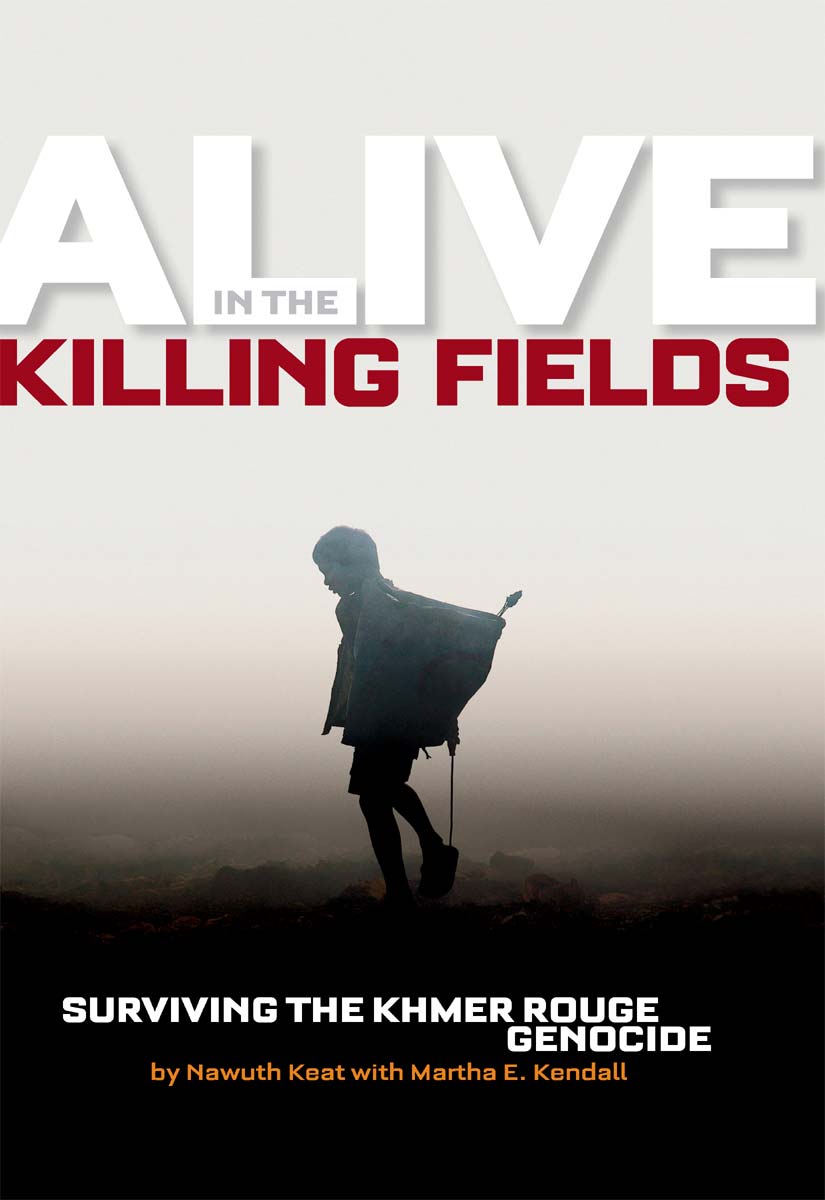

Alive in the Killing Fields

Read Alive in the Killing Fields Online

Authors: Nawuth Keat

Copyright © 2009 Nawuth Keat with Martha E. Kendall

Published by the National Geographic Society.

All rights reserved. Reproduction of the whole or any part of the contents without written permission from the National Geographic Society is strictly prohibited.

The publisher would like to thank Kim DePaul, Executive Director of the Dith Pran Holocaust Awareness Project for her generous assistance and thoughtful review of this book.

For rights or permissions inquires, please contact National Geographic Books Subsidiary Rights: [email protected].

