afraid he might be recognized as a stranger and an alien. In his disguise he was still humanoid in shape, and still his

five feet eleven inches in height. But in addition to the ragged beard and longish hair, he had undergone outward structural differences that made him seem almost totally unhuman.

"That's right. Eight. I want them to be about two years old, in good health. Can you supply them?"

"I can if you can pay for them," the native looked somewhat questioningly at Hanlon's cheap clothing.

The young secret serviceman smiled, and jingled coins in his pocket. "I can pay."

"Then come with me, nyer, and we will find the ones you want."

Hanlon followed him inside the peculiar little open-faced stall that was one of the hundreds surrounding the great market square of this city of Stearra, largest on the West Continent of Estrella. His nose wrinkled against the stench of the uncleaned kennels.

The roches, seeing a stranger and, perhaps, being somewhat upset by his strange, alien effluvia, set up the peculiar, frenzied yelping that was their customary sound. To Han

lon, it was reminiscent of the wail of earthly coyotes.

The young Corpsman was on a very hair-trigger of caution and tenseness. Despite his splendid disguise, he had plodded through the crowd of the market place with a great deal of trepidation.

He had seemingly come through all right so far, and he began to relax a bit, yet was still somewhat fearful that he might give himself away by some difference of action, or speech, or by breaking one of their customs or taboos about which he knew all too little, despite his briefing and study before coming here.

"Have you decided which ones you want, nyer?" the proprietor asked, waving his hand toward the various cages, hardly able to believe he was to make such a large sale.

Hanlon said nothing, continuing to scan closely the roches, for his thoughts were still very much on this, his first prolonged venture into the streets and among the crowds of this strange new world to which he had been assigned fill his second problem.

His mind was constantly contacting others, for George Spencer Newton Hanlon was the only member of the secret service who was at all able to read minds. But he could read only their surface thoughts—and these Estrellans had such peculiar mental processes, so different from those of the humans with whom he was familiar, that they were almost non-understandable.

So he was still a bit hesitant to start the bickering he knew he must engage in to stay in character. To delay a bit further he continued examining the animals in the cages, not only with his eyes but mentally scanning the brain of each, that he might be sure of finding those in perfect health, with minds he could most easily control.

"Though how I can expect to find healthy ones in a filthy dump like this, I don't know," he thought. But he finally did.

While he was doing this, however, he was reminded of the time he had discovered this ability to "read" animal minds, and how his subsequent studies had enabled him to control their minds and bodily actions with amazing skill. It was this ability that had led him to this market place on his unusual quest.

"I'll take that one, and that, and that," he said at last, pointing out, one after another, the eight animals he wanted.

"Yes, nyer, yes," the puzzled but delighted proprietor said, as he transferred the indicated animals to a single, large cage. "That will cost you . . .", he eyed Hanlon carefully to see if he could get away with an exorbitant price. Something seemed to tell him the stranger did not know just

how much roches customarily sold for, and he decided to raise his asking price considerably. ". . . they will be seven silver pentas each, nyer, and believe me, you are getting a fine price. I usually get ten each,"—he was lucky to get two, Hanlon read in his mind—"but since this is such a large sale I can afford to make you a bargain."

Hanlon grinned to himself as he computed quickly. Five iron pentas, he knew, made one copper penta, five coppers one tin penta, five of these one silver penta, and five silvers a gold one. This made the silver piece worth about one-half a Federation credit. The price seemed ridi

culously low, even with this big mark-up. Hanlon would willingly have paid it, but he had learned from the briefing tapes, and again now from his reading of this merchant's mind, that they loved to haggle over their sales—made a sort of game of it—so he turned away, registering disgust.

"A fool you think me, perhaps," he said witheringly. "Seven silver pentas, indeed. One would be a great price for such ill-fed, scrawny, pitiable animals as those."

The merchant raised his hands and voice in simulated rage—which did not prevent him from running around to face Hanlon's retreating figure, and bar his way. "'Robber', he calls me, then tries to rob me in turn. Six?" he suggested hopefully.

Hanlon was now enjoying the game, and threw himself into it with vigor. "I call on Zappa to witness that you are, indeed, the worst thief unhung," he also spoke loudly, angrily, largely for the benefit of the crowd of natives that was swiftly gathering to watch and listen to this sport. "Look, that one is crooked of leg, this one's hair is ready to fall out, that one is fifteen years old if a day. I'll give you two."