Cover design by Jonathan Halling. Interior design by Sandi Owatverot.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Keat, Nawuth, 1964-

Alive in the killing fields: surviving the Khmer Rouge genocide /by Nawuth Keat and Martha E. Kendall.—1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN: 978-1-4263-0666-2

1. Keat, Nawuth, 1964—Juvenile literature. 2. Political refugees—Cambodia-Biography. 3. Political refugees—United States—Biography. I. Kendall, Martha. II. Title.

DS554.83.K43A3 2009

959.604’2—dc22

[B]

2008039805

09/WOR/1

This book is dedicated to the men, women, and children who lost their lives under the Khmer Rouge.

-N.K. and M.E.K.

I want to thank my teacher and friend, Martha Kendall, for offering to write my story down.

—

Nawuth Keat

I would like to acknowledge the loving support of my family, the fine work of National Geographic editor Priyanka Lamichhane, and especially the courage of Nawuth Keat who re-lived the tragedies recounted in this book as he told them to me.

—

Martha E. Kendall

Nawuth (NAH-wooth) Keat

was a student in my World Literature course at San Jose City College. He seldom spoke in class. So I was surprised on the last day when he said, “I’d like to share my story with you.”

Nawuth described his childhood in war-torn Cambodia, his family’s tragedies, the constant hunger, and his dangerous escape. I looked around the classroom and saw that I was not the only listener who had been moved to tears.

“Nawuth, would you like me to write your story down for you?” I asked.

“Yes,” he answered simply.

Since then Nawuth and I have spent many hours working together. His English is rough. My role is to gather his memories and write them down clearly in English. The words are mine, but the story is his.

Sometimes the going got tough. As Nawuth reviewed the manuscript, he was taken back to his painful past.

I asked, “Are you sure you want to continue with this project?”

“I want people to know the truth about what happened,” he said.

Here is Nawuth’s truth.

MARTHA E. KENDALL

“YOU’RE LUCKY”

Gunshots!

I bolted awake. My parents yelled, and we all jumped from our beds. The dogs barked.

“We have to get out of here!” my parents said.

Still in our pajamas, we darted outside.

“Run to my mother’s,” my father said. She lived next door, and we hurried to her house. We heard gunfire close by, right in the neighborhood.

We got our grandmother, and together all ran toward an old rice barn across the street. But the gunshots came so close to us that we couldn’t make it to the barn. Instead, we dove into a ditch—my mother, the baby, my grandmother, my younger brothers, my aunt and uncle, our babysitter, and me. I was nine years old.

The ditch was too shallow to hide us, but in the darkness, I hoped we’d be overlooked. My father ducked behind some bamboo about a hundred feet away.

My heart pounded. I heard screams, explosions, howling animals, and the fiery roar of grass-roofed houses burning.

My mother had always told us, “The Khmer Rouge (Kuh-mair Roozh) might come at any time to raid our village. Their leader, a man named Pol Pot, says he and the Communists want to make everyone in Cambodia equal, but that’s just talk. It is an excuse they use to help them gain power. Banding together in big gangs, they kill people and steal money, gold jewelry, and guns.”

Now they had come: the Khmer Rouge, the Red People. They were mostly poor and uneducated peasants, thieves, drunks, and fugitives.

My mother was so afraid of them; she rarely let us sleep at home. Most nights my father took us to the home of my mother’s parents, about five miles away. To get there, they drove motorcycles, pulling us kids in trailers behind them. My mother said, “It’s safer there, because it’s a larger town.” But on this night we had stayed home to prepare food for the next day’s holiday feast, the Cambodian Thanksgiving.

Our town had no electricity, so the Khmer Rouge tried to light up the street by starting fires anywhere they could. They threw burning matches into our house, but it did not ignite. Then they used a trick to fool anyone who was hiding in the shadows. They yelled in no particular direction, “Hey, you, stand still! If you move, we’ll shoot!”

My grandmother fell for it. Terrified, afraid the family had been seen, she cried out, “Please don’t shoot. We have done nothing. These are innocent children.”

A Khmer Rouge ran to the ditch where we huddled.

My grandmother begged, “Take our gold and money. Please just leave us alone.”

Then my uncle stood up. The Khmer Rouge demanded, “Where’s the gun you bought last week?”

My uncle told him the truth, “I didn’t buy any gun.”

The Khmer Rouge raised his M-16 rifle and shot my uncle in the chest. Fired from that close range, the bullet careened through my uncle’s body, and blood spewed out behind him. He fell dead on the ground.

My grandmother screamed. “Don’t kill us,” she begged. The killer sprayed her with bullets, and the rest of my family, too.

An M-16 bullet makes a small hole when it enters a human body. After it tears its way through the flesh, it exits, leaving a gaping hole the size of a fist.

I was shot three times. I lay limp in the ditch. It was filled with my family’s blood. When a Khmer Rouge kicked my head one way, I let my head flop. He kicked it the opposite way, and I let it flop again. “If he knows I’m still alive,” I thought, “he’ll shoot me.” Another Khmer Rouge kicked me again. They must have thought I was dead, so they didn’t waste another bullet on me. A few minutes later, they were gone.

My youngest brother, barely five years old, was crying, and I tried to calm him. Hackly said nothing. He looked like he was in shock. My mother had held my little sister to her breast, hoping to keep her quiet as we squatted in the ditch. Now they were both silent. A single bullet pierced my little sister and then my mother’s heart. With

my right hand, I felt my baby sister’s face. I found only a hole where her cheek should have been.

My mother was dead. My baby sister was dead. My grandmother was dead. My aunt and uncle were dead. My babysitter was dead.

I tried to get up, but my legs wouldn’t work. I kept falling down into the bloody ditch. My left arm was so swollen I couldn’t bend it. Two bullets had hit my elbow. Another had torn through my left hip.

My father heard the slaughter from his hiding place. Helpless, he stood in the dark, unable to see where to aim his gun or throw a grenade without killing us. He never told me what went through his mind that night. I never asked.

When the Khmer Rouge ran through the village, they had tossed grenades and burning matches at the houses. One of the grenades exploded inside a house near ours, killing all but one young boy, whose body was covered with shrapnel. Someone with a trailer behind his motorcycle took that boy and me to get medical help. Dad stayed at the scene of the massacre, trying to deal with the chaos that had just struck. On the way to the hospital, the boy next to me died.

My country is poor. At the hospital, there were no beds or good medicines. I lay on a piece of metal. The doctor told me, “You’re lucky. If the bullet had hit an inch closer to your abdomen, your liver would have been destroyed.”

I flinched when his assistant dabbed at the dried splotches of blood—my family’s and my own—that covered

me from my face to my feet. My arm hurt so much. I was scared, and I was alone. Then the doctor treated my bullet wounds. When he stitched them, with no painkiller, I cried, and then I screamed until I passed out.

The doctor later told me, “I did my best to put your smashed elbow back together. I made the cast hold your arm in a slightly bent position, so the elbow will set in a natural-looking angle. But I’m sorry, it will never flex normally again.”

The bullet wounds slowly began to heal, but my misery was just beginning.

FROM STUDENT TO SLAVE

I was born in Cambodia in 1964,

the fifth of eight children. In those days, most families were big. My brothers and sisters and I were each about a year and a half apart. I had two older sisters, Chanya and Chantha, and two older brothers, Lee and Bunna (pronounced “BOOna”). My younger brothers were Hackly and Chanty, and our baby sister was Chantu. But we hardly ever used our formal names. Instead of calling me by my real name, Bunpah, everybody used my nickname “Mop” which meant “healthy baby.”