Yet he knew all the animals were in perfect health, and all about two years old. He had carefully selected only such.

"I ask anyone here," the seller wailed as he waved toward the crowd that was watching and listening with huge enjoyment, "I ask anyone here who knows roches to examine these you have chosen. They are all exceptional, all perfect. The best in my shop. Five and a half."

Hanlon turned away again. "I'll go find an honest dealer," he started to push through the crowd, but the merchant hurried after him and grasped his smock. "Wait, nyer, wait. It breaks my heart to do this. I'll lose a month's profit, but I'll sell them to you for five pentas each. To my best friend I wouldn't give a better price."

"That shows why you have no friends. Three even, take it or leave it," Hanlon was still pretending indifference.

"I'm ruined; I'll be forced out of business," the dealer screamed. "They cost me more than that. Oh, why did I rise this morning. Give me four?"

Hanlon grinned and dug out a handful of the penta

gonal-shaped gold and silver pieces. He counted into the merchant's quivering but dirty hands the agreed-upon thirty-two pentas.

The native looked at them, wordlessly, but his face was a battleground of mixed emotions. Finally he reluctantly counted out half of them into his other hand, and held them out to Hanlon. "No, nyer, I cannot over-charge you. Two is the price."

"You're an honest man after all, and I apologize," Han

lon said, smiling, as he pushed back the outstretched hand. "Those I chose are fine animals, perfect, and the best in your shop. So keep the money. Send them to my room this midday," he commanded. "It's on the street of the Seven Moons, at the corner of the street of the Limping Caval the house painted pink in front. Second floor to the rear. My name—Gor Anlo—is on the door."

He had taken that name on this planet since it most nearly corresponded to his own from among the common Estrellan names.

The rock-dealer, well pleased with the outcome, bobbed obsequiously. "It shall be done as you say, nyer, and I shall include feeding and drinking dishes. What about food for them?"

"That's right, they'll need dishes, and thank you. Let's see your meat." But after examining the poor quality food the merchant displayed, he would not buy.

"I'll get something elsewhere, if this is the best you have," Hanlon told the man with a disarming smile. "Such fine roches deserve the best."

"Yes, my food is poor," the dealer moved his hand deprecatingly. "I'm glad the roches are to have such a con

siderate master."

And Hanlon could read in his mind that the merchant actually was pleased. The SS man felt that he had passed this first public test with high grades.

In one of the better-class food stalls Hanlon found sonic good, clean meat, and the other foods such animals ate. After the customary game of haggling, he ordered a two days' supply to be delivered at once, and the order duplicated every other day until further notice.

Then he hunted up a suit-maker. Here it took a lot of persuasion, and the showing of his money, before the tailor would even believe that Hanlon really meant what he said when he tried to order nine uniforms, eight of them of such outlandish shape and size. For one of them was for himself, the others for his newly-bought roches.

It was only when Hanlon finally lost patience and said sharply, "You stupid lout, I want them for a theatrical act," that the uniform-maker realized the reason for such an un

usual order. Then things ran smoothly. The design was sketched, and material of a red to harmonize with the grayish-tan of the roches was chosen. The tailor consented also, for an added fee, to rush the job.

Hanlon's way home led through part of the district where the larger, better-class shops were located. He stopped in front of one of these.

He knew from his studies and from what he had seen here, that Estrella was just at the beginning of a mechanical culture. What sciences and machines they had were unbelievably crude and primitive to him, accustomed as he was to the high technologies of Terra and the colonized planets.

This display he was scanning featured their means of personal transportation. There were, of course, no moving slideways, nor even automobiles nor ground cabs nor copters. Instead, the Estrellans used motorized tricycles. Even the smallest of these was heavy, cumbersome, crude and inef

ficient, but they were speedier and easier than walking—when they worked.

The tricycles had large wheels, about three feet in diameter, with semi-hard, rubber-like tires. There were two wheels in back and one in front, steered by a tiller lever. Because of the weight of the engine and tank for the gas, even the smallest trike weighed several hundred pounds.

The fuel was acetylene gas, Hanlon found to his dismay. Electricity had been discovered here, but as yet they knew only direct current. No AC—no vacuum tubes—no tele

phones—no radios—no television—"ner nothing," Hanlon snorted in disgust.