My father was a successful rice farmer, one of the most prosperous in our little village of Salatrave. Most people lived in small, grass-roofed huts, but our two-story house was made of brick, and it had a tile roof. My father had built it on a large lot on the highest ground in the town. That location was important because it ensured that our house did not flood during the rainy season. We also had a tractor and a motorcycle, much more than other families owned. Our prosperity probably put us in extra danger from the Khmer Rouge. My father hired seasonal help during the rice harvest, and he also had one full-time

worker who drove our tractor. That employee, named Zhen, often came to work drunk, and my father warned him he had to stop drinking. Zhen didn’t change, so my father fired him. He ran away and joined the Khmer Rouge. With them, Zhen didn’t have to worry about trying to make an honest living. Instead, he could get money by robbing and killing other people.

I do not know if Zhen encouraged the Khmer Rouge to target my family on that terrible night in 1973. But whether a family was singled out or not, no one was safe.

My older brothers and sister Chantha lived in the city of Battambang (BAHT-am-bong), and my oldest sister Chanya lived in the city of Pursat (Pa-SAHT). If they had been with us when the Khmer Rouge attacked, they might have been murdered too.

“Mop,” my father said to me, “I’m going to send Hackly and Chanty to stay with Chantha where they will be safer.”

“What about me?”

“I will take you to Pursat to live with Chanya. She can take care of you until your wounds heal. Then you can join Chantha and your little brothers in Battambang.”

Cambodian children are very polite. I didn’t question why he made his decisions. But I did ask, “Dad, what are you going to do?”

“I’ll keep the farm going,” he said.

I still couldn’t understand what I had just experienced. It was too awful to be true. No matter how much my wounds hurt, my heart hurt even more.

How could my mother be dead? And my baby sister? My grandparents, too, and my uncle and aunt? It didn’t seem real. And now my father was sending me away.

Chanya, her husband, and their baby welcomed me into their home in Pursat, which is about 10 miles (16 km) southeast of Salatrave, but I didn’t feel happy to be there. I didn’t feel happy about anything. But as the days and weeks passed, a routine developed. Thanks to Chanya’s husband being a police officer, he had many professional friends. One of them was a doctor who came to the house to give me shots a couple of times a week to help prevent infection. He changed the dressing on my wounds and put my arm in a sling.

Chanya was kind to take me in, but she did not have my mother’s sweet temperament. When we were kids all living at home, as the oldest one, she used to boss us younger kids around. Sometimes she spanked me. During the months I stayed with her in Pursat, she was very strict, and she yelled at me a lot. In the mornings, my gunshot wounds ached the most, but Chanya never let me stay in bed. If I said my arm hurt, she still made me get up early and drag myself to school.

I was glad when my wounds healed enough that I could go to Battambang. When my father picked me up from Chanya’s, he said I was to help Chantha with my younger brothers. Chantha and I had always gotten along well. She was about four years older than I was, and she had a kind, gentle nature. She never complained or got mad. She was an excellent student, too.

I was already familiar with Battambang, which is about 12 miles (19 km) northwest of Salatrave. Before the Khmer Rouge came, I spent weekdays in Battambang going to school. That is because Salatrave was so small that it did not have a good school. Battambang was large, second in size only to the capital, Phnom Penh. After I finished kindergarten in Salatrave, my parents sent me to Battambang to study. My older brothers Lee and Bunna preferred to stay home and work on the farm, but my parents encouraged me to go to school. Chantha went, too. We lived in Battambang during the week with my uncle and his family. Every day I went to public elementary school. Then, after school let out in the late afternoon, I attended a private school for a couple of hours. I was allowed to go for free because the teacher was a friend of my father, and I was a good student. I saw kids who were not as fortunate as I hanging around the classroom door, eager to hear any wisdom the teacher might give. It was a privilege to be allowed a seat inside. The girls sat on one side of the classroom, the boys on the other. We were proud of our uniforms. We understood that education was important, and we worked hard. On Friday night, I would take the bus, which was like a small mini-van, back to Salatrave.

When the Khmer Rouge took over, everything changed. My uncle’s family left Battambang, so my sister, Chantha, along with my brother Bunna, found a new place to live. Lee was staying by himself in Pursat.

When I moved in with Bunna and Chantha, Chantha tried to be a mother to my little brothers and me, but she was barely fifteen years old herself. She was busy with her own regular studies, and she spent a lot of time at her after-school classes. She was taking classes to help her prepare for a very hard exam that would determine whether she would be admitted to college. A smart man named Van Lan taught the prep classes. He was a few years older than Chantha, and he had been to college. Chantha liked studying with him.

I tried to concentrate on my schoolwork, but it was hard not to think about what had happened to my family. It made me especially sad to think of my mother, so I tried not to remember the terrible murders I’d witnessed. The best way to avoid the pain was to recite to myself, “Do not think about it. Do not think about it.” But sometimes I couldn’t help it. So when I thought about the past, I tried to focus on the good parts of our life before the Khmer Rouge came.

I remembered the fun of waiting for my mother’s bus to come back to Salatrave from Battambang where she went for her weekly shopping trips. She always brought us candy and cookies. One time she brought me a special surprise—brand new plastic flip-flop sandals. I often went barefoot, so I was really excited. I loved those sandals.

We grew most of our own food, and my mother’s weekly trips to Battambang supplied us with anything else we needed. But now and then my mother would send me to a house in the village to pick up something

between her shopping trips. There were no stores. Everyone knew that certain items could be purchased from certain people, like pain pills from one family, or sugar or salt from others. If we wanted a snack, we could pick fruit from the trees. I especially liked guavas, which grew everywhere.

Every day my mother made us take a bath, but we didn’t use bathtubs. Nobody had running water at home. If we needed fresh water, it had to be carried from the well in the center of town. We took a big clay pot with us. Because it is so hot in Cambodia, the water was always warm. To bathe, my friends or brothers and I took turns pouring pots full of water over each other. Because nobody had shampoo, we washed our hair just like we washed our body, under the spray of poured water. Chantha used clippers to trim my brothers’ and my hair really close to our heads. We looked alike, bigger or smaller versions of each other depending on our ages.

We didn’t have toilets, either. We used an outhouse. When I was little, I was always scared to go there by myself at night. Because there was no electricity, it was dark. Even though the outhouse was only 50 feet (15 m) away, the walk to it seemed much longer because in my imagination, giant monsters were hiding, waiting to get me.

We didn’t always have to get the water from the well ourselves. My family could afford to hire teenagers to help us around the house. I was glad, because they did some of the chores, like getting the well water, washing

clothes, sweeping the wooden floors in the house, and weeding our garden. In exchange for their work, my mom gave them food to take home to their families. Even with their help, my mom still had a lot of hard work to do. I remember her starting the cooking fire every day. She prepared the food over the flames, and the charcoal made our house really smoky. She was always rubbing her eyes, and mine stung, too.

Sometimes my mother would ask me to go with her to the rice field; “Mop, do you think you can walk all the way to the field with me? I want to re-seed a few sections.”

“Yes, please, please, please!” I’d say.

What an adventure those special days were. For me, it was a rare treat to walk that far away from the house and to spend a whole day outside with my mother. I especially remember the fun I had on one of those trips during the rainy season. If I close my eyes, I can re-live the scene. I smelled the fresh moist air of the fields. The humidity made my skin feel extra soft. While Mom did the planting, I played in the mud nearby. I thought she would scold me for getting dirty, but she didn’t. With my fingers and toes, I made patterns in the wet dirt. Then I collected rocks and arranged them in three piles, targets for clods of mud that I tossed at them. I backed farther and farther away, trying to improve my accuracy. Lots of times I flung the mud balls so hard that they fell apart even before they landed. When I hit the farthest target, I laughed. I’m good! When I felt too hot to stay in the sun any longer, I moved to the shade and wondered what to

do. Then a bright green bird swooped in front of me. It was a bee-eater, a common sight in Salatrave. I wondered, “What would it be like to eat a bee? Wouldn’t it sting you? And what would it be like to fly?” I pretended I could fly. I stretched out my arms and squawked at every bug I saw. Then I decided I’d eat some insects—but no bees—just to see what they tasted like. I caught a silver-colored insect with my hands, but its sparkly wings looked pretty and delicate. I didn’t want to destroy them, so I opened my hand and let it go.

Mom said, “Mop, I’m done for the day. Let’s walk back.”

As we walked, I noticed tall wading birds in a rice field. They had red faces and long yellow legs. “What are those?,” I asked.

“They’re called lapwings,” she said. “Some people say those birds sleep on their backs at night and stretch their long legs out straight to hold up the sky.”

“Do you think that’s true?” I asked.

“No,” she said and laughed. “It’s just a superstition.”

“I don’t believe it either,” I said.

It seemed to me we walked a long ways. By the time we reached our house, I felt very worldly and important. When I got into bed that night, I raised my legs up toward the ceiling. I was glad I didn’t have to do that all night long.

My mother was kind, but she made me behave, too. She scolded me when I got mad at my brothers. I hated their teasing me whenever our neighboor Deenah and

her family stopped by to visit. I chased after them when they yelled, “Mop, here comes your wife!” Of course Deenah was not really my wife, but our marriage had been arranged. Nobody else in my family had an arranged marriage, but our mothers decided to arrange a marriage between Deenah and me because of a strange dream they each had. Just before Deenah and I were born, a couple that lived nearby passed away. Deenah’s mother and my mother had an identical dream that the couple wanted to live with them. The mothers were so surprised by this that they decided their babies must have a special connection. This led to my mother’s decision to name me “Bunpah.” She thought the name seemed very grownup, in anticipation of my marriage. I never liked that name because the last thing I wanted to think about was getting married. Like most kids, I wanted to think about playing and having fun. Deenah was nice, but I was too young to care about girls.

My older brother Bunna and I often got scolded for arguing. I remember one time I knew I was going to be in trouble. To get away from my mother, I scrambled up a coconut palm as high as I could go. My mother came looking for me, and when she saw me up there, she was scared I would fall down and be killed. She went away so that I would come down before I got so tired that I would fall out of the tree. When I came down unhurt she was so relieved that she did not even punish me.

My friends and I made up simple games. We played with rubber bands and marbles. Any piece of litter on the

street could become a toy. We did not have organized teams or ball games. My good friend, Whee, lived next door. Sometimes he would come sleep over at my house, and sometimes I would go to his. We laughed a lot. He was older than me. In the Cambodian language, younger people usually speak more politely to older people. But we agreed to treat each other as equals. After the Khmer Rouge came, everything changed. I don’t know what happened to Whee’s family.

Now that I was living in Battambang with Chantha, I missed Salatrave, and especially my father. The Khmer Rouge had burned down most of our village, but every weekend I still liked to go there. Chantha and my brothers stayed in Battambang, and I took a taxi to see Dad. A taxi was a trailer pulled behind a motorcycle. The ride was scary, and even though Bunna was older than me, he was too timid to make the trip. I was scared, too, but I went anyway. I felt less nervous after my father arranged to have the same taxi take me each week. Even though the Khmer Rouge had blown up half of our house, Dad still lived there. He raised chickens, grew rice, and kept a big vegetable garden.

At the end of one of my visits to see Dad he said, “You’re a good boy, Mop. Take this rice and these eggs, and vegetables. If there is any left over, tell Chantha to give the extra to anyone who needs it.” Then he loaded the food next to me in the taxi trailer. As the taxi pulled away, I looked back and saw him standing alone in front of our ruined house. I tried to smile at him, but I couldn’t.

He had told me I was a good boy. He usually did not talk much, and I was not accustomed to being praised. I wasn’t sure if I was good or not. I was sure that I hated to leave him, but I had learned not to cry.